4 Participatory budgeting

Originating in Brazil, participatory budgeting is a form of community stakeholder engagement relating specifically to the management of public finances. Defined by Wampler (2007, p. 21) as ‘a decision-making process through which citizens deliberate and negotiate over the distribution of public resources’, participatory budgeting processes are unique to the extent that they engage non-elected members of society in financial processes for the benefit of all members of society.

Wampler (2007, pp. 21-22) argues that participatory budgeting is effective, and consequently important, as it addresses the needs in a positive way of both the governments and the citizens in those areas where it has been practiced. Participatory budgeting can consequently play a role in enhancing not just the performance of state institutions but also and the quality of democracy and democratic involvement. In particular, participatory budgeting

helps improve state performance through a series of institutional rules that constrain and check the prerogatives of the municipal government while creating increased opportunities for citizens to engage in public policy debates. It helps enhance the quality of democracy by encouraging the direct participation of citizens in open and public debates, which helps increase their knowledge of public affairs. (Wampler, 2007, pp. 21-22)

What forms does participatory budgeting take?

Since its emergence, various studies have examined the forms that participatory budgeting can take in practice. A study by the Public Policy Institute for Wales (Williams et al., 2017) summarised the key forms of dimensions of participatory budgeting as follows:

| Level of participation | What involvement means in terms of degree of control (e.g. inputting views versus making the decisions) and whether PB is used as a tool for empowering participants or as a consultation mechanism with little change in power dynamics and influence. |

| Who is involved | Whether those who participate are, for example, citizens, representative groups, NGOs, or private companies. |

| At what stage are participants involved | Broadly, there are four stages, all of which could involve participants:

|

| Method of involvement | The two broad categories involve:

|

| Scale | PB has been implemented at different spatial scales (e.g. national, local, neighborhood); with different types and levels of budget (e.g. small scale grant allocation, or setting priorities for, in some cases multi-million pound, mainstream budgets) and with different foci (e.g. making choices within a policy or thematic area, such as health, or across themes but within a geographical area). |

| Whether and to what extent PB is redistributive |

|

Examples of participatory budgeting

PB in Scotland

PB in Scotland has been increasing over the last few years and is viewed by the Scottish Government as a way of increasing citizen engagement in decision making. This ambition was developed into policy through the Community Empowerment Act 2015, which aimed (amongst other things) to strengthen citizens’ voices in the decisions and services that matter most to them. To deliver this, the Scottish Government created the Community Choices fund (£1.5 million) dedicated to funding and supporting PB. This national budget is delivered locally and has a redistributive element with the funding targeted particularly in deprived areas. There has also been a broader commitment to mainstreaming PB practice as by 2021 1% of all local government budgets will be allocated in this way. In October 2018, a PB festival was held to raise awareness and strengthen the implementation of PB processes locally.

Example of participatory budgeting

PB in Northern Ireland

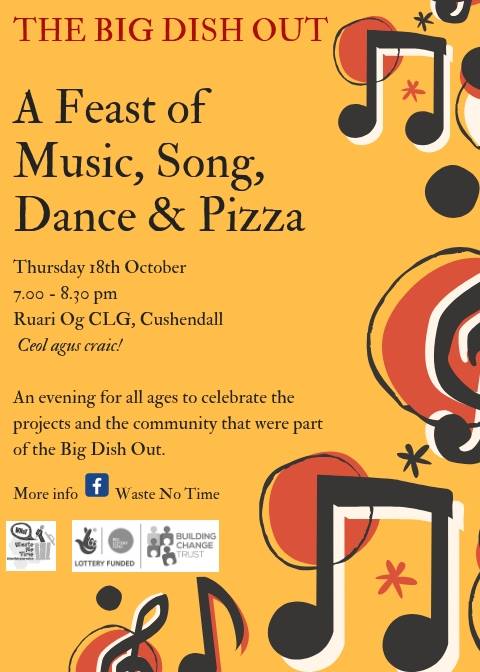

The implementation of PB processes across NI has been modest; however, the ‘The Big Dish Out’ represents a local example that was delivered by the ‘Waste No Time Team’ with support from the Causeway Coast and Glens local council. After a lengthy engagement period which helped to promote and secure support for the process, two PB events took place with participation from Cross Glebe Community Association and a number of local groups in the Cushendall area. The agreed bid pot of £6,000 attracted bids from 32 different projects, which was eventually split 10 ways to support local projects with various objectives that included tackling isolation, improving community safety and promoting inter-generational activity. Although each project only received £300, the Big Dish Out provided local people with a greater sense of ownership as they were able to decide what issues were important to them and as a result resources were allocated with full community backing.