1 Why social and economic justice?

The first of the four principles you will look at is ‘social and economic justice for youth justice’.

There are youth justice systems in most structures of government and all the countries of Europe have distinctive responses to young people’s offending behaviour. Each of the four jurisdictions of the UK has developed approaches that reflect their history and contemporary ideas about children, crime and punishment.

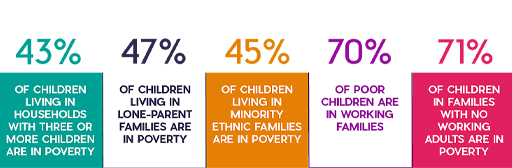

Many people involved in these systems – the people who work in youth courts, Children’s Hearings panels or Restorative Conferences – would tell you that the children they see most frequently are the children of people who are poor, and who are poor themselves. This is consistent with research evidence that correlates the identification of offending behaviour with high rates of child poverty, social and economic marginality and other forms of social hardship (Muncie, 2014; Yates, 2010). Those children and young people who attract intervention from the police are mostly located in neighbourhoods and communities worn thin by poverty.

Families and children under the pressures of limited domestic space and scarce social or financial resources are often let down by education and other services. Youth justice services that seek to engage positively with children who have committed crimes inevitably find themselves responding to family discord, drug and alcohol problems, school exclusions, physical, mental and emotional health issues, sexual and physical abuse, neglect, isolation, bullying and unemployment. A child or young person’s criminal offending is often the tip of an iceberg that the limited range of resources available to a youth justice team are inadequate to address. In addition, legal principles of proportionate punishment and deterrence rarely sit neatly with a child’s need for care and welfare.

The social and economic circumstances of young people are the focus of the first activity because they are the context for any and all youth justice work.

Activity 1 Lazy, idle snowflakes or hard times for the young?

Read this 2019 article by Edward Yates of the University of Sheffield which outlines the economic predicaments faced by young people.

How Britain’s economy has wronged young people for decades [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)]

The article refers to ‘three solutions’. Complete the following statements based on the article’s recommendations and analysis:

Discussion

Life has never been easy for young people with few resources. The crimes that young people commit may damage their communities and victimise people already made vulnerable by wider social conditions, but it is only by attending to the repair of those conditions that lasting change for the better can be accomplished. Working for decent pay in jobs that provide some meaning to life rather than just profit for the owner of the business is part of a struggle that stretches back much further than the banking crisis of 2007–8. Real change in the balance of power in the economy is achieved by organisations, such as trade unions.

The first principle guides youth justice practice towards seeing young people not as problems to be solved but as people whose social and economic conditions generate anti-social behaviour. It encourages a focus on these conditions and how they determine the contexts in which young people live and grow to adulthood, and how they might be changed.