1 Rich in resources, but low in growth

While many developing nations around the world are sitting on an abundance of minerals, fossil fuels and other natural resources, it has been well documented that they can struggle to effectively capitalise on these assets and translate them into stable economic growth and wider socio-economic development. In fact, the opposite is often true, that resource richness and dependency often result in economic stagnation, poor growth rates and rising inequality (Di John, 2011; Ross, 1999).

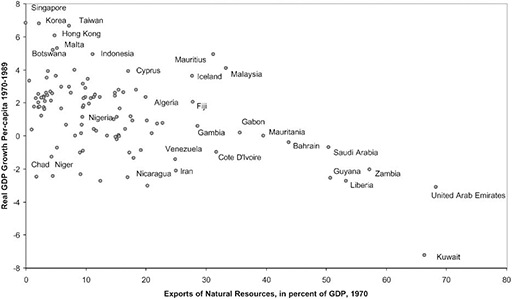

Jeffrey Sachs and Andrew Warner’s (1995) paper, ‘Natural resource abundance and economic growth’, is one of the most notable studies pointing out this trend. They examined natural resource-based exports as a percentage of GDP in 97 developing countries over a 20-year period (1970–89). What they found was a statistically significant negative relationship showing that economies with a high ratio of natural resource exports tended to have low growth rates.

This outcome could seem counterintuitive, as one would expect natural resource wealth to spell economic prosperity: generating high-levels of income through export and creating rents in the form of exploration and production licensing, for example. What is more puzzling is when you compare growth with resource-poor countries. Studies (such as Kurečić and Seba, 2016; Sachs and Warner, 1995; Shaxson, 2007) have shown that the economies of resource-poor countries frequently out-perform those that are resource-rich, most notably in the case of the Asian Tigers of the 1990s whose economies consistently grew at over 7 per cent per annum. In spite of a lack of natural resources, Taiwan and South Korea managed to rapidly industrialise.

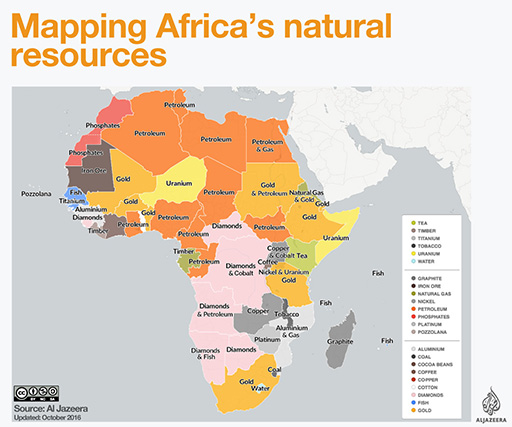

African economies, in particular, have been plagued by this problem. In 2016, natural resources accounted for 59 per cent of DR Congo’s GDP, Liberia 50 per cent and Sierra Leone 22 per cent (World Bank, 2016). Nigeria and Angola have relied on oil and gas rents for decades. In 1993, 63 per cent of Nigeria’s GDP was from oil alone. The general trend is that the exploitation of resources not only produces low economic growth but that it is linked to underdevelopment more broadly – high unemployment, low income, poor health and education provision and rising poverty and inequality. The benefits of revenue and rents fail to trickle down to the majority of citizens.

Yet, the continent abounds with natural resources and more are being found all of the time, which is why nations like China are increasingly looking to Africa to secure new supplies. According to Vines (2014): ‘Six of the top 10 global discoveries in the oil and gas sector in 2013 were made in Africa, with more than 500 companies currently exploring deposits there. There were nearly nine million barrels of crude oil produced daily in Africa last year, with more than 80% of it coming from established players such as Algeria, Angola and Nigeria’.

The negative link between resource abundance and poor growth is known as the ‘resource curse’. It has been explained in many ways and you will now turn to explore its characteristics, using the example of Nigeria’s oil sector, before going on to explore how the issue of politics, which is historically overlooked in resource curse analysis.