1 Basic elements of risk assessment

Risk assessment is the activity of understanding the extent to which potential events can affect the organisation’s ability to achieve its objectives.

In many situations, organisations do not have the resources to deal with all of the risks they face. By ranking them in relative order of importance, organisations can prioritise the treatment of risks. Risk assessment is the first step in prioritising risks.

Risk assessment can be both qualitative and quantitative, based on highly complex mathematical models or ‘gut feel’. Both approaches have their merits, but in its most basic form the aim is to understand what is the relative order or importance of the risks.

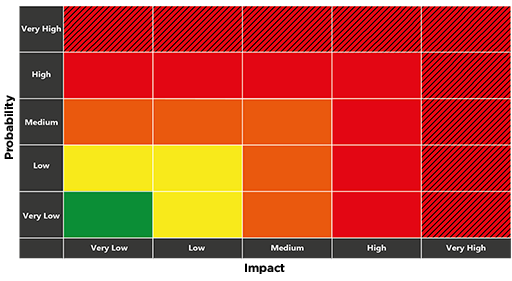

The most common approach to assess a risk uses two dimensions: impact and probability. This approach is usually displayed in a risk matrix (sometimes referred to as a Probability and Impact Diagram, or PID). It is also common practice to assign a value to each ‘cell’ in the risk matrix and this is commonly known as the risk score.

The risk impact(s) is the outcome of the consequences, which you examined in Session 3 when you looked at risk identification. For an organisation, risk impacts are often expressed in financial values, but may also be expressed in other values that are important to the organisation (e.g. health & safety, compliance, reputation). As an example, you may have identified a risk that a project may overrun with consequences that will cause late delivery and incur financial penalties. The impact would be the value of these financial penalties and a measure of the reputational impact of the late delivery.

The probability is the extent to which those impacts are likely to occur. The probability must be related to impacts otherwise the assessment is invalid; the two elements exist as one complete risk assessment.

It should be noted that other valid combinations of impact and probability may exist for the risk. To ensure correct risk assessment, organisations should set out rules defining how risks should be recorded. Some organisations use the ‘most probable’ approach, while others use ‘severe but plausible’. Whichever method is used, it must be consistent across the organisation to avoid potential confusion. Consider the simple example of the risk of fire. It may be equally valid to state that in the UK there are a large number of small fires, and therefore a ‘high’ probability of a small fire, but there are also a small number of very large fires and therefore a ‘low’ probability of a very large fire.

Some organisations may choose to look at additional measures, the most commonly used being:

- Timing of impact – when the risk could occur.

- Velocity (or speed of onset) – how quickly the risk could occur.

- Vulnerability – how susceptible the organisation is to the particular impact.

It is important to set out some prerequisites before moving forward. If you consider risk management as an isolated activity then the measures used to assess risk can be tailored specifically to that activity. However, having a bespoke way to assess risks in each individual area in an organisation with two or more activities is problematic. Look at a simple example, where Risk Managers compare three risks, each assessed on a different basis.

Transcript: Audio 1 Comparing risks

As shown in the example above, without a common approach to scoring, with everyone using the same scoring variables and common units of measure, it is practically impossible to undertake meaningful risk management at a company level.

As discussed in Session 2, it is therefore a prerequisite to set out, across an organisation, a set of common scoring variables and units of measure that everyone uses. Only by doing this is it possible to compare risks from one part of an organisation with risks from another part and thus maximise the return for the effort invested in risk management. You can see an example of this under the scoring scheme in the RMP you can download from Session 2 [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] .