3 Harkis and Pieds-Noirs: Comparing their reception in France

The European-Algerian colonists, popularly known as Pieds-Noirs (literally, ‘black feet’), who had reluctantly left for France, were designated by the government as ‘rapatriés’, repatriated French citizens or returnees, even though most had never been to France before. Such a massive migration, channelled mostly through the port city of Marseilles, overwhelmed administrators. Local residents initially reacted with animosity to these new arrivals. Nonetheless, the integration of the Pieds-Noirs (who were mostly Christian and Jewish), classified specifically as ‘European repatriates’, was prioritised by the government, which provided temporary housing in requisitioned hotels or other urban settings.

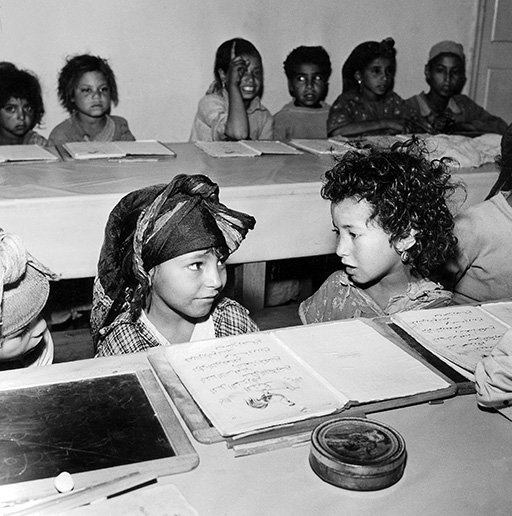

The Harkis were also categorised as ‘returning’ French nationals, but their housing needs were considered secondary by the Ministry of Repatriates and were often sub-standard, the most notorious being the rural transit camp. Almost half of Harkisrelied on kin networks to find their own accommodation in France, but more than 40,000 passed through designated transit camps from 1962 to 1964. Some remained in camps for years. The facilities that were provided were noticeably poorer than accommodation offered to Pieds-Noirs. The Harki camp at Bias, southeast of Bordeaux, for example, was a former refugee and prisoner of war camp isolated from nearby towns. Harki families were given small rooms in rows of dingy barracks within a fenced perimeter. A supervised gate controlled the entrance and exit of residents, and a 10 p.m. curfew was enforced. Cockroaches and rats were a persistent problem at Bias. With limited washing facilities, conditions were often unhygienic. Basic schooling was provided at the camp itself, so that the children of Harkis, like their parents, remained segregated from local French communities. Finding employment was difficult and Harki wives, who tended to speak less French than their husbands, were even further isolated. Similar conditions, and sometimes worse, were experienced at many of the transit camps to which Harkis were assigned.

For the Harkis, the most plausible explanation for their comparatively poor treatment was racial discrimination, compounded by growing anti-Muslim sentiment. The fact that the Harkis fought to preserve French imperial control over Algeria was ignored once they arrived in mainland France. Traumatised by war and exile, and demoralised by the condescension and paternalism of camp administrators, some of whom were Pieds-Noirs French Algerians, many Harkis withdrew into stoic silence. However, their children who grew up in the transit camps, the forestry work camps or the urban estates designated for the more ‘advanced’ Harkis, became increasingly vocal about their rights and those of their parents as French citizens.

Activity 1

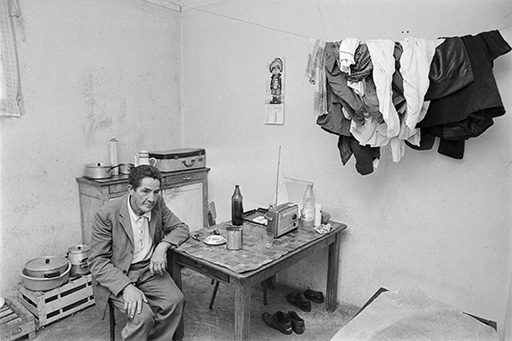

Consider the image in Figure 3 below of the middle-aged Harki man in his single room in the barracks of the reception camp at Bias. The picture was taken by a photographer for a French press agency in 1975. This was the year that protests broke out at the Bias camp, when the adult children of Harki parents demanded an end to their marginalised status.

Answer the following questions:

- Based on close observation of the photograph, what might you expect were some of the main concerns that the Harki protestors had about their lives in the camp?

- Considering the date of the image in relation to the end of the Algerian war, how would you estimate the success of the repatriation scheme for Harki integration?

- What do you think might be some concerns that should be kept in mind when using a photograph as a historical source for an issue such as racism?

Discussion

- Based on the photograph, it is likely that the protests included concerns about living conditions and poverty. The solitary Harki man in his humble room lacks space and any home comforts beyond the bare essentials of a table, chairs and sideboard. He has nowhere for his clothing besides a wire strung across the room and some of the bare walls appear spotted with mould. His stooped posture and weary expression also suggest the possibility that protesters spoke out about the mental and social isolation that Harki elders were experiencing in the camps.

- Transit camps such as Bias were opened in 1962 to temporarily house Harkis and their families until they could be integrated into French communities. The image was taken in 1975, however, indicating that some Harkis were still living in sparse and isolated accommodation more than a decade after the end of the Algerian War, long after most Pieds-Noirs had been housed and were well-integrated into communities across France. The impact of racial stereotyping on individual lives is complex and multi-faceted, but a photograph is only a single snapshot of a moment in time. We do not know if the French press photographer framed the image of his apparently pensive and isolated subject to match the aim of an accompanying article, or whether he accurately captured the Harki man’s reality. One of the residents of the camp at Bias later complained, for example, that the dominant image of the Harki at that time was that of the ‘eternal submissive auxiliary, docile and faithful’ (Eldridge, 2009, p. 104), rather than one which recognised their perseverance and fortitude in the face of trauma and discrimination.