2.1.1 The experience of invasion and occupation

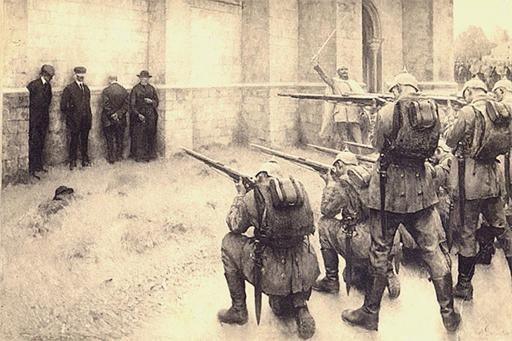

During the First World War, some traumatic acts of reprisal occurred against civilians in neutral and occupied countries on a scale which was shocking to contemporaries.

The atrocities committed by German soldiers in Belgium and France in 1914 provide some of the most prominent examples of the war’s impact upon civilian populations, though atrocities were also committed by other armies and in other contexts. In the Belgian and French examples, such acts were partly motivated by the memory of previous wars. The so-called franc-tireurs of the Franco-Prussian war of 1870–71 had instilled a deep-rooted fear of partisans in German soldiers. A stray bullet, the news of an alleged poisoned well, or other acts of real or imagined resistance could be seen as evidence of such action and lead to the punishment of scores of suspected partisans and innocent civilians. Cultural differences, including antipathy towards the local Catholic population, also inspired the violence. What is clear, however, is that these atrocities were not part of a premeditated military strategy; rather, they developed as part of the frightening reality in which soldiers and civilians found themselves.

In 1915, the Austrian psychologist Sigmund Freud commented that the violence against civilians

disregards all the restrictions known as International Law which in peacetime the states had bound themselves to observe; ignores the prerogatives of the wounded and the medical service [and] the distinction between the civil and military sections of the population … The civilized nations know and understand one another so little that one can turn against the other with hate and loathing. Indeed, one of the great civilized nations is so universally unpopular that the attempt can actually be made to exclude it from the civilized community as ‘barbaric’.

Such acts of barbarism were attributed to the German army by its enemies. Following the German invasion of Belgium in August 1914, the German army swept through towns and villages, with little regard for the local inhabitants. Having already killed 640 civilians in the area around Liège, the German army invaded the city of Louvain on 19 August. Over a period of five days, beginning on 23 August, the invaders attacked civilians and burnt down buildings. The university library, for example, which housed numerous ancient manuscripts, was burnt to the ground – this act of wanton violence would become a powerful symbol for the barbarism of the German army in Belgium. Pillaging was rife, and it is estimated that around 248 civilians were deliberately murdered in Louvain. Similar atrocities were committed elsewhere in Belgium and northern France.