4.2 Ocean acidification

Another less well-known environmental impact is also affecting our oceans. It is not climate change, although it shares its main cause. It is a critical issue in considering geoengineering design.

The ocean has absorbed about 30% of the carbon dioxide humans have emitted into the atmosphere. When carbon dioxide dissolves in water it forms a weak acid called carbonic acid. The net effect of this is to increase the relative acidity of the water.

This decrease in pH is known as ocean acidification. Note that this does not mean the ocean is now acidic. The surface of the ocean is alkaline, so the pH decreases towards the less alkaline part of the scale (in the same way that a temperature increase from −7°C to −5°C is a warming). The IPCC estimates that ocean mean pH decreased from about 8.2 to about 8.1 for the period 1765–1994. In the Southern Ocean around Antarctica, pH changes are estimated to be larger than the global mean.

Why does it matter whether the ocean pH changes?

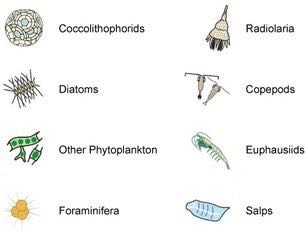

Calcifying marine organisms such as planktonic foraminifera (Figure 14) are adapted to the chemistry of the water around them to make their shells. Ocean acidification makes it more difficult for these organisms to precipitate the carbonate. The IPCC assess that the shells of foraminifera in southern oceans have reduced in thickness due to ocean acidification (IPCC, 2014).

Foraminifera are not quite as appealing as polar bears as an icon of human impacts on the environment. But calcifying organisms like these lie at the base of many marine food chains.