1.2 Racism in the US Army

The French were unusual in being so willing to absorb African-American soldiers. As David Olusoga shows, while the French were willing to include the Black soldiers in their ranks, the British were not. Pershing transferred the four regiments of the 93rd Division to the French Army which removed ‘a perceived problem’. He offered the British the 92nd Division. ‘But the British, who had refused to deploy both African and Caribbean troops from their own empire to the Western Front, had absolutely no intention of absorbing into their ranks America’s unwanted black regiments and so refused Pershing’s offer’ (Olusoga, 2014, p. 343). It is worth noting that they were more than happy for white American troops to serve under their command. As for the US army, even when Black soldiers were allowed to fight, they were treated like second-class soldiers, as we will see in the next activity.

Activity 1 Racism in the US armed forces

Debra Sheffer provides an example of when men of the 92nd division were allowed to fight alongside the AEF. Read her article here Racism in the Armed Forces (USA) [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] . What went wrong for the Black troops on this occasion?

Comment

As Debra Sheffer explains, the 368th Regiment of the 92nd Division participated in the Argonne Offensive in September 1918 but without being supplied with the necessary tools and weapons. White officers then accused them of cowardice and saw their low expectations of Black soldiers confirmed. Sheffer argues that the division was haunted by this experience ‘for years after the war’. She contrasts this experience with that of the 93rd Division which served under the French.

The 369th regiment became part of the 16th Division of the French Fourth Army. They felt like ‘forgotten children’, as Major Arthur Little, a white officer in the regiment, described: ‘Our great American general simply put the black orphan in a basket and set it on the doorstep of the French, pulled the bell and went away’ (Olusoga, 2014, p. 343).

Arthur Little later stood up to defend Black servicemen who were being singled out for often brutal treatment by the American military police after the war had ended. At least on one occasion, Little intervened to prevent more serious trouble. Little was later told by a police captain that he had been instructed to deal harshly with the ‘Niggers’ of the regiment, ‘just as soon as they arrived, so as not to have any trouble later on’ (cited in Williams, 2010, p. 192).

This was not the only way in which African-American combatants were treated differently to their white countrymen. In sharp contrast to the propaganda poster in Figure 1, African-American soldiers would have looked different in the field to the ones whom the artist, Charles Gustrine, depicted as fighting for ‘liberty and freedom’ beneath Abraham Lincoln’s benign gaze. African-American soldiers were given poor quality cast-off uniforms or overalls which were considered unsuitable for the combat troops. Due to the lack of preparation for the war, some of the early African-American units were kitted out in old Union “Blues” – Civil War-era uniforms, dug out of the stores by an enterprising quartermaster. The men who wore those uniforms, the sons and grandsons of slaves, went off to war in the uniforms of the army that had won their emancipation (Olusoga, 2014, p. 339).

The 20 per cent of African-American soldiers who made it to the front and fought with the French army retained their American uniforms but wore French helmets, while their white comrades wore the British helmets that had been supplied to the US army. Upon joining the French Army, the African-American soldiers swapped their American Springfield rifles for French Lebels. Their long bayonets can be seen in Figure 1. The poster, showing well-equipped and smartly-uniformed Black soldiers fighting gallantly against portly Germans with an array of hand-held weapons while carrying forward the American flag, is far removed from reality. (It serves as another useful example for the study of wartime propaganda we undertook in Session 2). The soldiers may well have been ‘true sons of freedom’, as the poster suggests, but they were not treated like true sons of the USA during, or indeed after, the war.

Some African-American troops saw action on the Western Front, for example at the Second Battle of the Marne in July 1918 and the Meuse-Argonne offensive of 26 September to 11 November 1918 (both saw great losses for the Americans). This included the 369th Infantry Regiment, which had been trained and sent to France having been promised that they would fight there (Olusoga, 2014, p. 341). They proved to be an effective fighting unit and were feared by the Germans for their tenacity (hence the name ‘Hellfighters’). In fact, the contribution of the 369th was impressive, as Barbara Lewis Burger, an archivist at the National Archives in Washington, explains:

The 369th proved the skeptics wrong and went on to achieve a remarkable combat record: they served more time in continuous combat than any other American unit — the regiment fought for 191 days on the front, the longest of any unit; never lost a man captured; never lost a foot of ground to the Germans; and was the first Allied unit to cross the Rhine River during the Allied offensive. In recognition of its bravery under fire, the French government awarded the regiment with the country’s military decoration, the Croix de Guerre [French Iron Cross]. In addition, 171 men of the regiment were also presented with an individual Croix de Guerre for their valor. Several soldiers were also awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. The 369th was not the only black World War I regiment, nor the only one to fight valiantly, but it is perhaps the most famous.

