Session 2: Human ‘zoos’ in the nineteenth century

1 Introduction

This session was written by Dr Suki Haider

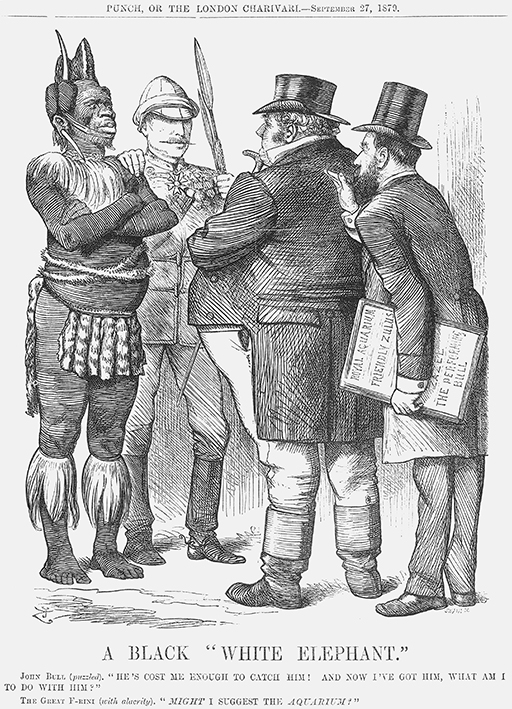

Text below illustration in Figure 1

John Bull (puzzled). “HE’S COST ME ENOUGH TO CATCH HIM! AND NOW I’VE GOT HIM, WHAT AM I TO DO WITH HIM?”

The Great F-RINI (with alacrity). “MIGHT I SUGGEST THE AQUARIUM?”

The satirical cartoon in Figure 1 shows the Zulu Chief Cetewayo (c.1826–1884) who had recently been captured by colonists. John Bull, the caricature representative of the British people, wonders what to do with him, while the man at the right of the cartoon is a showman who displayed African people in human ‘zoos’. From the weekly magazine Punch, or the London Charivari, 27 September 1879.

Living Indigenous people, from parts of the world colonised or under the influence of European colonisers, were exhibited throughout Europe and North America in the nineteenth century. Initially, the voyeuristic shows took place in private houses. By the end of the nineteenth century Africans, contracted to perform as ‘savages’ in re-enactments of recent battles, were a feature of the mass entertainment offered at the international fairs that toured Europe. The complex history of so-called human ‘zoos’ reflects the changing viewing context and evolving relationships between audiences, agents and human exhibits. As the leading historian of this phenomena Dr Sadiah Qureshi explains, some spectators were disgusted, others talked to, gave gifts to, shook hands with, danced with and had relationships with the exhibited people (Qureshi, 2011, p. 278).

Throughout the century promoters appealed to white spectators’ curiosity. They were keen to distinguish their ‘exotic’ exhibits from Britain’s resident ethnic minority populations. There was also fascination with foreign peoples as natural history specimens and the shows enabled the public to engage in the then current social Darwinist debates about human difference. In Britain, many professional anthropologists had close associations with live human exhibitions until the early twentieth century, when scholarship demanded that research of Indigenous peoples was carried out in their own environment. In this session, you will consider two contrasting examples of human exhibitions.