1 Legislation: an introduction

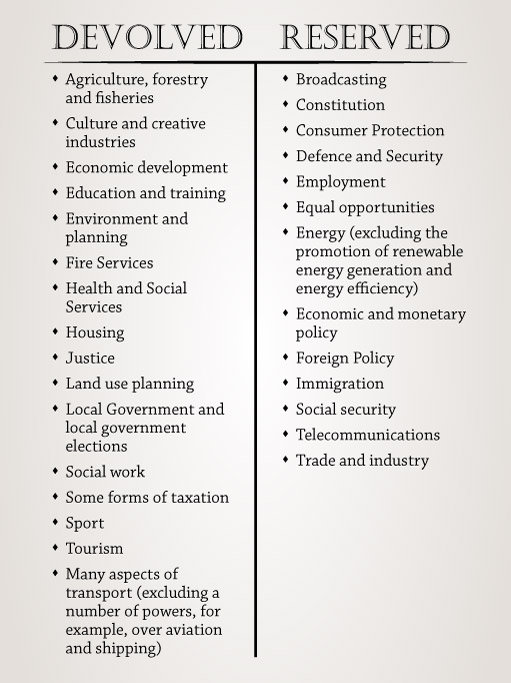

Both the Scottish and UK Parliaments create law that applies to Scotland. The Scottish Parliament can create laws in relation to devolved matters and the UK Parliament in relation to reserved matters. Through the use of legislative consent motions the Scottish Parliament can also agree to the UK Parliament making law for Scotland on devolved matters, for example, where a UK-wide approach is seen as sensible.

In general, legislation is the term given to law made by Parliament. It covers both primary legislation (Acts, which are also sometimes referred to as statutes) and subordinate legislation (which is sometimes referred to as delegated, subordinate or secondary legislation). Subordinate legislation is made and is created under power given in a primary Act. The primary Act sets out the scope of the powers being delegated and whom is entitled to make secondary legislation under the Act.

The term subordinate legislation tends to be used by the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Parliament (the Senedd). The terms secondary of delegated legislation tends to be used by the UK Parliament.

Many of the laws in Scotland have been created by way of legislation. This covers the following:

- Acts of the Scottish Parliament (on devolved matters)

- Subordinate legislation derived from powers delegated by the Scottish Parliament

- Acts of the UK Parliament

- Secondary legislation derived from powers delegated by the UK Parliament

- Acts of the old Scottish Parliament (the pre-1707 Parliament).

Both the Scottish and UK Parliaments are referred to as domestic sources of law. This course concentrates on these sources. Other sources of law, such as international Treaties, may have an impact on domestic legislation. But these are outside the scope of this course.

Whilst every care is taken when drafting legislation (whether Acts of Parliament or subordinate legislation) there are times when the words in an Act may not be clear. Activity 1 asks you to think about the meaning of words.

Activity 1 Meaning of words

Take a few moments to think about the following:

- What does read mean?

- What does book mean?

- What does change mean?

- What does order mean?

- What does left mean?

Comment

These words were chosen as they are homonyms or homographs. The same word, spelled or pronounced same way, can have a different meaning. The meaning is determined by the words that surround the word or the context in which it is spoken. Without a context it is difficult to determine the precise meaning.

- Read has a number of meanings. These are just three we identified:

- a.to look at and interpret letters or other information that is in a written format (read a book)

- b.to infer a meaning or significance (read into something, for example, the actions of a colleague or friend)

- c.to make a study of (I am reading law at university).

- Book has a number of meanings. These are just three we identified:

- a.a number of pages bound together

- b.to reserve something (I have booked a table at the restaurant)

- c.a collection of items, for example, a book of stamps.

- Change has a number of meanings. These are just three we identified:

- a.process of becoming something different (changing from a caterpillar to a butterfly, change of clothing)

- b.collection of small coins or money given back

- c.a transfer of some sort (you need to change trains at Inverness).

