1.3 Desert reptiles

Reptiles with a scaly keratinised skin are not so prone to evaporative water loss as amphibians and are the vertebrates that you are most likely to see on a visit to a desert. Reptiles are ectotherms and rely on solar radiation for warming the body and maintaining high body temperature (Tb) during the day. Desert reptiles have no problem in gaining heat for maintaining Tb at a high level on hot sunny days (Figure 7).

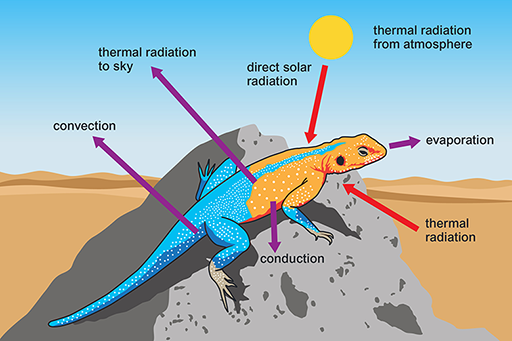

What are the sources of energy gain and routes of heat loss for the lizard?

The lizard gains heat energy via thermal radiation from the Sun, the atmosphere and the ground. Heat energy is lost via conduction from the body to the ground, by evaporative water loss, convection and thermal radiation to the sky. On a hot sunny day, more heat is gained than lost, and it is important for a desert reptile to avoid overheating. It is equally important to reduce loss of body heat when Ta plummets at night or during the winter.

During the day, reptiles may move between warm and cool areas in order to maintain Tb. This movement between warm and cool areas for maintaining body temperature is called shuttling. Those species that maintain high stable Tb when environmental conditions allow by adopting heliothermic (sunbasking) strategies, are called thermal specialists. In contrast, there are some species, known as thermal generalists, which allow their Tb to fluctuate and decline, even when they could shuttle between sun and shade to maintain high stable Tb during the day, or use their burrow at night to prevent cooling of Tb to the outside Ta. Bedriagai’s skink (Chalcides bedriagai) is a thermal generalist, preferring to spend a lot of time hiding under rocks rather than basking in the Sun.

The side-blotched lizard (Uta stansburiana), found in the Sonoran desert, is a typical thermal specialist. It is a small species, only 4–6 cm long when full grown.

In the morning, Uta warms by basking, initially orientating itself at right angles to the Sun’s rays and flattening the body against the substratum for maximum exposure to solar radiation. When warmed Uta turns the body so that it faces the Sun while resting. Uta maintains Tb around 36–38°C. Active foraging for insects, scorpions and spiders may overheat the body, and for cooling off, especially around noon, Uta moves to the shade of rocks and scrubby bushes. Shuttling in this way enables this species to stay active during the day for most of the year except in areas where winter temperatures dip to freezing.

A few desert reptiles are nocturnal; the Moorish gecko (Tarentola mauretanica), is found in arid regions in North Africa (also in Spain, France and Greece, so it is not restricted to deserts).

Tarentola is most active for a few hours after sunset. During the night, it’s Tb is as low as 18°C, and can fluctuate by up to 11°C. Those lizards that tolerate wide fluctuations in Tb, even when they could use features of the environment to maintain a steady Tb, are known as thermal generalists. The Moorish gecko is a thermal generalist at night, when it is active rather than resting in its burrow. During the early morning the Moorish gecko basks in the sunlight.

The advantage to the gecko of warming up in the morning is uncertain, but it is possible that a physiological process such as digestion of the food eaten during the night requires a higher Tb than the gecko can maintain at night.

Sheltering in the available shade in the desert, or being active at night, are simple strategies for keeping Tb below lethal levels. In sandy desert areas, the sand itself plays an important role in behavioural thermoregulatory strategies. The Mojave fringe-toed lizard (Uma scoparia) is restricted to fine, wind-blown sand, e.g. in dunes, dry lake beds and desert scrub in the Mojave desert. Burrows in sand collapse immediately or soon after the animal has moved on, so animals buried in sand rely on air trapped between sand particles for breathing. Uma is a ‘sand-swimmer’ and its dorsoventrally flattened body and shovel-shaped head facilitate movement through the sand, which is especially important when escaping from predators such as snakes.

The eyelids are protected from sand by large eyelid fringe scales. The digits have large lamellar fringes, elongated scales, especially long on the hind feet, which enable the lizards to run at speed on the sand surface. Uma grows up to about 110 mm in length, and its activity pattern is diurnal, varying according to ambient temperature. In March and April Uma is active for short periods because of the low spring temperatures in the Mojave. In summer, from May to September, the lizards are active during mornings and late afternoons, feeding on insects and plants. Sand-swimming lizards are also found in the Namib desert and include the wedge-snouted sand lizard (Meroles cuneirostris).