1 What do we mean by systems?

The most generalised definition of systems is usually along the lines of ‘an assembly of interacting components that does something for somebody’. In common usage (and in systems engineering!) there is an assumption that systems are things that exist out there in the world, and that some of them do not work very well and can be engineered to do better. This is not a perspective supported in this course nor, more generally, in STiP.

STiP practitioners see systems as conceptual constructs or tools to help us understand and act in messy situations of concern. Unlike ‘problems’, which can be defined and solved, messy situations appear to be intractable and appear to affect everything around them. Although messy situations are seldom ‘solvable’, systemic perspectives can be applied to make sense of them and improve them. In this context, the word ‘system’ does not refer to something that exist in the world but is applied to our processes for making sense of complexity and interconnectedness. This course will introduce you to ways of thinking and acting in a complex world by designing learning systems to help you understand and change messy situations of concern framed as systems of interest. A system of interest is defined by four characteristics:

- There is an assembly of components connected together in an organised way.

- The components are affected by being in the system and the behaviour of the system is changed if they leave it.

- This organised assembly of components does ‘something’. In some cases the ‘something’ will be easily defined: the purpose of a car braking system is to enable us to stop the car.

- This assembly as a whole has been identified by someone who is interested in it.

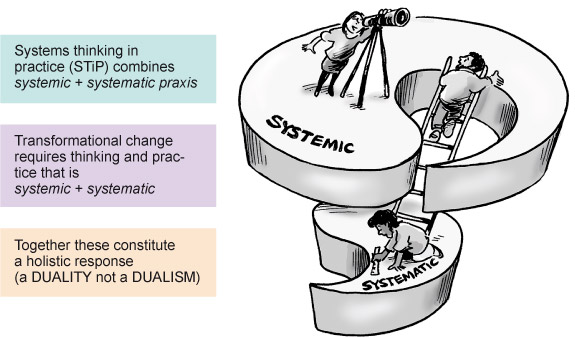

One important aspect of the definition above is that it calls for attention to the whole and to its parts, as systems thinking in practice is constituted from systematic and systemic forms of practice.

Activity 1 Understanding systematic and systemic distinctions and how these relate to STiP

Make some brief notes, and drawings if you wish, on what the words ‘systematic’ and ‘systemic’ mean to you at this stage. Do this as a brief brainstorming exercise, noting down any word associations or images that come to mind in relation to each term. How do these two terms relate to STiP?

Discussion

Systematic thinking refers to orderly thinking and practice that proceeds in a considered, linear, step-by-step, manner. It involves methodical, regular and orderly thinking about the relationships between the parts of a whole, or the stages of a process. Doing something systematically involves breaking the task down into sequential, or linear steps.

Systemic thinking, in contrast, calls for putting parts into a context to establish the nature of their relationships pertaining to the entire system, allowing for variable and possibly hidden interconnections and undetermined behaviours. If you are wondering how the different elements of a situation relate to each other, it is possible to describe your concerns as systemic in nature. They are systemic when you are concerned with relationships between elements in a system, including boundary judgments, circular causality, positive and negative feedback, and interdependencies.

Western intellectual traditions have laid greater emphasis on systematic thinking and action than on systemic thinking and action. If you are educated in the western tradition, it is often hard to escape the trap of thinking that can be described as mechanistic, linear, reductionist and systematic, with all those attributes in service of certainty and control. It is necessary to practice so as to break out of this trap, but in doing so we must be wary not to steer away from one pitfall just to walk into another. The perspective of this course is that one can also fall into a trap by considering systemic and systematic as an either/or choice. Instead, understanding systemic and systematic thinking as a duality, two mutually supportive concepts that make up a conceptual whole that when understood can be used to increase the practical repertoire available through STiP.

How you first start thinking about a situation in your practice is often very important. Distinguishing a system in a situation as a way of thinking about and acting to change a situation for the better is one of the key practices associated with STiP, and completing a systems map is a first step in engaging systemically (compared with systematically) with a situation of interest. Activity 2 will introduce you to these key practices.

