2.1 Forms of justice

Over the course of history, the idea of justice has been understood and defined in many different ways. This section considers some of the key forms of justice which still influence how we understand justice today.

Distributive and corrective justice

Writing in the fourth century BC, the Greek philosopher Aristotle was responsible for some of the earliest views on justice.

Aristotle believed that a just law was one that both encouraged individual freedom and enabled people to live peacefully. From society’s perspective, key to this was allowing people to fulfil themselves in society.

In considering perspectives on justice, Aristotle distinguished between what he saw as the two key forms: distributive justice and corrective justice.

Distributive vs corrective justice

At its simplest, distributive justice focuses on how things such as rights, goods and well-being should be distributed amongst people.

The core idea of distributive justice, according to Aristotle, is that of ‘treating equals equally’. Yet what exactly does this mean. Who, for example, are the relevant equals? And what is actually involved in treating people equally?

On the other hand, corrective justice is about giving someone either what they deserve or have a right to. In a legal sense, this can relate to punishment due for an offence which has been committed, or – conversely – the redress someone is due for a wrong suffered.

Natural justice

The ancient Roman’s took a slightly different perspective, arguing that rather than being the product of human society, basic legal principles are derived from nature. The underpinnings of this view still exist today in the form of natural justice. Key principles of natural justice hold that each person is entitled to a fair trial and that a judge must be free from bias. These principles – or at least the assumptions underpinning them – are still commonly found in discussions of rights and justice today.

Substantive justice

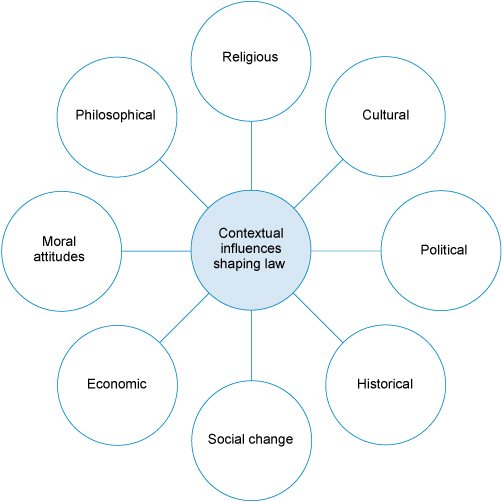

This is concerned with the content of the law. The legal principles created by relevant legislative bodies and the courts need to be regarded as ‘just’. What is considered to be just in these circumstances is influenced by a range of social and contextual factors, many of which are captured in this diagram:

Substantive vs formal justice

Beyond more philosophical perspectives, definitions of justice are also quite practical in nature. In this regard, it can be useful to distinguish between substantive and formal aspects of justice.

The moral and cultural values of the society in which the law is created are especially influential in determining whether any given law is regarded as just. Where a law is considered to be unjust the consequences for social order can be potentially far reaching, up to and including social unrest.

In contrast, formal justice is concerned with ensuring that legal principles are applied in a way which is fair. This invariably involves treating people in a similar situation in the same way: like cases should be treated alike. It is important that judges are unbiased when they hear cases, and that the same rules of procedure are applied to everyone in the same way. It is also important that regulatory frameworks such as health and safety laws, planning laws and financial services laws operate and are applied in a way that is fair and consistent.

The European Convention on Human Rights

Since 1950 the UK has been a signatory to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The ECHR is an international treaty signed by members of the Council of Europe and is, consequently, separate and unrelated to Brexit and the UK’s departure from the European Union. Being a signatory to the ECHR, means that the UK along with other countries, is ‘committed to upholding certain fundamental rights, such as the right to life, the right to a fair trial, and the right to freedom of expression’ (Dawson, 2019).

Activity 2 Types of justice

Reflect on the types of justice described in the animation below.

Which one do you feel is most relevant in a modern world?

Transcript

[MUSIC PLAYING]

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Discussion

Over the course of history there have been many different approaches to and interpretations of justice. Those forms of justice found in modern societies are often a reflection of a society’s history, but may also reflect efforts to adapt to meet the changing needs of the modern world. Ultimately, it is about recognising the value and importance of justice and the need to recognise the rights of every human as enshrined in human rights legislation and conventions.