2 Variable stars

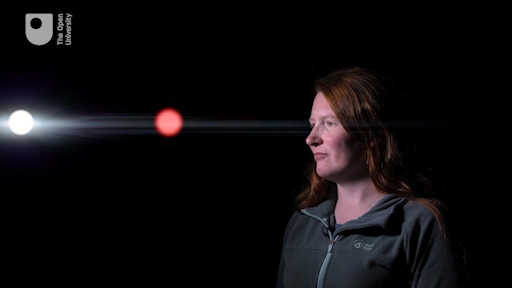

In this video, Jo explains three different causes of variability: pulsating stars, such as those passing through the instability strip; eclipsing binary stars; and finally even more dramatic exploding stars.

Transcript

In the next sections, you will look at each type of variable in turn.