Activity 2 The process of distinguishing and mapping a system

Part 1

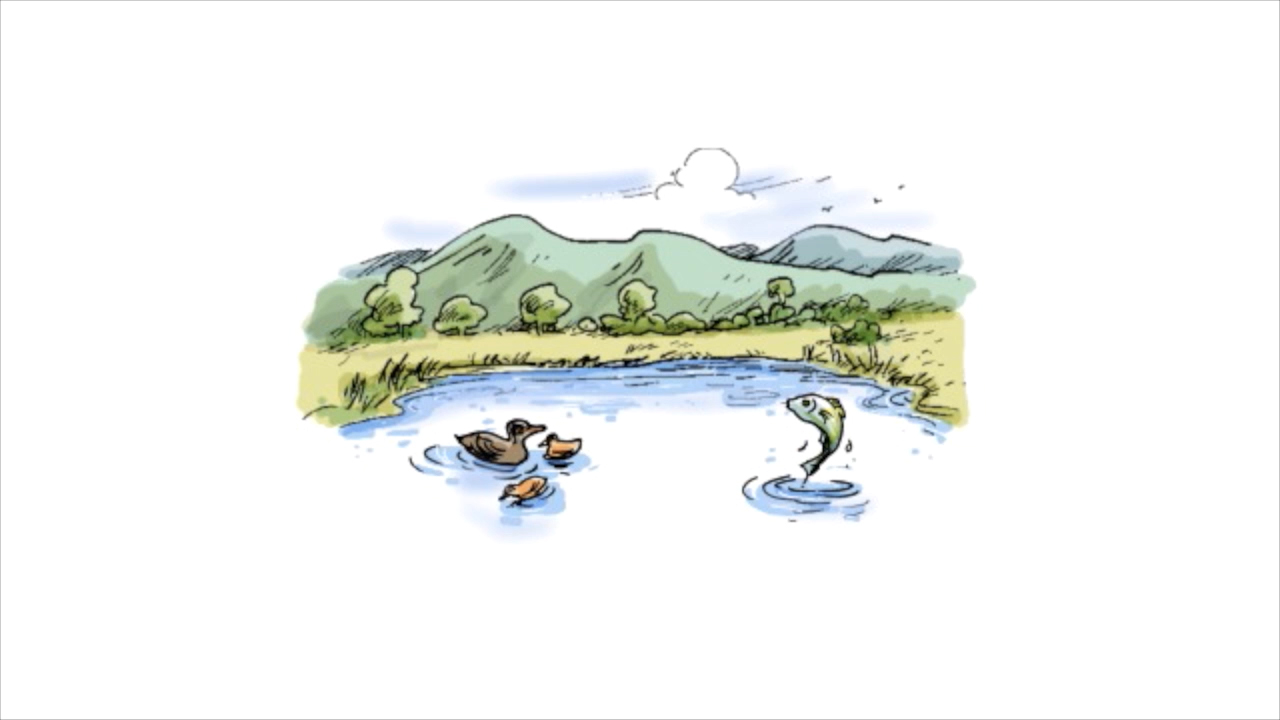

View the animation below. Consider how this relates to the characteristics of a system of interest introduced earlier. You may remember that one defining characteristic of a system of interest is that the system has to do ‘something’. The animation illustrates how the meaning of that ‘something’ can change when the system is changed.

Transcript: Video 1

The animation is of a situation in which a practitioner distinguishes or brings forth a system for the purpose of understanding or changing parts of the situation. This is one of the key practices, perhaps the key practice associated with STiP in this module.

The practitioner is also part of the situation, as depicted by their inclusion inside the bounded situation. Within the broader, amorphous situation, this practitioner distinguishes a situation of concern related to her own purpose in the situation. The practitioner, aware of her purpose, chooses to use STiP to create a system of interest within the situation of concern. This is created by making or drawing a boundary which distinguishes a system from its environment. In her practice, the system of interest arises as a relationship between a system and an environment mediated by a boundary choice or judgement made by the practitioner.

The practitioner is also part of the situation, as depicted by their inclusion inside the bounded situation. Within the broader, amorphous situation, this practitioner distinguishes a situation of concern related to her own purpose in the situation. The practitioner, aware of her purpose, chooses to use STiP to create a system of interest within the situation of concern. This is created by making or drawing a boundary which distinguishes a system from its environment. In her practice, the system of interest arises as a relationship between a system and an environment mediated by a boundary choice or judgement made by the practitioner.

The practitioner in the animation is conceiving of the situation in a particular way known only to her. She could be thinking about fish for dinner, and hence her conception of what the system does, its purpose, could be to produce fish. By seeing a system to produce fish, she is focusing first on what the pond is for from her perspective. This is what is meant by the phrase ‘creating a system of interest.’ Equally, she may be thinking in terms of protecting endangered species or of creating a garden pond.

Systems of interest are devices related to purpose so that the boundary and subsystems will be different in each particular system of interest. Systems of interests even in the same situation are also likely to differ somewhat, because each is constructed or formulated by one or more people who have different experiences and backgrounds and possibly purposes. For an aware systems practitioner, a system of interest is an epistemological device, a way of knowing about, understanding, and possibly changing elements and their relations in a situation of concern.

Comment

The woman in the animation is considering the situation in a particular way known only to her. She could be thinking about her conception of what the system does (its purpose) and focusing first on what the pond is for from her perspective. She is creating a system of interest. Systems of interest are devices related to purpose, so that the boundary and subsystems will be different in each particular system of interest. Systems of interest, even in the same situation, are also likely to differ somewhat because each is constructed or formulated by one or more people who have different experiences and backgrounds, and possibly purposes.

Part 2

Think about a system of interest, one where you would like to change things for the better. This could be related to a global issue such as climate change, it could be something happening in your community or may be a system or situation related to your professional background.

Once you have chosen a system or situation, review the systems mapping techniques in Guide to diagrams [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] , and complete a system map for your situation of interest. You may find it useful to keep this situation in mind and to refer to the map as you complete other activities in this course.

Key elements of STiP as a process include a system of interest comprising a system (with subsystems), boundary and environment which is ‘brought forth’, or distinguished, by someone as they engage with a particular situation. The process of formulating a system of interest is the same as that depicted in the animation in Activity 2. A good systems map can tell a lot about how the person or group developing the map understands. The point is that a systems map is way of knowing about a situation – it is a sense-making device or technique. System maps such as the one you completed in Activity 2 constitute one of the many tools and frameworks used in systems thinking in practice to better understand complex systems or situations. Although understanding the world is an important step, it is not an end in itself as, paraphrasing Marx, the task is not just to understand the system, but to change it.