2.3 Determinants of linkage development

Many factors may affect linkage development from resource extraction in the local economy. Here you can explore some of the key factors that can either promote or inhibit linkage development from resource extraction in developing country contexts.

Geological location, technology and resource specificity

All extractive resources are unique to the location in which they are found. This means that the technology, skill and knowledge needed for efficient exploitation of the resource have to be locally applied on site and this provides an opportunity to draw on local knowledge and skills. However, in developing economies where skills, knowledge and technical capacity may be undeveloped or non-existent, because the resource production activity is relatively new to the locality, indigenous businesses may not have the necessary capacity to take advantage of these outsourcing opportunities. This creates the entry space for foreign firms to bring in foreign capital, expertise and technology and also further outsource to other foreign suppliers.

Generally, therefore, whether local linkages will develop depends on whether the array of skills (both specialised and general) and capacity required for effective resource production and input supply is available locally. The level of education determines whether local people are employed over skilled expatriates. In most developing resource economies, there is not only a skills gap but, even where the skills exist, the quality of locally-available skills often does not meet international standards. For effective linkage development, skills have to be grown and harnessed effectively. Also, supporting frameworks and institutions have to be developed to enhance the technological development and innovation of local suppliers, especially as technological intensity of linkages increases.

The technology and capital requirement for the resource extraction is also intrinsically dependent on the geological location of the resource find and determines whether local linkages can be easily developed. For example, the technical expertise and capital required for offshore oil production is relatively high, compared to onshore oil production. The Chinese NOCs largely developed onshore capabilities, so, as they have entered offshore fields they have partnered with Western IOCs who have the deep-water expertise.

A closely related point is that the highly capital-intensive nature of resource extraction can also lead to scale and technological barriers. Hence, in cases where there is no developed industrial sector, local linkages will be limited. However, there would usually be some areas along the value chain that require relatively low levels of technological expertise and with low barriers to entry, which indigenous suppliers could always take advantage of. This might include, for example, security services for oil facilities or supplying accounting services.

Ownership

It is widely believed that locally-owned lead firms are more committed to local development and may organise their extraction activities in ways that promote linkage development more than foreign lead firms. There is also the general belief that the nationality of the foreign lead firm may also influence linkage development. For example, if the lead firm is from a country with highly developed equity markets where patient capital (i.e. long term) is available and government support is high, then such a lead firm may be predisposed to have more patience for developing the capacity of local suppliers.

In another vein, it is argued that lead firms from the global north face a lot of pressures from civil society in their countries to adopt CSR that promotes backward linkage development by investing in intensive local supply chains to spread the benefits of resource production to communities in resource-producing areas. However, in areas where civil society pressures are not profound or do not exist, and where the host country does not have a robust policy or legal framework to promote linkage development, the lead firms may be less inclined to promote linkage development.

Infrastructure

Infrastructure here can take several forms and includes road and rail transport, utilities and telecommunication, as well as social forms which reflect the efficiency of the administrative and regulatory framework supporting the productive sector. For example, road and rail infrastructure have the potential to reduce logistics costs for processors and suppliers.

Policy

Policy has proven to be a critical factor in linkage development. A key policy instrument widely used in the resource sector is referred to as local content policy, which is usually backed by legislation and sets some specific targets for localising employment in the resource sector as well as widening and deepening local supply chains for the resource sector. For such policies to be effective, the targets and implementation strategies should be realistic and the policy also needs to align with other government policies. It should also be recognised that government is not the only actor in the policy environment, hence successful policy development and implementation requires an alignment of visions and capabilities between the state, the private sector and even civil society organisations. In particular, indigenous suppliers’ perception of the opportunity cost of responding to the incentives created by local content policy is critical for effective localisation of the resource supply chains and linkage development.

Time

While all the above-mentioned factors are important for localisation and linkage development to happen, it is also important to understand that linkage development takes time. In general, a country that has exploited oil for longer would have achieved more localisation and linkage development than one whose oil industry is young.

Activity 1 Ghana’s petroleum legislation

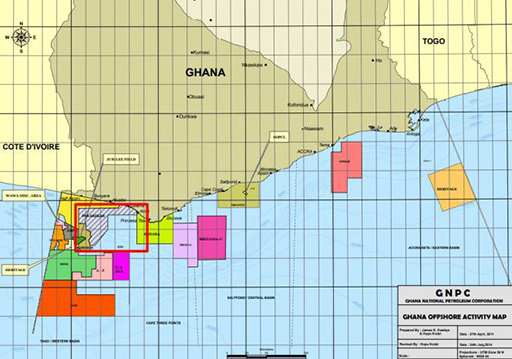

For the latter part of the twentieth century Ghana’s oil industry was confined to small on-shore oil fields. It had long been suspected that there were sizeable oil reserves located off-shore.

In 2007 these suspicions were confirmed and with the expertise and capital from a number of IOCs Ghana started producing oil just three years later. The speed of production meant that the legislation and institutions needed to effectively govern oil for the country’s development lagged behind, but from 2011 they began to be put in place (Mohan and Asante, 2015). The most important for this discussion of linkages and local content were the Petroleum Revenue Management Act (Act 815 of 2011) and the Local Content and Local Participation Bill (L.I 2204 of 2013). These and the other pieces of legislation are available at: http://www.petrocom.gov.gh/ laws-regulations/ [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] .

As these laws are quite long and in technical language, summaries have been provided below.

These pieces of legislation set out the Ghanaian state’s vision for how to capitalise on the benefits from its oil. As you read the summary discussions make notes on the main ways that the oil economy might benefit Ghana’s development.

Discussion

The following is a list of 11 potential developmental outcomes identified from the legislation. How does your list compare?

- At the most abstract level Ghana’s Constitution vests the control of resources in the hands of the President who should then distribute them in a way that benefits the nation.

- A proportion of the revenue is allocated to the ABFA which is ring-fenced for investment in priority sectors that directly impact upon development like agriculture, housing and healthcare.

- The law prevents this revenue being spread too thinly and so undermining its impact

- In the last few cycles of ABFA spending the priorities have been roads and other transport infrastructure, agriculture, health, and oil and gas capacity building.

- The ABFA can also act as collateral for other loans, which could also go into productive investment. This happened with a loan from the Chinese that helped build gas processing infrastructure.

- The GHF builds up a long-term investment fund that can be used when the oil runs out.

- The GSF helps cushion the economy from shocks which helps bring much-needed macro-economic stability.

- The Local Content Bill encourages employment for Ghanaians in the petroleum industry.

- Ghanaian firms have a minimum stake in joint ventures with international companies and so can benefit from profits that are generated.

- It encourages supply chains in Ghana so that more of the ‘spend’ stays in the country.

- The IOCs can transfer knowledge and skills to Ghanaians.