3.4.2 Disobedience for social transformation

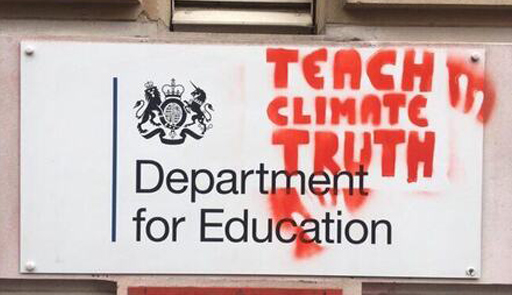

There is a huge variety of activist groups working to address the climate crisis. Some have opted for a more disruptive approach to make a stand, including being prepared to break the law. For example, the climate activist group Extinction Rebellion (known as XR) initiated a wave of acts of civil disobedience in the UK, that later spread internationally. In the US, some members of the youth-led Sunrise Movement were arrested while acting to pressure members of Congress to support green legislation.

Wright’s (2010) theory of social transformation suggests that radical societal shifts usually require a shock to the system’s status quo. Climate activists are up against powerful actors. Fossil fuel, transportation and energy companies are highly influential, politically and economically. Although young activist groups get some media attention, they are still a tiny minority of the global population and lack traditional sources of power. While Wright did not support militant resistance, he did see the importance of challenging and confronting power. In addition, Wright pointed to the reformers’ need to face and expose some ‘gaps and contradictions’. One such contradiction is the ‘capital–climate contradiction’, which refers to the contradiction between capital’s need to expand production and the destructive effects of these expansions on the climate system (Stuart, Gunderson and Petersen, 2020).

Wright’s theory of social transformation might explain young activists’ choice of action as a means of exposing and confronting ‘contradictions’. Their activism can be made even more effective if they are supported (and not stopped) by the educational systems in which they study, and by the educators who work with them. This may not be straightforward, however.

First, it’s important to move away from the notion that young people are particularly likely to engage in disruptive action, including breaking the law. For example, activists within groups such as XR include many retired people who are prepared to engage in disruptive action and to break the law as they have less to lose by doing so, and getting arrested will not affect their job prospects or career. Whatever the sector, if you’re teaching topics related to addressing the climate crisis through civil disobedience and disruptive activism, it’s important to reflect on your own views and experiences and how they might inform your teaching, be clear about your institution’s position on educators supporting students in disruptive activism, and prepare a strategy that navigates these considerations. For example, rather than supporting students in how to handle getting arrested you could direct them to the many relevant resources available, including those from XR [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] . It’s also worth pointing out that movements such as XR typically have a range of roles available that don’t involve direct action, including preparation of resources such as posters and props, administration, co-ordination and fundraising.

You’ll now further consider the teacher’s role in relation to climate activism.

Activity 6 The role of teachers in activism

Read the vignette below from Dunlop et al. (2021) that discusses the role of schools and teachers in nurturing and responding to climate crisis activism.

All teachers of 12 to 13-year-old students were asked to lead a session on the climate crisis. As part of a school professional development programme, teachers were asked by the pastoral lead to reflect on their experiences of teaching the session. A group of three teachers had been asked by students about their views on the climate strikes.

- Teacher A explained that while personally supporting the climate strikes, they did not want to voice support during the session because of concerns about students missing too much school, and the impact this would have on attendance and attainment.

- Teacher B had voiced support for the strike and for striking young people during the session followed by an explanation of how strikes work, noting that strikes need to be disruptive to work. Teacher B noted to the class that there was minimal disruption to people other than the striking young people – so if they really cared, they should schedule strike action for a weekend.

- Teacher C responded that Teacher B was wrong to voice support, because the teachers’ standards require teachers to uphold school policies and ethos and ensure teachers’ views are not expressed in ways that could lead young people to break the law.

Reflect and make some notes on the following questions:

- How might you have responded during the session with 12 to 13-year-olds?

- Would you respond in the same way to your own students, or students with whom you are familiar? If not, why not? What are the likely consequences of your response?

- In general, do you think educators should share their political views in the classroom and/or promote causes they feel passionate about? Do you feel differently about whether educators should promote their views regarding the climate emergency?

- Should educators use teaching as a form of activism? If so, are there any caveats to this? If not, why not?