2 Why film matters to the economy

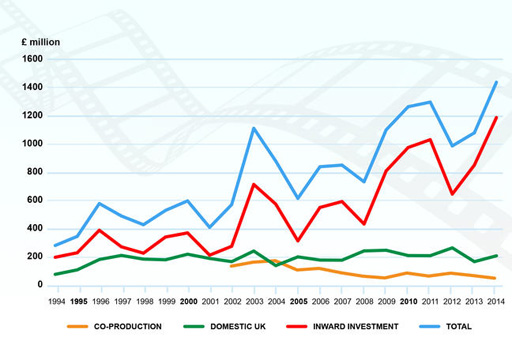

The graph below (BFI, 2014, p. 180) shows the amount of money spent in the UK on the production of feature films over a recent 20 year period.

You can see that UK spend of domestic UK films (the green line) has been reasonably constant over this example period. The UK makes many independent films that are identifiably British, such as Paddington, The Imitation Game, Mr. Turner, Pride, Philomena, I, Daniel Blake, God's Own Country, and The Favourite.

Many of these films perform well during awards season, obtaining BAFTAs and even US Academy awards. This is, naturally, a source of pride for the UK, and one of reasons that so many Hollywood stars are British.

Another increasingly important aspect of film and screen production is tourism. Film tourism – visiting a place that features in a film or television programme – is becoming ever more popular. Approximately £840 million of tourism spending by overseas visitors in 2013 was attributable to film-induced tourism (Olsberg SPI, 2015).

Film is often regarded as a driver of the other creative industries, in that it is high profile and often makes use of the highest design and creative skills. In the UK, film was the first creative industry to be supported by film incentives in recognition of its importance. Now fiscal incentives are available for high-value television, animation, games and for certain theatre productions.

So all is well for film in the UK?

Well, yes and no. Like in most other countries in Europe and around the world, American films take most of the money at the UK box office. UK independent films took only 10% of the UK box office takings in 2018 (We Are UK Film, 2018). There is no large British film production or distribution company based in the UK. American films distributed by American distributors take most of cinema-goers’ money and the profits belong to the American-based Hollywood majors (such as the so-called "Big Five" [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] ). Digital technology makes it possible for large global online firms to distribute worldwide, and again, most of these companies – Netflix, Amazon, iTunes/Apple – are US-based.

Does all this matter? Maybe. Maybe not, as long as audiences get the mass entertainment they want and there are some British films in our cinemas and opportunities for British talent.

However, it’s also worth bearing in mind the fragile balance between culture and industry components of film. The industry has a strong reliance on public funding and the extensive regulation framework that accompanies this. There is also a weak relation between the quality of a film and the price of a ticket (which remains stable regardless of production costs or demand).

In other words, films need to achieve critical mass to be profitable (so-called ‘blockbusters’) and to offset the costs of less lucrative productions. Risk has always been an inherent aspect of film-making, and for many years, the industry’s main focus has been on developing strategies of control. One way of dealing with risk is spreading out fixed costs across larger international markets.

Before you move on, take another look at the graph above. You’ll see that one line closely follows the line for total UK spend – inward investment.