3 Fats and oils

The obvious characteristics used to recognise fats and oils are that they have a slippery feel and do not dissolve in water.

We tend to use the term ‘fat’ to refer to those that are solid or semi-solid at room temperature (such as butter or lard). We use the word ‘oil’ for those that are liquid at room temperature. However, the word ‘fat’ on a food label refers to both.

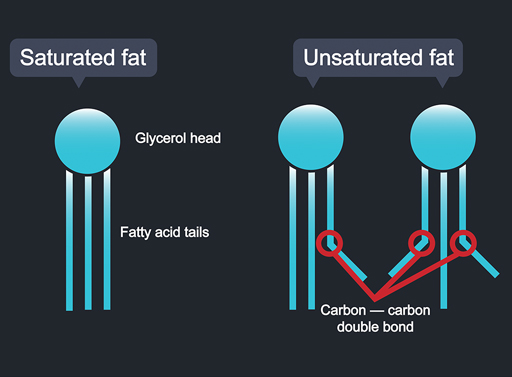

Molecules of the common fats in our diet, including oils, have a similar structure. They consist of a ‘head’ of glycerol with three fatty acid ‘tails’ joined to it (Figure 6). Of course, they are far too small to see. Each one is a few millionths of a millimetre long.

These fat molecules are technically called triacylglycerols – three tails (triacyl-) attached to a glycerol head. How solid a fat is depends on the fatty acid tails. Solid fats generally have straight tails. These are called saturated fats. The straight tails mean that the molecules can lie very neatly up against one another. There is also an attraction between the straight tails that keeps nearby fat molecules together. Fats composed of closely packed molecules like this tend to be solid at room temperature (for example, butter and lard).

If the tails are bent, the molecules end up jumbled. These are called unsaturated fats. Monounsaturated fats have tails with one bend in them. Polyunsaturated fats have two or more bends. When the molecules are not packed neatly, because of their bent tails, the fat tends to be a liquid at room temperature (for example, olive and rapeseed oil).

Both fats and oils are common in our diet. From animals, we get lard, butter and fat on meats such as steak, pork chops and bacon. From plants, we get olive oil, walnut oil, sunflower oil, and so on. You have probably noticed that fats from animals are generally solid, saturated fats (with straight tails) and ones from plants are generally unsaturated, liquid oils (with bent tails).