8.1.4 Apply Stages 1 and 2 of the financial planning model to insurance

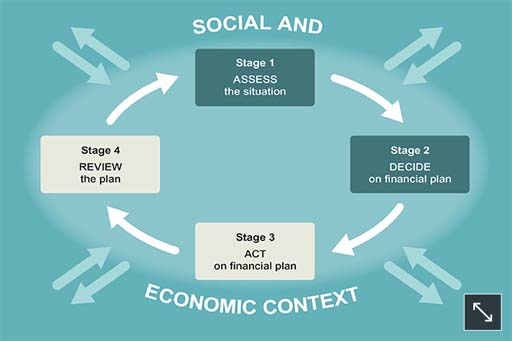

Look again at the familiar model and apply it to insurance. But remember that in practice financial planning needs to be a flexible process, with movement back and forth between the stages.

For Stage 1, where you assess the situation, it’s worth stressing the significance of the perils that can be insured against, as related insurance policies vary according to individual circumstances. Life insurance, for example, is likely to be especially important in a family with children and with one income earner, but may be regarded as irrelevant to a single person with no dependants.

An important factor to consider is what other protection is available. State benefits are part of this equation, as are any benefits available from an employer. With large employers, benefits may include sick pay above the statutory minimum, ‘death in service’ benefits and private medical insurance (PMI).

As part of your Stage 1 planning you need to find out what you are entitled to. Your entitlements may not completely replace the need for additional private insurance, but it’s important to know what they are.

The combination of what the state and an employer provide could eliminate the need for some types of private insurance, or reduce the amount of additional cover needed. The private insurance element can be seen as building on the insurance cover provided by the state and by employers.

A further factor to assess at Stage 1 is your attitude towards risk. Your aversion (or otherwise) to risk will be affected by a number of factors, including age, tastes and preferences. The more risk averse you are, the more likely you are to consider additional insurances.

Stage 2 is when you decide which additional insurance policies are appropriate for yourself or your household. As a rule, the greater the potential financial impact of a peril, the more likely it is that you will consider insuring against it. The key determinant is whether you could bear the cost of a risk materialising – even if the risk is very low.

The obvious example of this is insuring your home – rebuilding costs would be far beyond most people’s means, and so most owners decide that risk shifting makes sense (or have to do so as a condition of their mortgage).

But where the costs of the loss would be smaller, self-insurance may be considered a better alternative. To illustrate, paying the cost of domestic appliance repairs may make more sense than taking out an extended warranty.

Another factor in deciding on insurance is the cost of the insurance policy. Normally, the higher the premium, the less likely someone is to take out an insurance policy. It would be theoretically possible to calculate the expected benefit from an insurance policy, taking into account the financial impact of a peril and the probability of it occurring. However, such calculations are extremely hard to perform in practice.

Your decisions about whether to take out insurances will have a direct impact on your household budget as the more policies you take out the more your expenditure increases. Conversely, by actively seeking ways to reduce the premiums you pay, for example by fitting window locks or a burglar alarm, your expenditure will decrease. This feeds directly back into the budgeting process discussed in Week 3.

One way to think about the impact of insurance payments on your household budget is to realise that the current expense aims to protect you and your household from greater expense in the future.