2 Cell death and degeneration

Cell loss occurs in many tissues with age but the effects are particularly notable in tissues that have a limited capacity for regeneration, such as nerves in the CNS, the retina of the eye and the sensory cells of the inner ear.

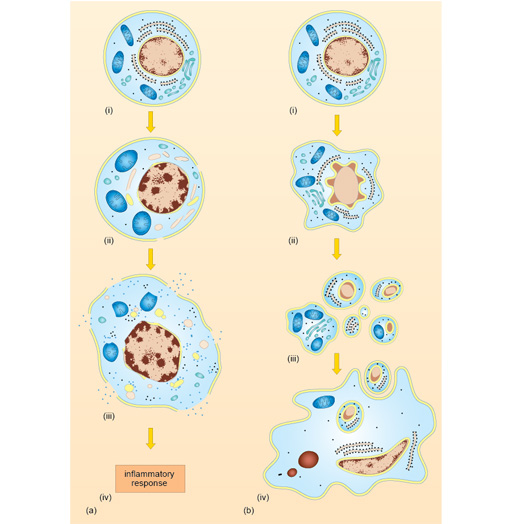

When cells die they do so in two main ways, by apoptosis or necrosis. This is illustrated in Figure 5.

Apoptosis

Apoptosis is programmed cell death; the cell dies as part of its normal programme of development, it may be lacking in growth factors or it may be instructed to die by cells of the immune system because it has become infected. Even pre-cancerous cells may be propelled into apoptosis by the normal cellular controls that check the development of tumours.

In all cases, apoptosis is a highly ordered process. If it occurs as part of a developmental process, it does not induce inflammation – the dead cells are quietly removed by phagocytes within the tissue. Therefore, it is often very difficult to identify apoptotic cells within tissues, since they are usually individual cells with small condensed nuclei and little cytoplasm.

Cell death in degenerative conditions (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease) appears to occur by apoptosis. Although the loss of individual cells is histologically undramatic, the cumulative loss of cells in such degenerative conditions can cause major loss of function in the affected tissue. Moreover, cell loss may be accompanied by the accumulation of products of tissue breakdown, which are histologically evident.

Necrosis

In contrast, necrosis is wholesale unregulated cell death, caused by lack of nutrients or infection.

For example, the failure of the blood supply to an organ (ischaemia) due to thrombosis will cause massive cell death due to lack of oxygen. A large area of cell death caused by ischaemia is called an infarction. Another example of cell necrosis is seen in severe viral infections with cytopathic viruses (e.g. polio).

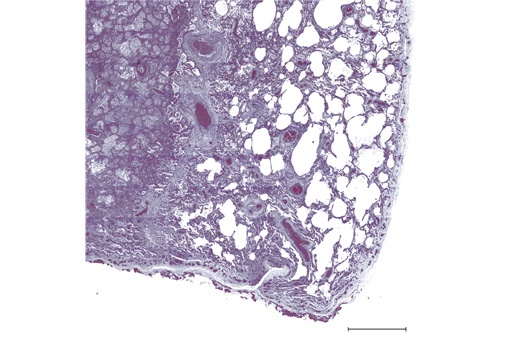

Necrosis is an uncontrolled process and the dying cells release their contents. Areas of necrosis are characterised by infiltration with inflammatory cells; macrophages and neutrophils enter the area over a number of days and weeks and clear the dead cells and associated cellular debris. Such large areas of cell loss and inflammation are frequently easily seen in pathological specimens, even without microscopic examination, as can be seen in the micrograph below.