9 Language and power

Language, as the basis of interpersonal and social communication, is so ingrained in our day-to-day life that it tends to be taken for granted (Thompson, 2011). Cultural and linguistic studies of language, however, reveal that language is neither straightforward nor neutral. Thompson summarises the issues like this:

Language is closely associated with power, with the way we make sense of our lives and of the social world, and even how we make sense of ourselves – that is, our identity … Language can be used to solve problems, to build positive and constructive relationships, to inspire and motivate and to liberate. However, it can also be used to create problems as well as solve them, to incite hatred and to create great pain and suffering.

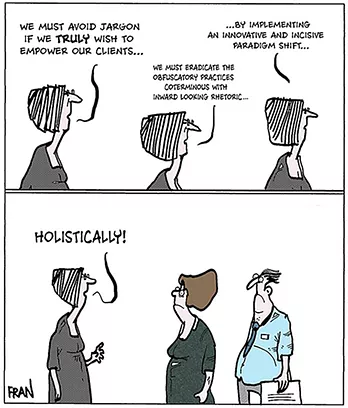

Vojak (2009) argues that organisational and professional language used to talk about people, their situations and services can have stigmatising effects and perpetuate inequality. It is important therefore for social workers to understand the relationship between language and social justice, so that they can take a more empowering approach. In some instances, social workers may need to help service users understand, for example, legal or medical terms that can cause confusion or anxiety. The same applies to social work ‘jargon’ – words such as ‘dysfunctional’ and ‘chaotic’ which can produce negative and labelling effects. Even the term ‘mum’, used in place of a parent’s name, can sound very diminishing.

Social work practice can itself be shaped and constrained by the power of official language. Gregory and Holloway (2005, p. 46) point to the adoption of managerialist concepts and terminology since the 1990s. Social work discourse is now dominated by ‘a strong emphasis on managing “outcomes” – a word never before connected with the welfare services’, along with ‘[the] language of risk management and the language of consumerism’. At ground level, social work practitioners may need to take a critical stance about the use of pathologising language. For example, Duffy (2016) urges against the use of ageist professional shorthand (such as ‘frequent flyer’ or ‘bed blocker’) when working with older people.