1.1 What about ethnicity?

Because race has been discredited as a scientific categorisation of human differences and has such a violent legacy, the terms ‘ethnicity’ and ‘ethnic groups’ have become more widely used. Although ethnicity and race mean different things, they remain tangled together. The key difference is that ethnicity is not a hierarchical concept. It avoids the issues of purity and superiority bound up in the idea and history of race. Ethnicity refers to the collection of cultural, historical, physiological, religious, linguistic, national, regional and local characteristics that bind people into groups who share various features of those characteristics. It is a looser and less rigid concept, and from it comes the related concept of ‘ethnic diversity’.

Everyone has a past and places in the world that shape their life and their prospects. The concept of multiple ethnicities and ethnic diversity is an attempt to come to terms with these inevitable differences in human life but they still remain ‘labels’ that tend to be fixed by the powerful on the less powerful. Because recording ethnic identity is a feature of youth justice practice, this first activity invites you to reflect on these issues.

Activity 1 Ethnicity or race: it’s not black or white

How do you describe your ethnicity?

Who asks you to describe your ethnicity?

What words work in describing ethnicity?

Discussion

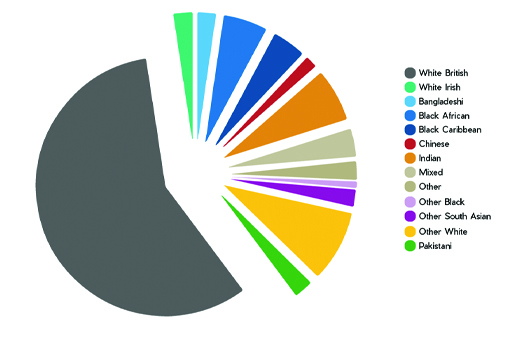

You probably don’t introduce friends or workmates to anyone by describing their ethnicity and the usual reasons for defining your ethnicity are to do with official procedures. One of the most common ways to refer to your ethnicity is to use the UK Government census categories. The 1991 census was the first to record ethnicity and it used nine categories: ‘White’, ‘Black–Caribbean’, ‘Black–African’, ‘Black–Other’, ‘Indian’, ‘Pakistani’, ‘Bangladeshi’, ‘Chinese’ and ‘Any other ethnic group – please describe’. By 2011 this had expanded to eighteen categories. The words used are a telling mixture of nations, colours, regions and countries.

Ethnicity, unlike race, is not meant to be fixed but fluid. This makes recording it a bit more complicated. For instance, in the 1991 census you might have been categorised as ‘White’, but by 2001 will have become ‘White–Irish’.

It is easy to get bogged down in the differences and intricacies of ethnicity and to forget that often it is a power struggle that decides who is doing the counting and categorising, what is counted and what it is counted for. For children and young people, it can be through schools or health services that they become aware of an official ethnic category. For some, it is the police who these young people find recording their ethnicity and insisting on the significance of the words used to describe their sense of belonging or their identity. Since the 1970s the police have used the 6+1 IC (Identity Codes) formula to describe the perceived or apparent ethnicity of suspects or other people they interact with. The 6+1 IC formula comprises the following categories that are not recognised ethnicities but are used as provisional features of identification:

- IC1 White Nordic – north European

- IC2 ‘White south European’

- IC3 ‘Black’ – Sub-Saharan African or African-Caribbean

- IC4 ‘Asian’

- IC5 ‘Oriental’

- IC6 ‘Arabic’

- IC9 Unknown

Now you have spent a bit time and effort exploring these fundamental background issues, it’s time to move into the youth justice system itself.