6 Political risk and the ‘Genocide Olympics’

Earlier in this session you were introduced to the idea of political risk, and a landmark event in the evolution of China’s approach to international investment and its calculation of political risk came in the run up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics. As Moreira’s overview of Chinese oil investment strategies noted, China often relied on inter-personal relations as its main way of managing risk. However, Sudan – and events in Darfur in particular - became a major test case for China regarding its engagement with ‘pariah’ political regimes. Some of this outcry against China was part of a wider ‘China bashing’ discourse (Ramirez and Rong 2012) that was keen to accuse China, as a communist country, of riding roughshod over human rights. The upshot of China’s handling of the Darfur situation was a much more acute sense of political risk and how to manage it.

In Video 4, Dr Liao reflects on this important period in the history of Chinese-Sudanese relations.

Transcript: Video 4 How geopolitical events impact on oil investment

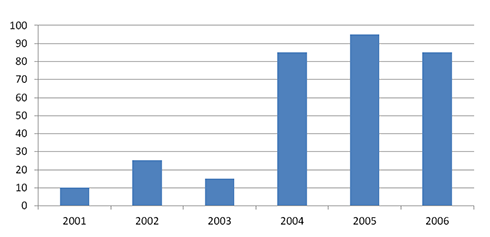

The overview of Sudan’s political history and the timeline given in this session show that the Darfur crisis was intensifying in 2007. This was a period when Chinese NOCs had become well-established in the country and the diplomatic and trade relations between China and Sudan were strong. With China’s economic rise came a desire to be seen as global player, and hosting the Olympics is one way that countries can ‘market’ themselves as responsible actors on the world stage. The Tiananmen Square protests had previously sent a signal that China was closed and still highly authoritarian, but the Olympics were a platform to show the world how much China had changed, becoming more open and friendlier toward the international community. But with the spotlight intensifying in the run-up to the Beijing games, China was accused of colluding with the Khartoum regime in supporting the suppression of Darfur by selling arms to Sudan. Figure 3 shows the importance of Chinese arm imports to Sudan, which were almost as much as the value of Sudan’s own exports in the 2004–2006 period.

Activity 4

Read this New York Times news story [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] from early 2008, around 6 months before the Beijing Olympics. As you read it, consider the range of political actors involved. Having read it, go back to the timeline and find out what China’s response was.

Discussion

The New York Times article reveals the vast array of political interests at play in Sudan during the period in the run-up to the Beijing Olympics. In Sudan there is the al-Bashir government in Khartoum, but also rebels in Darfur and the Janjaweed militias. The United Nations is also very active, notably through a security deployment in Darfur, but the Sudanese government had barred troops from Sweden, Norway, Nepal and Thailand. The US government is involved, as are Chinese officials. On top of this are international civil society organisations. Amnesty International was commenting on the crisis and the ‘Genocide Olympics’ campaign was an internationally networked effort of celebrities and civil society actors. The article also mentions how the Chinese seemed to prefer ‘quiet diplomacy’ and once pressure was placed on them they began to help find a solution. One such solution was, as the timeline showed, the appointment of Liu Guijin as the special representative to Darfur. Liu was an experienced diplomat and had been based in Africa for many years so was a very shrewd choice. His interventions helped smooth things over and the Olympics passed successfully. The longer-term implications were that China became much more aware of the risks associated with domestic political forces, as well as the power of international public opinion.