8 Finding and assessing online primary sources

Finding appropriate primary sources both for classroom use and for students to employ in their work is somewhat easier than locating good secondary sources. That is not to say, though, that there aren’t snags, or resources that you might have overlooked. Before giving an overview of some of the most helpful primary source collections for studying the First World War, let’s look briefly at some principles and safeguards for when you search. No doubt you’re familiar with these, but it is probable that your students aren’t.

To begin with, some websites present very partial information, in both senses of the word. Others are pressed into the service of a preconceived ideological agenda. This is perhaps less problematic in the case of our chronological period than it would be, say, for the Soviet Union or Nazi Germany, but deceptive sites do exist, nonetheless. More troublesome can be those sites, such as Pinterest, that are not obviously curated and instead rely on the good will and sense of those who contribute to them; the chances of an inaccurate or misleading source appearing on those sites by accident are much higher than on established ones on which there is some editorial oversight.

Of course, you will come across many web pages that offer collections of primary sources. In this case, you need to ask whether they are presented in full or edited in some way (the latter need not make the internet site unreliable, but it should make you wary). Some primary sources are a little more difficult to alter – visual sources are the principal example – but still there are cases of visual material being altered or faked (sometimes for the purposes of humour) and subsequently being taken as genuine historical artefacts.

When students are required independently to find their own primary sources, as they generally have to for A-Level NEA projects, they are likely to be less discriminating. It would be helpful, then, to offer them some basics in assessing primary source collections, and – as with secondary sources – steer them away from generalised Google-type searches.

The resources we list below are all robust and sufficiently scholarly, but they are far from the only collections available. On discovering a primary source anthology, students first need to enquire of its provenance and presentation as a collection. That critical assessment is, in fact, a hybrid of the document analysis techniques that we employ throughout this course and the types of questions that we looked at above when evaluating secondary literature.

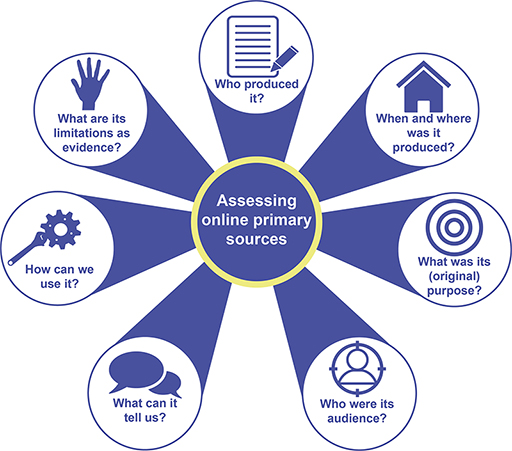

Each of the other sessions of this course uses a series of questions to interrogate the provenance, nature and potential uses of primary sources. Essentially, they are:

No doubt you use a comparable typology in your classroom practice, and you’ll have noticed, too, that some of those questions resemble those asked in the PROMPT model. Encouraging your students to ask similar critical questions of online primary source collections is likely to help them assess their value for assignments and other assessment tasks. The most crucial ones to pose here are: who put this together, why and on what principles?

For most collections, this is relatively easy – almost invariably the more trustworthy sites will explain their purposes, sources of information, curation guidelines and limitations in a separate information page, frequently labelled ‘About’ or ‘Info’. For a particularly good example, look at the collaborative National Archives/IWM ‘First World War: Sources for History’ website. If an online collection does not provide that type of explanatory material, it may be better for students to avoid it.

The second consideration to be aware of is the structure of the database. This is complicated by the fact that primary source collections are frequently structured in a more inconsistent way than secondary source databases. There are plenty of good quality websites containing valuable primary material that, often because of their age, are structured as thematic or chronological lists. Although a lot of these have taken to providing a rudimentary search function with a customised Google search, nonetheless they can be laborious to go through without a clear idea in advance of what one is looking for.

Two otherwise excellent collections that suffer from this snag are the Avalon Project and First World War.com. That said, an increasing number of sites offer the facility to employ more sophisticated forms of search on their holdings, as we saw in the case of JSTOR. Of these, one of the best is the First World War Poetry Archive, which has a well-structured advanced search page and the facility to browse sources by tags (such as ‘propaganda’ and ‘medicine’). Another well-arranged website of that type is Oxford University’s World War I Centenary collection. You encountered these websites in the course sessions on ‘Memory and Representation’ (Session 4) and ‘Propaganda’ (Session 2) respectively.

Activity 5 Evaluating an online primary source collection

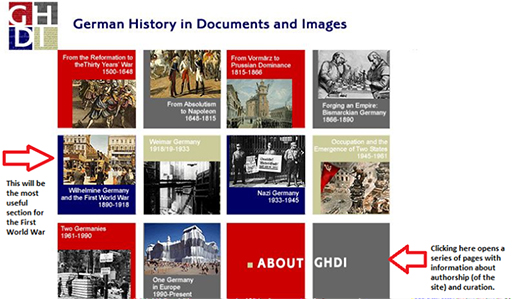

An excellent site for primary sources on the First World War is German History in Documents and Images. Take a look at the site and evaluate its usefulness for your students. This activity would also make relatively quick classroom activity to give your students confidence in critical assessment of online collections allowing them to explore it by concentrating not on individual primary documents but rather on its authorship, purpose, principles of construction and structure.

Comment

The site has an unusually detailed information section, which has several subpages outlining much of the information for which the students should be looking. For instance, the page on ‘editors’ gives a list of the scholars who have been involved in the direct authoring on the site, and their academic affiliations, while the ‘overview’ page explains the purpose of the site, its processes of compilation and how it is constructed.

Moving to the individual section on ‘Wilhelmine Germany’ will demonstrate the site’s arrangement in practice. Under ‘Introduction’, there is a series of secondary commentaries written by specialist academics, detailed biographies of whom are available under the ‘Editor’ tab of each article.

The other tabs reveal lists of sources, each of which has an explanatory headnote written by the academic editors. We suggest looking for ‘mobilization’ within the period ‘1914–18’ to demonstrate the search capacities of the site; it should bring up at least 14 sources of different types, and will, incidentally, allow you to make a point about different common spellings to your students (‘mobilisation’ does not return any hits!).

In the next section you’ll be introduced to some other useful online resources.