2.2.3 The global consequences of the war: the ‘Spanish Flu’

Food shortages, of course, were not peculiar to Germany. The reallocation of resources and manpower towards the war effort restricted the supply of food in all countries.

In Russia, on the eve of revolution, bread was the first demand voiced by demonstrating women. In Britain, rationing was introduced in 1918, though crucially never for bread (something that the Russian authorities might have been well advised to copy). Malnutrition, and an increased susceptibility to diseases such as scurvy and tuberculosis, became a serious problem as the war went on.

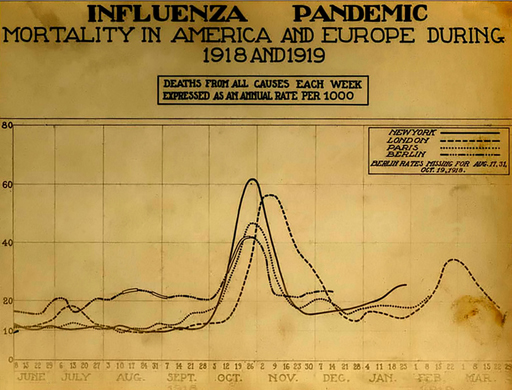

Similarly, the Spanish flu, which had touched almost every corner of the earth by the end of the war, would claim millions of victims among civilians and soldiers already weakened by hunger. Despite its name, the flu did not originate in Spain. A number of theories have been put forward, but evidence suggests that the disease may have originated in the American Midwest in early spring 1918, where it was spread between troops in military training camps. About half of the military deaths recorded by the US army were due to influenza.

By April 1918, the flu had been carried to various parts of Europe, including Spain, which initially led health authorities to believe that this was where it had originated. Three successive waves of the disease spread between spring 1918 and spring 1919, affecting nearly every inhabited area of the world. Highly contagious, the pandemic peaked towards the end of the war. It was easily transmitted by the movement of troops through densely packed areas of the front and major cities. Overall, it is estimated that around 2.5 to 5 per cent of the world’s population – somewhere between 50 and 100 million people – died as a result of the disease.