3 The anatomy of argument maps

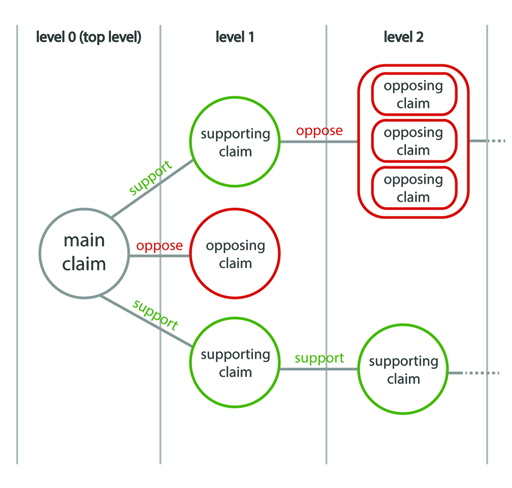

In Activity 2 you saw that a claim can itself be supported or opposed by a further claim. And that claim can, in turn, be supported or opposed by other claims. In summary, an argument map can have three types of claim: a main claim, supporting claims and opposing claims. Whereas there is only one main claim, there can be any number of supporting and opposing claims.

You can think of the claims in an argument map as living on different levels. The main claim lives on Level 0. Claims that support or oppose it are on Level 1. On Level 2, you find claims that, in turn, support the claims at Level 1. And so on. An argument map can have any number of levels. This idea is illustrated in Figure 7.