3.2 Exercise and mental health

Exercise benefits everyone but most people struggle to integrate sufficient physical activity into their lives.

For young people, the World Health Organization recommends ‘at least an average of 60 minutes per day of moderate-to vigorous-intensity, mostly aerobic, physical activity, across the week’. (WHO 2020a, p. 25)’. The evidence for the physical benefits of exercise is well established, and the evidence for psychological benefits is mounting. In the next activity you will consider some of the research in this area.

Activity 7: Can 10 minutes exercise a day can improve mental health

Listen (or watch) Video 6 where Dr Rangan Chatterjee talks to Dr Brendon Stubbs. Try not to get too bogged down in detailed descriptions of research approaches here. Whilst they are important, it’s perhaps more important to consider what the key messages here are in terms of the amount of exercise and how this can impact mental health. As you listen make a note of three key messages which you feel are important.

Transcript: Video 6: How 10 Minutes Of Exercise A Day Can Change Your Brain: Dr Brendon Stubbs | Bitesize

Discussion

There are many important messages presented in this podcast and you may have been surprised that it takes as little as ten minutes a day of gentle exercise and moving to have an impact on mental health. These changes can be quite significant, as Dr Rangan Chatterjee and Dr Brendon Stubbs describe, including neuroplasticity and changes to brain activity and function. Furthermore, they discuss how these changes can take place in a relatively short period of time. This can provide important information for young people who are experiencing mental health problems who may feel lethargic and find the thought of intensive exercise daunting and hard to become motivated for.

WHO (2020b) has claimed that there is ‘Strong evidence’ that ‘physical activity reduces the risk of experiencing depression’ (p. 39) and can help to treat existing depression. WHO also warns about the health risks of excessive sedentary behaviour, which can occur, for example, when recreational activities are screen-based rather than physical.

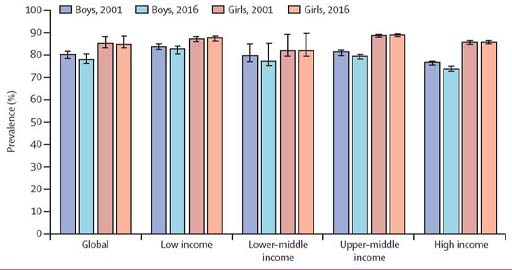

The latest figures suggest that very few young people are achieving the WHO recommended levels of physical activity (Guthold et al., 2020). The figure below, which shows the prevalence of insufficient physical activity among school-going adolescents, reveals that globally more than 80% of girls did not achieve the recommended level in 2016, and that boys were only slightly better. There is no clear pattern between rich and poor countries. The trend shows a slight improvement for boys between 2001 and 2016, and hardly any change for girls.

Research on the relationship between physical activity and mental health usually raises further questions. For example, are team sports better for mental health than exercising alone? A recent European survey study (McMahon et al., 2017, p. 120) found that ‘Lowest levels of anxiety and depression and highest level of well-being were found among those participating in team sports’. However, the researchers could not say whether the social aspects of team sport improved mental health and wellbeing, or whether the young people with mental health problems were less likely to engage in team sports.

The amount of exercise required for mental health might not be quite as great as that for maintaining physical health. Indeed, The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, n.d.) recommends ‘45 minutes to 1 hour per session, up to three times a week’ for an adolescent who has a diagnosis of depression. As more research results become available, people’s understanding of the relationship between mental health and physical activity will become more sophisticated. Increasing one’s levels of physical activity can benefit some individuals more than others, and it is definitely something worth persevering with, in efforts to boost mood.

Research note

It is difficult to make definite claims about whether physical activity actually prevents mental health problems, because most studies are ‘cross-sectional’. A cross-sectional study takes a snapshot at a particular time, by conducting a survey, for example. Surveys can determine how many people who engage in a certain amount of physical activity are experiencing mental health problems (providing a correlation), but they cannot tell whether the activity is preventing mental health problems from developing. Longitudinal studies, which measure changes over time, can help to fill these knowledge gaps, although the causes of mental health problems are so complex it can be difficult to identify the effects of a single factor. Randomised controlled trials are able to measure the effects of a single factor through careful design and the use of sophisticated statistical methods. These are the most difficult to set up, but provide the most conclusive results.

One of the ways in which exercise is thought to be beneficial is by improving sleep quality (Brand et al., 2017). Daytime exercise is beneficial, whereas vigorous exercise late in the evening can interfere with sleep. Next, you’ll explore the impact of sleep on mental health, as well as ways of helping a young person to sleep better.