2.2 War poetry – Example 2

Here’s another example of war poetry as a primary source: Wilfred Owen’s iconic poem ‘Dulce et Decorum est’.

Students’ skills development: analysing the poem ‘Dulce et Decorum est’

Wilfred Owen ‘Dulce et Decorum est’ (1918)

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.—

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

(Owen, 1920, p. 15)

Analysis

Answer

The author, Wilfred Owen, was a junior officer who served on the Western Front with the Manchester Regiment.

Answer

We know that the poem was first drafted in late 1917 and completed in early 1918. By this stage in the war, major battles, including the Somme and The Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele), had resulted in enormous death toll for the British. War weariness and, in some cases, disillusion can be detected in personal accounts from this period. In early 1918, the German Spring Offensives forced the allied forces back and led many in Britain to fear that they would lose the war.

Answer

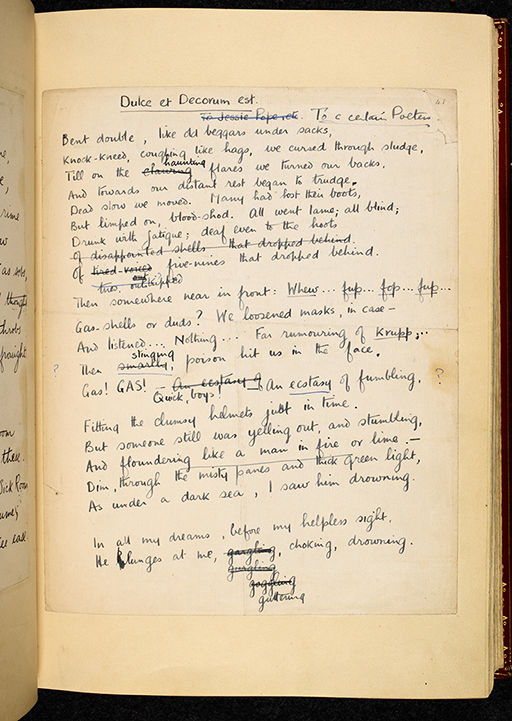

Owen first started writing the poem when he was being treated for ‘shell shock’ in Craiglockhart hospital in Scotland. Here, he had the time to reflect on what he had witnessed whilst serving in the trenches.

Answer

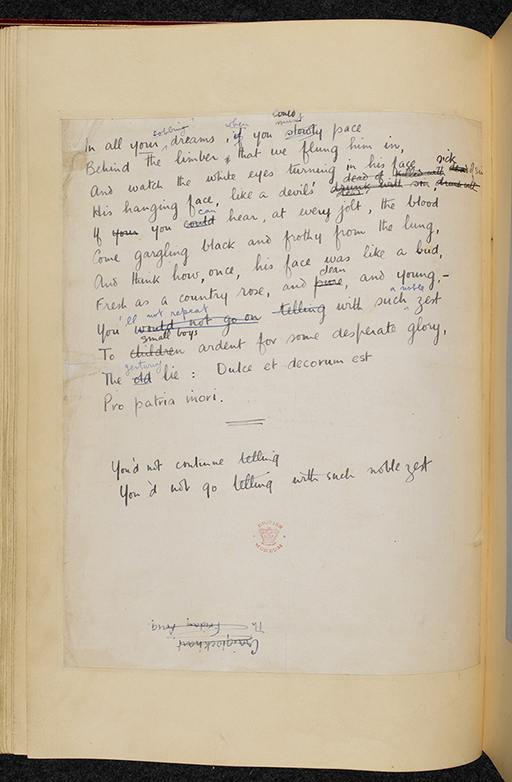

By depicting, in vivid detail, the horrific effects of a poison gas attack on a soldier, Owen challenges the notion that ‘it is sweet and honourable to die for one’s country’ (‘Dulce et Decorum Est Pro Patria Mori’). This was a well-known Latin phrase at the time (taken from the Roman poet Horace), which was used on many memorials and monuments to justify death in service of one’s country. Owen argues that if people at home could see the horrors that he had witnessed they might not be so inclined to rehearse this patriotic rhetoric (‘The old lie’).

Some published versions of the poem are addressed to ‘a certain poetess’. Owen is referring here to Jessie Pope (and in fact addressed a draft of the poem directly to her), so ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ should be seen as a riposte to poems like the ‘The Call’ (discussed above).

Answer

It’s important to note that, although the poem was written during the war, it was not published until 1920 (Owen had been killed in action in November 1918). Owen is now the most famous poet of the war, but he was not well known during the conflict and only a few of his poems were published during his lifetime.

Unlike popular wartime poets like Rupert Brooke, Owen’s poetry was not printed in newspapers and did not appear in bestselling poetry collections during the conflict. For this reason, we should not assume that his views reflected or influenced the views of the wider population during the war – it was not until later in the twentieth century that Owen became a recognised and celebrated poet.

Answer

The poem is useful for its descriptions of the impact of a poison gas attack, a subject which is dealt with in very few other poems from the First World War. As Owen experienced similar events himself, the poem can read as a form of first-hand testimony from the front. Owen depicts the chaos and confusion of the gas attack (‘An ecstasy of fumbling/Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time’) and the potentially devastating effects of poison gas on the human body (‘the froth corrupted lungs’). The poem also provides a prime example of protest against the conditions of the war and especially against the patriotic rhetoric that abounded on the home front.

Answer

Despite these uses, we also need to be aware of the poem’s limitations. First, as noted above, we should not assume Owen’s poetry reflected broader views regarding the war whilst it was taking place. It’s also worth noting that Owen was a well-educated officer: his views did not necessarily reflect those of other soldiers. Many soldiers maintained a patriotic outlook and not all protested against the war. We also need to bear in mind that this poem is an imaginative response to the war – we cannot say for certain that it is an entirely accurate depiction of scenes that Owen himself had witnessed.

For the purposes of this activity, you will probably find it most useful to work with the reproduction of the poem above. But students might also be interested in seeing the manuscript version in Figure 3. Students could be asked to reflect on the various changes that Owen has made to this draft of the poem. It was first addressed directly to ‘Jessie Pope’, for example, before Owen changed this to ‘a certain Poetess’.

Did you know?

The following online resources are useful for finding other poems and useful contextual information:

First World War Poetry Digital Archive [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)]

In the next section, you’ll explore how war art can be interrogated as a primary source by historians.