- Order has a number of meanings. These are just three we identified:

- a.some form of arrangement or organisation (for example the order of a marriage ceremony)

- b.a form of command

- c.a request for something, for example, ordering goods online.

- Left has a number of meanings. These are just three we identified:

- a.a form of direction, for example, take the next left

- b.something that remains, for example, there are three apples left

- c.a side of the body, for example, left hand.

You may have thought up other meanings (or looked them up online). This contextually dependent difference in meaning is just one of the challenges faced by those drafting legislation.

There are a number of factors which can lead to a word in legislation having an unclear meaning.

- A broad term – there may be words designed to cover several possibilities and it is left to the user to judge what situations fall within it.

- Ambiguity – a word may have two or more meanings and it may not be clear which meaning should be used.

- A drafting error – the Parliamentary Counsel who drafted the original Bill may have made an error that has not been noticed by Parliament. This is more likely to occur where a Bill has been amended several times during debates.

- Wording may be inadequate – there may be many ways in which the wording may be inadequate, for example, a printing error, or another error such as the use of a word with a wide meaning which is not defined.

- New developments – new technology may mean that an old Act of Parliament does not apparently cover present-day situations.

- Changes in the use of language – the meaning of words can change over the years.

- Certain words not used – the Parliamentary Counsel may refrain from using certain words that they regard as being implied. The problem here is that users may not realise that this is the case.

- Failure of legislation to cover a specific point – the legislation may have been drafted in detail, with the aim of trying to cover every possible contingency. Despite this, situations could arise which are not specifically covered. The question then is whether the court should interpret the legislation so as to include the situation which was omitted or whether they should limit the legislation to the precise points listed by Parliament.

Activity 2 now asks you to consider the challenges of interpreting wording where legislation has been poorly drafted through ambiguity or inadequate wording.

Activity 2 Interpreting legislation

Think about the following questions and make a note of your answer in the box below.

- Railway regulations state that a lookout should be provided for teams working on the other railway line ‘for the purposes of relaying or repairing it’. A and B were working on the railway line maintaining the rails. No look-out was provided as they were carrying out maintenance work. They were hit and killed by a train. Could the families of A and B claim compensation for their deaths?

- Would the phrase ‘any type of dog of the type known as the pit bull terrier’ include only the breed of pit bull terriers?

Comment

Both questions were based on the facts of actual cases. Many cases involve difficult circumstances where individuals have had recourse to the law to gain clarification of a situation or compensation for loss.

Question 1 was drawn from the facts of London and North Eastern Railway Company v Berriman [1946] 1 All ER 255. Mr Berriman was a railway worker who was hit and killed by a train while he was doing maintenance work. Regulations stated that a lookout should be provided for men working on the other railway line ‘for the purposes of relaying or repairing it’. Mr Berriman was maintaining the line. His widow tried to claim compensation for his death because the railway company had not provided a lookout man. The court ruled that the relevant regulation did not cover maintenance work and so Mrs Berriman’s claim failed. The court looked at the specific words in the regulation and was not prepared to look at any broad principle that the purpose of making a regulation that a lookout man should be provided was to protect those working on railway lines.

In London and North Eastern Railway Company differences in the reasoning between their Lordships (the term given to the judges hearing the case) emerged in the respective speeches of Lord Macmillan (at p. 295) and of Lord Wright (at p. 301), they reached opposite conclusions on the basis of what was the ‘fair and ordinary’ (Lord Macmillan) and the ‘natural and ordinary’ (Lord Wright) meaning of ‘repairing’ in Rule 9 of the Prevention of Accidents Rules 1902, and thought it necessary to refer to the Oxford English Dictionary, a will from 1577, Milton’s Paradise Lost and Dr. Johnson, to throw light on the meaning of repairing. You will explore why such differences in reasoning emerge in later sections.

In Question 1, applying the words ‘for the purposes of relaying or repairing it’ do not include maintaining it.