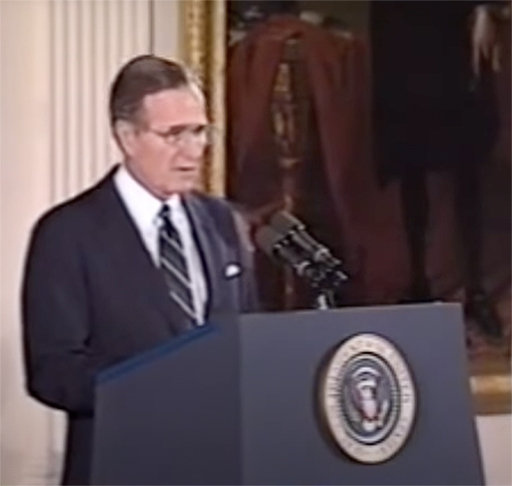

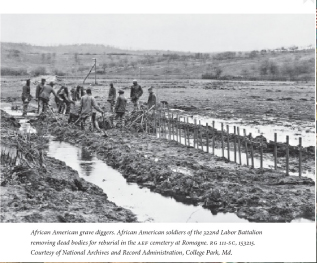

Among the 171 members of the 369th Infantry Regiment who received an Iron Cross for bravery, Private Henry Johnson was the first US soldier to receive such an honour. In the 371st Infantry Regiment, Corporal Freddie Stowers was recommended for a Medal of Honor (the highest US military award for valour) for saving his troops during an ambush despite being mortally wounded. However, this award was only given posthumously in 1991 by President George H. W. Bush. Stowers was the first black soldier honoured with a US Medal of Honor from the First World War, 73 years after he was recommended for it.

Did you know?

More details on Stowers can be found on the National Veterans Memorial and Museum.

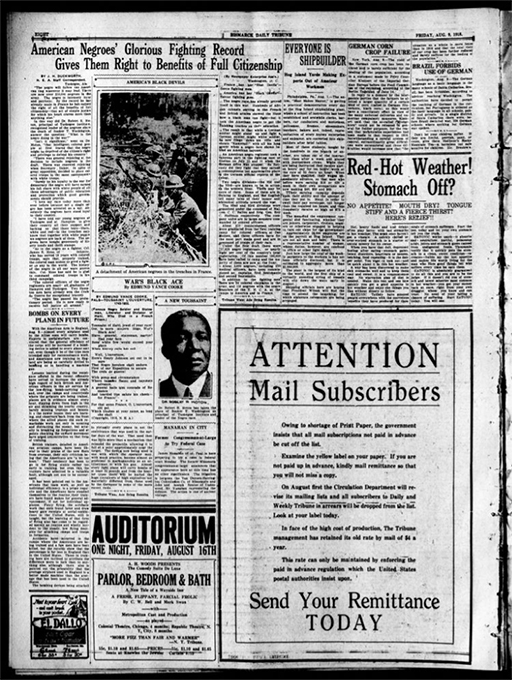

After the war, newspapers like the Bismarck Daily Tribune (Figure 3) may have suggested that African-Americans had earned the right of full citizenship, but in reality the veterans were treated no better than before the war. Segregation and discrimination continued. African-American veterans held a victory parade in New York on 12 February 1919, but were not allowed to take part in the larger parades held in New York and Washington in July. When 25,000 members of the AEF marched down Fifth Avenue in New York on 19 July, African-American soldiers were absent. Worse still, whatever hopes they may have harboured of being treated better by their fellow Americans after the war vanished in the light of at least 19 lynchings of African-American soldiers in 1919 alone, some of whom were attacked for wearing their uniform in public. Black communities were attacked in 26 American cities in what was known as the ‘Red Summer’ of 1919 (Olusoga, 2018).

Did you know?

Some photographs and newspaper coverage of the February parade can be found on the Library of Congress Blogs. You can watch some film footage of one of the July parades.

In the next section, you will explore attitudes towards colonial troops in the French Army.