2.1.3 Ice tray experiment explained

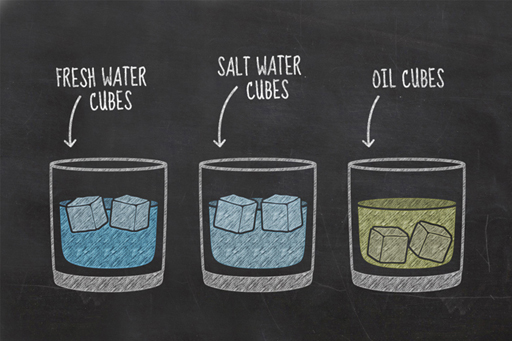

The simple experiment you performed this week has revealed some interesting properties about different liquids. You will probably have seen that the water-based cubes floated, while your other choices sank. While you might be more familiar with water ice floating on liquid water, this is actually a very unusual physical property, and our guess is that whatever liquid you froze for your fourth glass, like the oil, sank within its liquid form.

To understand these results, we first need to understand the physics behind whether objects float or sink at all. This relates to the object’s density.

Density is a concept that sometimes confuses people, but it is simply the amount (mass) of something that is contained within a certain volume of space. For example, if you have one person in an elevator, it is not densely packed, but if you try and squeeze ten people in, things are going to get a bit tight. In this case the number of people is the amount, or mass, while the elevator is the volume of space. Mass is typically measured in grams, or kilograms, while volume is typically measured in cm3 or m3, so the units for density are usually g/cm3, or kg/m3.

It is the contrast between the density of the liquid and the density of the frozen cube which is important in determining whether that cube floats or sinks.

Earlier this week, you learned about the differences between solids, liquids, and gases. When most liquids freeze the individual atoms and molecules move closer together, allowing more to fit into a given volume. As a result, these substances are more compact in their solid state than in their liquid state, in other words, their density increases.

This is why the frozen oil and frozen honey sank in Janet’s experiment. What is it about water that made it behave differently?

When water freezes, the molecules of water stick together in an unusual hexagonal structure which spaces them further apart as a solid than as a liquid. This makes ice less dense than water, and is why ice floats. Very few liquids are denser than their solids. Gallium, bismuth, antimony and germanium are four other examples, but they’re not very common. This is why we felt safe to assume that whatever liquid you froze for your fourth glass also sank.