6 China–Nigeria relations and oil

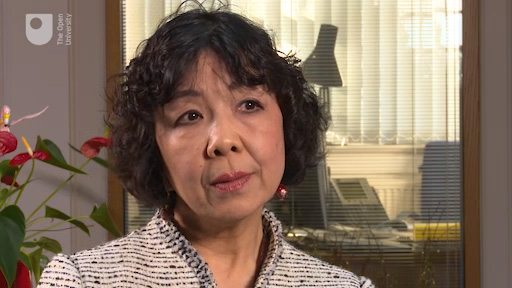

This section is about the impact of Nigeria’s domestic politics on Chinese investment in the country, the subject of the following video featuring Janet Liao.

Transcript: Video 4

China and Nigeria began formal diplomatic relations in 1971. This was at a time when Nigeria’s military regimes were receiving heavy criticism from Western powers and Nigeria was looking to the East to form new strategic ties. Since then, bilateral relations have strengthened to the point where China is now one of Nigeria’s most important trading partners. From around the early 2000s, Nigeria started to become a key source of oil for China’s expanding economy – in 2006 oil exports to China amounted $914m, but just two years later they had more than quadrupled to $4.4 bn (Abutu, 2012). The main strategy for investment in Nigeria has followed much the same lines as other African countries where Nigeria has used her oil to secure loans for grand infrastructure projects – the classic ‘oil for infrastructure deal’. Areas of construction have ranged from transport, such as the Abuja–Kaduna railway and the still unfinished Lagos Rail Mass Transit System; energy in the form of the Mambilla hydropower station; and industrial modernisation through areas such as the Lekki Free Trade Zone (Kafilah et al., 2017).

Despite these levels of investment, China has struggled to gain a foothold and secure stable, long lasting deals with Nigeria to leverage more direct investment in the oil and gas sector. The Chinese National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) and Sinopec (China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation) have bought into several offshore oil blocks and over the past several decades attempts have been made to expand ownership, for example during the 2007 oil licensing rounds the Obasanjo government offered Asian oil companies a Right of First Refusal. However, success has been limited. The main barrier most often put forward is that Western oil companies enjoy a stranglehold on the oil sector, having over 40 years’ more experience of operating in Nigeria than the Chinese, so they have a much greater competitive advantage. Figure 8 [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] shows a timeline mapping government-to-government deals involving oil between China and Nigeria since 2005. As you read through the detail see if you notice any patterns or interesting findings

Despite almost 20 years of China trying to negotiate a deal with successive Nigerian governments to invest in the oil and gas sector, a common feature of all of these government-to-government agreements is that not one has come to fruition.

Activity 2 Analysing political agency in Nigeria

Considering the ideas of African agency and political settlement theory you have been introduced to in this session, spend 10–15 minutes thinking about the timeline of Chinese investment deals in Nigeria as outlined in Figure 8.

What reasons can you think of for why these deals were unsuccessful?

Supporting text

As has been argued throughout this section, politics is incredibly important in shaping if and how investments are made and whether they bring development for African countries. However, politics is also a very complex business, and the politics of oil governance in Nigeria is particularly shrouded in mystery, so there is a lot of speculation surrounding the outcome of these deals. Two factors in particular need to be kept in mind:

- Western oil companies have a stranglehold on the sector, enjoying over six decades of dominance, making it difficult for the Chinese to gain a foothold.

- Building from this point, the oil sector is well developed and explored in Nigeria leaving very little room for new large investments attractive to the Chinese.

Others, however, maintain that the main barrier to securing these deals was a failure by the Chinese to understand how the politics of Nigeria’s oil governance works. Dynamics relating to both African Agency and Political Settlements (elite bargaining) can be seen playing out:

- Vines et al. (2009) analysed Chinese investment in the early 2000s. They attributed the breakdown of Chinese oil-for-infrastructure deals to the lack of Chinese understanding of the political machinations of the Obasanjo regime that was in power – ‘commitments to invest in the downstream and infrastructure projects failed to understand the political context of the time’ (Vines et al., 2009, p. vii). The decision to offer Asian oil companies the right of first refusal on bidding on the oil blocks was a subject of controversy and subsequently Obasanjo and his top elite were accused of driving the deal for personal gain.

- Playing into ideas of African agency, there is an argument that the Nigerian government and elites have decades of experience negotiating deals with Western governments and oil companies. Unlike many African oil producers engaging with the Chinese, they are not new players and so have used this knowledge and experience to bargain harder. The failure of Yar’Adua to carry forward the oil-for-infrastructure deal struck under the Obasanjo regime has been attributed to falling global oil prices, for example. It meant that the number of barrels originally negotiated in return for investment were now worth significantly less. Yar’Adua was supposedly unwilling to compromise on the terms because he knew there were many other companies looking to invest.

- Umejei (2013) looked at the subsequent Yar’Adua negotiations and concluded that when the delegation arrived in Beijing they discovered that the previous administration had not concluded the deal as the Chinese had thought. Also, a lot of the figures were not adding up, which led Umejei to speculate that corrupt practices may have been a cause of the deal collapsing.

- Mthembu-Salter (2009) highlights how the electoral cycle trumps any business deal: ‘…the termination of the “oil for infrastructure” approach by the current Nigerian government demonstrates an incompatibility between this model and the Nigerian electoral cycle, which is designed to alternate rule every ten years between northern Muslim and southern Christian elites.’

Whatever the underlying reasons, based on observations from the timeline, it would be reasonable to infer that the politics and interests of different administrations has impacted, and negatively so, on the ability of the two countries to strike lasting investment deals.