Question 2 was drawn from the facts of Brock v DPP [1993] 4 All ER 491. In Section 1 of the Dangerous Dogs Act 1991 (original unamended) there was a phrase ‘any dog of the type known as the pit bull terrier’. This led to a debate as to whether ‘type’ means the same as ‘breed’. In Brock, the court decided that ‘type’ had a wider meaning than ‘breed’ and it could cover dogs that were not pedigree pit bulls but which had a substantial number of characteristics of such a dog.

In Question 2 the words ‘any type of dog of the type known as the pit bull terrier’ are broader than breed. Type has a different meaning to breed.

A number of commission and committee reports have considered the interpretation of legislation. These include a joint report of the Scottish Law Commission and Law Commission in 1969 (which is considered in later sections) and The Renton Committee on the Preparation of Legislation in 1975. The Renton Committee divided complaints about legislation into four main headings, obscurity of language; over-elaboration of provisions; illogicality of structure and confusion arising from the amendment of existing provisions. You may recognise some of these criticisms if you have had to work with or read legislation.

When the meaning of the wording of legislation is unclear the judiciary may be required to determine the meaning. There are a number of cases where the courts have been asked to determine the meaning of a word or phrase in legislation. This leads to a number of interesting questions.

- How do the courts determine the intention of a Parliament?

- How can a consistent approach be achieved?

You explore the answers to these questions in later sections.

There are debates about the interpretation of legislation by the judiciary. Legislation is created by Parliament (whether Scottish or UK), a democratically elected body. When a case is brought to determine the meaning of a word or phrase in legislation a court presided over by one (or more) unelected individuals (judges) determines the meaning. Debates exist as to the relationship between the courts and judiciary and Parliament in these circumstances. Are judges making law when they determine the meaning of a word in legislation or are they merely confirming the intention of Parliament? Parliament can of course pass new legislation determining the meaning if it does not agree with the determination of meaning given in the court judgment.

The interpretation of legislation continues to be debated in academia and beyond. There have been a number of commissions and reports all of whom have made recommendations. Many still see the interpretation of legislation as a creative process which inevitably involves the judiciary in the process of creating law. Rules (the rules of statutory interpretation) which assist judges in interpreting legislation have evolved to establish some certainty and consistency. However, these rules have been produced over the centuries by judges themselves and Parliaments have played no role in their development.

Activity 3 asks you to consider how you would define a word in proposed legislation.

Activity 3 Words and legislation

Imagine you are part of a team drafting new legislation which is designed to bring peace to the countryside and regulate or stop activities such as off-roading, green-laning, paragliding, air ballooning, mountain biking and firework displays. The Bill on which the legislation will be based has been drafted following a number of fires which destroyed significant parts of moorland which were sites of special scientific interest and a number of incidents where animals have died as a result of being frightened by the noise and speed of vehicles. These have all been linked to leisure activities.

You have been asked to provide feedback to a colleague who has drafted a (fictitious) section which states:

The purpose of this Act is to bring peace and quiet to the countryside and prevent damage to property, persons and livestock and stop fire hazards.

Section 1: Everyone who uses the countryside is entitled to peace and quiet as they do so.

Section 2: Use of any vehicle in the countryside requires a special licence to be obtained from the Ministry of Vehicles.

Can you identify any possible issues with the wording of these sections?

Comment

There are a number of potential issues with the wording. These are the main ones we thought of:

- What does ‘peace and quiet’ mean? The countryside has wild animals and livestock. Would chirping birds disturb peace and quiet?

- The countryside is a working environment for farmers and others, all of whom use vehicles in one form or another. A provision intended to prevent what could be defined as leisure activities would impact on those working in the countryside and who perform vital roles in that countryside.

- There is a possible omission as vehicles are not included in the wording relating to prevention of damage.

You may have thought of others. The purpose of this activity was to illustrate how words can be used over which disputes may later arise because of their impact or interpretation.