3 Using Google Scholar

Since it is likely to be your first port of call for a lot of secondary texts, this first activity uses Google Scholar.

Activity 1 Finding literature using Google Scholar

Imagine that you are searching for suitable secondary literature on medicine in the First World War, specifically on the effects of shell shock. This is a reasonably common topic at both GCSE and A Level, and some exam boards may allow students to write their NEA projects on the subject. Spend a few minutes considering what search terms you might employ to return the best results in Google Scholar, and then use them to conduct your own search.

Comment

I went to Google Scholar and used the following search string, which is composed of some of the elements of Boolean searching mentioned above, in the search box.

(psychology OR psychiatry) AND “first world war” AND “shellshock”.

Another way of conducting this search is through the ‘Advanced Search’ options. The search string will determine not only the documents that the site finds, but also the order in which they appear.

By default, they will be sorted by what the search engine sees as ‘relevance’ – that is, the total number of matches for the phrases in each document.

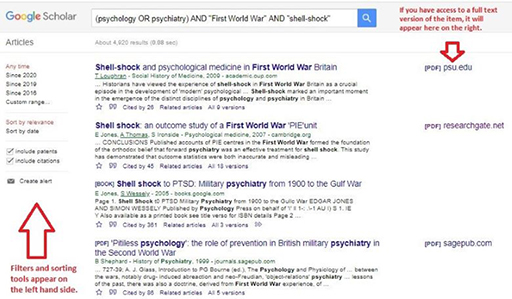

You should get a search result like the example in Figure 2. Don’t worry if it’s not exactly the same because Google occasionally tweaks its search algorithm to make sure that certain results do not always dominate the lists.

Google Scholar search results look more uniform than those produced by its standard search engine. That is because each result uses similar scholarly publishing conventions. The different elements provide further clues to help you judge the value of material you find. Underneath the title in blue, the authors are always listed in green. The host site could be a journal, as three of these are, but it could be a conference paper, a book chapter or a research paper of some kind.

‘Cited by’ gives a rough indication of the value of an academic paper by the number of times other authors have referenced this article in their own work (although, naturally, recent articles are likely to have been cited less).

‘Related articles’ provides links to other results that are similar to the article in question; this can be useful when your search hasn’t generated many results, or where you have used complex search criteria.

Lastly, ‘All X versions’ will list all the available versions found, which might include open access versions as well as articles hosted by academic publishers.

Try not to be fazed by the number of results a search generates – in most cases, there will be lots and you will need to cut them down before evaluating their quality, but that can normally be done quite quickly. You’ll see that the example of my search above found almost 5,000 items, which of course is pretty unmanageable. So, although in this case at least two of these four top items look very promising, the likelihood is that you will want to filter your list, if only to bring it down to a manageable size.