4.1 African agency

Is the perception that China, as a global superpower, can leverage this power to manipulate deals in its favour correct? Here, Giles Mohan outlines the argument that African countries’ politics is important for understanding how deals actually play out.

Transcript: Video 1

The rise of China, as you saw in the first session, has been impressive. However, China is a large and complex country with many different actors involved in Africa. As such it is unhelpful to talk in blanket terms about things like ‘Chinese firms’. Likewise, Africa is a large continent of multiple states, each one with its own complex history. So, a discussion of China-Africa relations is a shorthand which we have to use with caution.

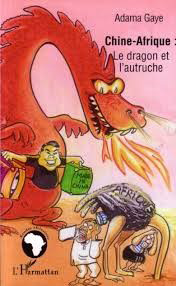

One of the upshots of thinking about ‘China’ and ‘Africa’ in homogenous ways is the tendency to assume that, given its ‘rising power’ status, China necessarily drives this engagement on its own terms. The corollary is that African actors are relatively, if not absolutely, powerless. Look at the cover image of a book on China-Africa published in 2006 around the time that China’s presence in Africa became an international talking point.

This book’s image of the fierce Chinese dragon bearing down on the African ostrich was typical of many representations of China’s engagement with the continent. The well-fed Chinese businessman riding in the dragon’s pouch brings lots of consumer goods ‘Made in China’ while the Africans are presented as ostriches, hiding from the onslaught. The result of such framings is that the agency of Africans was left out of the analysis.

In arguing for a greater consideration of African agency (see Mohan and Lampert, 2013) we need to avoid crudely reversing the analytical lens by suggesting African actors have limitless control over their destinies. Rather, African actors do exercise agency in multiple ways which is found in both formal, state-based politics as well as in wider social processes around trade, friendships, and many other relationships.

China’s re-entry into spheres of influence which have been the purview of the former European powers for two centuries or more has been one of the forces which have impelled a rethinking of African agency, largely because African states are able to triangulate between external actors, thereby giving them some space to manoeuvre. These spaces for manoeuvre include growing demand for strategic minerals and energy resources, the global ramifications of the post-9/11 securitisation process, and the rise of various ‘Southern’ actors which (according to some accounts) pose a threat to Western interests and which African states can exploit.

Ideas of ‘agency’ are all well and good, but how do we focus on this practically? In the next section you will use ideas of ‘political settlements’ to unpack how resource governance plays out in Africa.