2.4.6 Transaction costs

Buying investments involves transaction costs. These can include:

- the bid-ask spread

- brokerage commission/dealing costs

- transaction costs

- management charges.

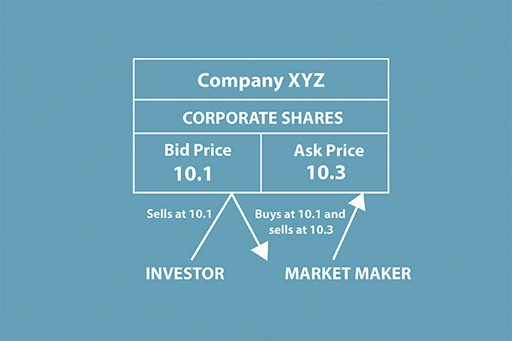

If we look first at a simple transaction of 100 Royal Dutch Shell shares, the bid–ask spread is the difference between the price at which the investor can buy the Shell shares (the ask) and the price at which the investor can sell them (the bid). Suppose that the bid–ask spread for 100 Royal Dutch Shell shares is £17.10 – £17.20. This means that the investor can sell 100 shares at £17.10 or buy 100 shares at £17.20, to allow a profit for the so-called marketmaker. The bid is the price at which the marketmaker bids for shares; the ask is the price at which the marketmaker asks investors to buy shares.

For the investor, the bid–ask spread represents a transaction cost. The price at which they can buy shares is always more than the price at which they can sell them, so there is an inbuilt capital loss from day one – in this case 10p per share. Also, the smaller the number of shares traded, the larger the bid–ask spread, to reflect relatively fixed handling costs. Institutional investors, trading in large amounts, say 100,000 shares, will experience a much narrower bid–ask spread than will the small investor.

Stamp Duty Reserve Tax (SDRT) of 0.5% is paid when shares are bought electronically (which the vast majority are these days). SDRT is not paid when shares are sold. Share prices can be seen in most newspapers that report daily on share prices as well as on other information.

It is normal to buy or sell shares through a stockbroker or brokerage firm, either by telephone or on the internet. Again, charges vary according to the size of the trade, with a minimum brokerage commission of, say, £12 for each transaction. This is a relatively small percentage of a £10,000 trade, but makes trading in £100 amounts uneconomic. Online brokers tend to be cheaper than traditional brokers as they provide no investment advice, usually restricting themselves to basic information on the companies in which they trade.

Finally, there are the management charges payable to institutional fund managers in return for choosing the investments on behalf of clients. These charges have to be disclosed in the documentation but are taken by the manager from the funds invested with them and so are rather hidden from view, particularly with long-term investments. Although a representative 1.5% annual management charge does not sound that large, it can mount up and reduce returns substantially over the long term, as, for example, with pensions. You should also check if there are any other costs like custody and administration charges. These all need to be set out in the documentation provided by the institution you are doing your investment business with.

The 2006 White Paper on Personal Accounts, published by the Department for Work and Pensions, examined the case of a male median earner (£23,000 a year in 2006/07 terms) who was aged 25 in 2012. By contributing 8% of his earnings each year for 43 years to a pension scheme, with a real rate of return of 3.5%, he would have a pension fund worth £87,000 at the age of 68. With a 1.5% management charge, typical of active pension fund management charges, the fund would be worth only £63,000, with £24,000 having been deducted in management charges. With charges of 0.5 per cent instead of 1.5 per cent a year, the fund would be worth approximately 25 per cent more on retirement.