1 Triggering the process of leaving the EU

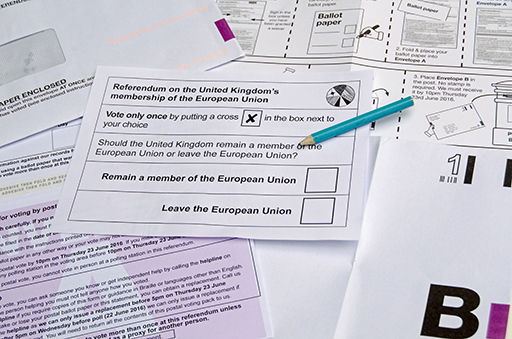

The apparently simple referendum decision flowed from a very straightforward question, namely ‘Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?’ But it was merely the first step into a tangle of legal (treaty-based) requirements and a series of complex negotiations. The formal process of leaving the EU was triggered by the UK government in March 2017 with the invocation of Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, which sets out the rights of member nations to leave the EU and spells out the procedure for doing so within a two-year timetable.

Following the referendum Parliament held a series of votes around the decision to trigger Article 50, which are explained in the following video by Richard Heffernan. Watch the video and think about how the referendum vote of an apparently divided country translated into such positive majorities in the parliamentary votes for leaving the EU in a House of Commons where most MPs campaigned for a Remain vote in the referendum.

Transcript: Brexit Open Minds Talk: What does Brexit tell us about Britain, 16th May, 2017. Richard Heffernan’s presentation

Despite this series of parliamentary votes, Theresa May (who became Prime Minister in the wake of David Cameron’s resignation) decided that she needed a stronger electoral mandate – a larger parliamentary majority – in her negotiations with the European Commission, so she brought forward a proposal to hold a general election. That election was held on 8 July 2017, with an outcome rather different from what the Prime Minister had expected. The Conservative Party failed to gain an overall majority and had to rely on the support (or at least acquiescence) of Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party to form a government. Incidentally, it also delivered a House of Commons in which the majority of MPs (in most parties, including the Conservative Party) had supported Remain in the referendum, although both the Conservative and Labour parties continued to express their commitment to withdrawing from the EU, in line with the outcome of the referendum.

In other words, over the course of a year, two sets of public votes took place, which highlighted the extent to which there continued to be significant political differences across the UK, and there continued to be some uncertainty about the precise path to be taken in leaving the EU.

But rather than discussing a series of possible electoral outcomes, the focus of this course is on exploring what the 2016 Brexit vote has to tell us about the UK as a political, social and economic space. Our purpose here is not to revisit all the debates nor to discuss whether the referendum decision was the right one. Nor is it to comb over the arguments that were made either in the course of the referendum or subsequent general election campaigns – important though such arguments undoubtedly are. Instead it is to reflect on some of the underlying features of the Brexit vote, to consider what they mean for the UK as a social and political formation in the twenty-first century. In other words, while the focus of the political debate around Brexit was on relations with Europe, in practice it was also about the nature of the political and social settlement within the UK – which is what you will explore here.

This course sets the experience of Brexit in the context of the UK’s reshaping and redefinition over recent decades. It first analyses Brexit as a symptom of the political, economic and social geography of the UK, particularly of its uneven development. This is expressed in the dominant position of London and South East England, and the political consequences of that dominance – or rather the dominance of the financial and business services industries located there. The divisions within the UK (within England as well as between England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) were reflected in the voting patterns of the 2016 referendum and the course reflects on the implications of this for the UK’s future as a multinational state.

The first step in doing this is to look a bit more closely at the voting patterns themselves.