1.6 Indirect person-to-person transmission of pathogens

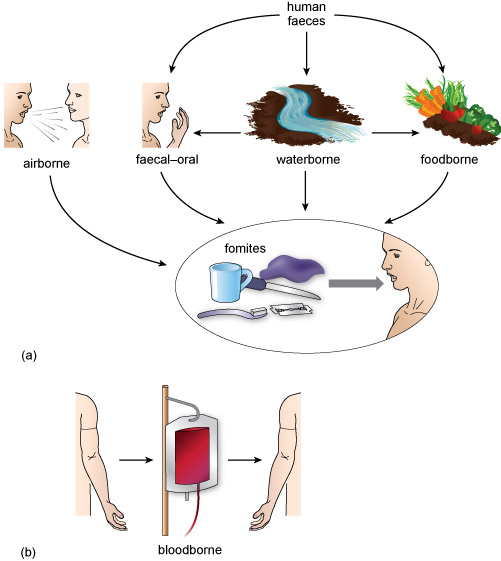

Indirect person-to-person transmission occurs when the original host sheds pathogens into the air, water, food or objects in the environment, which then infect someone else (Figure 6).

Most airborne infections are transmitted when a cough or sneeze expels fine droplets of water (known as an aerosol) containing millions of bacteria or viruses (Figure 7). The aerosol droplets may be inhaled by a susceptible person, or settle on surfaces where the pathogens contaminate hands, utensils, clothing, water or food, which are then touched or consumed by someone else.

Waterborne infections are particularly common in parts of the world where large numbers of people don’t have access to clean drinking water or safe disposal of sewage. Infected urine and faeces from humans and animals can wash into lakes and streams, where the pathogens multiply and reinfect people when they drink or bathe in contaminated water. Some pathogens (including the bacteria that cause cholera [koll-err-ah], a serious diarrhoeal disease) live naturally in environmental water sources, so they will always pose a threat to health.

Faecal–oral infections (‘faecal’ [fee-kal] and ‘faeces’ [fee-seez] refer to solid waste, or excrement) occur when pathogens from faeces enter the mouth (‘oral’ [orr-ahl]) and multiply in the gut. Transmission occurs when unclean hands, dirty cooking utensils or food contaminated by faeces enters the mouth. Flies can transfer pathogens from faeces to food via their feet. Contact with faeces is unavoidable when people are forced to defecate in the open because there is no sanitation. In these cases, people can get contaminated soil on their hands and the pathogens are easily transmitted from hand to mouth if there is no clean water or soap for handwashing.

Diarrhoeal diseases are often transmitted via the faecal–oral route, and some (e.g. cholera) are mainly waterborne. But they may also be due to foodborne infections caused by pathogens that originated in food components, for example, pathogenic bacteria in raw meat, eggs and on salad leaves.

Non-living objects in the environment, such as cups, spoons and door handles that people routinely touch, can also transmit infection and are known collectively as fomites [foh-mytz]. Clothing can also act as a fomite, which is why hospital doctors in the UK now rarely wear neckties that could drape across a patient during a medical examination and pick up infection that the next patient might acquire (Figure 8).

Can you identify the fomites in Figure 8 that could undermine infection prevention and control in this hospital?

In addition to the neckties worn by the two male doctors, all three doctors have stethoscopes, long-sleeved clothing, staff badges worn at waist height where they could brush against a patient, and the nurse is wearing a wristwatch. (If you go into a hospital in the UK nowadays, all staff must have their arms bare below the elbows, and wristwatches, rings and neckties are banned. Stethoscopes still touch a lot of patients on ward rounds and can’t be sterilised.)

Medical procedures can also transmit bloodborne infections; for example, before the transmission of HIV was understood, thousands of infections occurred from HIV-contaminated blood transfusions. Bloodborne pathogens can also spread via shared needles and syringes among people who inject illegal drugs, such as heroin.