4.2 The force-multiplier argument

The humanitarian position described in Section 4.1 is that people should always have priority over heritage. A simple understanding of this is that human lives should never be sacrificed, or even put in danger, to protect heritage.

Yet, protecting heritage can sometimes provide powerful instrumental military benefits for human beings. For instance, if a military force is occupying or at war in another country:

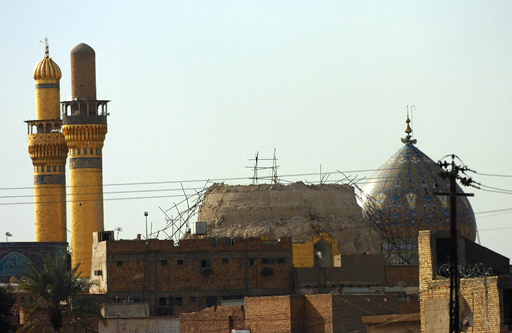

- Protecting heritage could provide a psychological boost to the local population. Allowing it to be damaged could cause disruption, anxiety and, in the worst cases, an increase in violence among communities. For instance, in 2006, the bombing of the Al-Askari Mosque in Iraq led to a significant increase in aggressive reprisals and deaths (Figure 11).

- Protecting heritage could also benefit the relationship between civilians and the military. If the conflict causes damage to treasured monuments or sites, the local population may become hostile. Alternatively, a force which prevents such damage conveys a respect for the people and may succeed in winning their hearts and minds.

- Defending important monuments and buildings may also provide a morale boost for the troops themselves, as well as their supporters in their home countries.

- Finally, heritage can be important for post-conflict peace-building. It may be instrumental in re-forming broken communal identities. It can also provide an economic boost to their recovery through added tourism and employment.

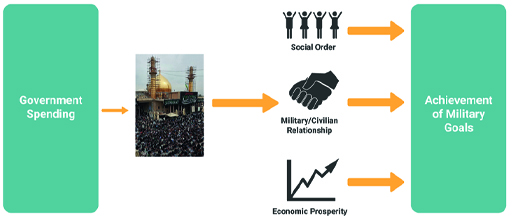

These kinds of benefit are called ‘force-multipliers’ in the military – factors which make military goals easier to accomplish (Figure 12). All of the force-multiplier benefits mentioned mean that saving cultural heritage can have a positive impact on limiting and avoiding human suffering and even deaths. Where the benefits of heritage are present, wars could potentially be ended sooner and with less bloodshed.

Therefore, even if we believe human beings are always more important than heritage, sometimes our goals are going to be best served by actions which superficially appear to put heritage first. For example, you may risk ten soldiers’ lives by telling them to guard a religious site. But if you predict the site’s destruction would cause an eruption of aggression and fighting, and perhaps a hundred extra deaths, then protecting the site appears to be the best course of action.

This force-multiplier argument parallels the economic justification for rebuilding Notre-Dame mentioned in Week 1, Section 2.3. Both arguments hang on the observation that sometimes, if we want to help human beings, the best thing we can do is to protect heritage and the benefits it provides. In the case of Notre-Dame, the benefits were primarily economic and political. In these force-multiplier cases, the benefits are primarily the avoidance of future violence and social disorder.

If either of these economic or force-multiplier benefits are sufficiently weighty, they can sometimes justify the imposition of a lesser risk of harm to human beings in order to secure those benefits. Whether we are talking about spending money on a restoration project or putting soldiers in harm’s way to avoid damage to an ancient temple, these smaller human costs can sometimes be worth paying to receive an even more valuable humanitarian result.