2 Communication skills

One of the foundational elements in social work is the ability for the social worker to have good communication skills. Seden (2005, p. 20) suggests that verbal and non-verbal methods in social work communication are used to:

- transmit and share information

- establish relationships

- exchange ideas and perceptions

- create change

- exchange attitudes, values and beliefs

- achieve service user and practitioner goals.

However, Seden points out that for effective communication, social workers need to be sensitive to the other person, their understandings, their interactions and their social context. All of us as individuals have our unique set of preconceptions, prejudices and cultural conditioning. Consequently, no one can claim to be wholly neutral in any particular encounter. The process of developing self-awareness and conscious control of our interpretations and reflections is, therefore, a primary requirement and ongoing professional responsibility for all people working in the helping professions, including social work.

Social workers are frequently involved in interviewing service users, other professionals and family members. Interviews will almost always have pre-existing objectives, and a skilled interviewer will have at their disposal a range of methods and responses that are practised and developed to maximise the relevance and quality of the interview content, as well as enabling the person being interviewed to feel as at ease and as safe as possible in each situation. These skills include listening and paying attention to the detail as well as to the themes or difficult to articulate elements; responding in a way that indicates to the other person that they have been accurately understood; and questioning, in ways that are respectful and wherever possible are in line with the service user’s wishes and needs. Where it is evident that there are barriers present or emerging that may be preventing effective communication, it is the responsibility of the social worker to anticipate and manage these barriers and to minimise their negative effects.

Seden (2005, p. 14) identifies some of the communication skills required by social workers, as including the following:

- acceptance

- active listening

- attention giving

- challenging

- confronting

- genuineness

- goal setting

- immediacy

- linking ideas

- listening

- paraphrasing

- problem-solving

- appropriate prompts

- questioning and exploring

- reflecting back

- summarising

- use of empathy

- working on defences.

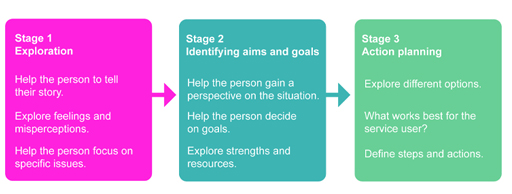

Gerard Egan (1994) suggests that generally, although never in a rigid or an artificial way, communication can be improved by facing the other person squarely, maintaining an open posture, leaning slightly towards them, maintaining eye contact, and trying to be relaxed. In his book The Skilled Helper, Egan presents a three-stage model for communicating effectively in a helping context. These stages are: Exploration; Identifying aims and goals; and Action planning. The three stages are shown in the diagram below:

Egan highlights the need for Active Listening, requiring the helper to attend to the service user’s non-verbal and verbal communications, paying attention not only to their words, but also to their body language, facial expressions and tone of voice. It is also important to convey empathy and acceptance, resisting any attempts to express your views or conclusions at too early a stage. Rather, it is important to gently paraphrase and summarise the service user’s account to verify your own understanding, reflecting back and seeking clarification in a measured and sensitive way. This clarification will include helping to identify the aims and goals of the service user, as well as considering options for whether or how these goals may be achieved.

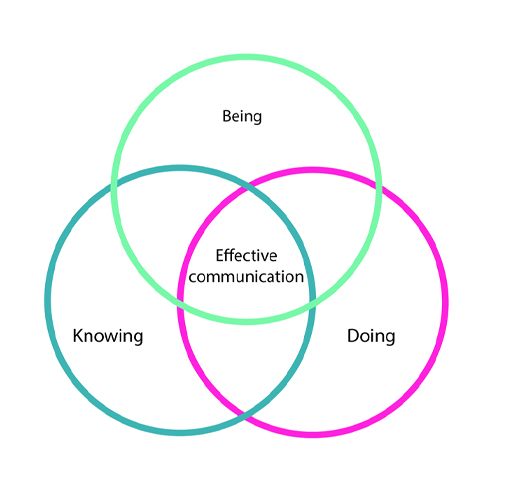

In addition, Lefevere (2010, p. 61) argues that effective communication not only requires the person in a helping capacity to have a good range of practical and theoretical knowledge, but they must also have good self-awareness and self-knowledge. This combination of skills is identified by Lefevere as the ‘knowing-being-doing’ model.