Professional football is a business to the extent that it involves investment (in players, stadium, customer service, etc.) and a return (from ticket prices, merchandise, sponsorship and broadcast rights). Professional football officially started in England in 1885 (baseball in the US had already been operating professionally since 1871), and while technology has changed, the fundamentals of the business model have not. Clubs must risk money by hiring players in the expectation of success in competition – league and cup – which will in turn attract fans. Successful clubs can grow by improving the quality of their squad and by enlarging their stadium. Unsuccessful teams risk financial failure as revenues fail to match promised expenditures.

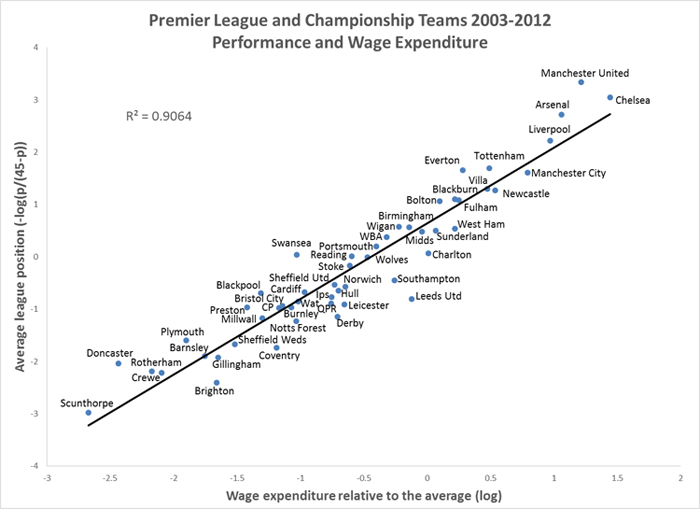

The operation of the market in players and clubs can be illustrated with two simple comparisons. The first (Figure 1) relates the average league position of teams appearing in the top two English divisions over a decade to their average wage spending, expressed in proportion to the average wage spending of all clubs. The figure shows that wage spending is highly correlated with league position over time. The ‘R2’ is a statistic which measures the percentage of variation in league position that is captured by wage spending, so a value of 90% is a very strong signal of a significant relationship between wages and league standing. Likewise, the relationship between average league position and revenues, again expressed relative to the average of all other clubs, is very close indeed. Over a decade the R2 is again just over 90%. These correlations need explanation – a theory of how the market works – in order to be understood.

Figure 1

Figure 1

The football business market: Players and clubs

We can observe that clubs compete aggressively to hire players – there is an active transfer market with thousands of transactions a year worldwide (globalisation has had a huge impact on the football business). Player characteristics are easily observed before and after they are hired, and so wages can be expected to accurately reflect player ‘productivity’ (clubs would not choose to pay more than they could afford, and players would ask for a transfer if paid less than they were worth). And so in football, clubs usually get what they pay for. Not that this relationship is perfect – random factors (good and bad luck) make this relationship much less reliable in the short term – players get injured, and have runs of unexpectedly good and bad form. But over time good and bad luck tend to cancel each other out, and so you get what you pay for.

Owners of American teams are often characterised as profit-maximisers who view professional sport as a business for making money.

There is a market for clubs too. While there is a myth of eternal loyalty on the part of fans, this is true only for a small minority. Most fans tend to follow a team more intensively the more successful it is. (In 2003 Borland and MacDonald conducted a survey on the demand for sport.) Teams that are relegated lose large numbers of fans. That is why revenue is so closely related to league position – poor performance on the pitch means fewer tickets sold, less merchandising, less sponsorship and broadcast income. Because the football business is so competitive – so many teams competing for fans, and with the ever-present threat of relegation, most clubs are only just able to balance income and expenditure. (financial information on English clubs is available Companies House website and can be accessed free of charge.)

Against this background it is perhaps not surprising that insolvency is a common problem in football. Significant underperformance (either in terms of performance based on wages, or of revenues based on performance) will mean that a club cannot balance its book. In the last 30 years there have been about 70 cases of insolvency involving English clubs in the top four divisions. But this is a pan-European problem. According to the most recent survey of European football club finances by UEFA (UEFA, 2012), 63% of top division clubs in Europe reported an operating loss, 55% reported a net loss, 38% reported negative net equity and auditors raised ‘going concern’ doubts in 16% of cases. This is also not a recent problem: a British government report by Sir Norman Chester in 1968 expressed concern that football clubs might become bankrupt en masse. In 1983 another report by Chester suggested that without fundamental reform English football might collapse. (Many people believe that the turning point in English football, following 50 years of post-war decline, came after the Hillsborough disaster and the Taylor Report of 1989, which mandated all-seater stadiums and triggered an investment boom. But in fact attendance at English league football started to revive from 1985 onwards.) However, despite frequent financial failure, clubs are almost always bailed out by fans and wealthy investors – it is hard to think of one European club of any significance that has disappeared in the last 50 years, despite frequent financial crises. (See Szymanski (2017) for a detailed analysis of insolvency in English football.)

In reality football clubs are more than just businesses – they are community assets. Local government usually will not allow a stadium to be sold off without providing a new one for the local club. As a result club managers know that they can risk financial failure without risking the life of the club itself. This is a version of the ‘too big to fail’ problem that affects the banking industry. (Storm and Nielsen described this in 2012). UEFA has introduced the system of ‘Financial Fair Play’ to try to limit the spending of clubs. However, it is not clear that these regulations will really benefit the fans. Given that clubs never disappear it is not clear why loss making is a problem, and there is a danger that restricting spending will just cement the power of already dominant clubs. (Franck provided an economic rationale for FFP in 2013, whilst Peeters and Szymanski (2014) present the case against.)

Even in England where clubs have long operated as limited liability companies with shareholders, the owners seem more interested in the prestige of ownership than making money. This might change as Americans have started to buy up clubs in England.

The US professional league model

Some people look at the business model of sports leagues in the United States, where clubs have made agreed rules on issues such as salary caps, the draft system for recruiting players and wide-scale revenue sharing. US leagues are certainly profitable, and a significant contributor to this is the absence of a system of relegation, which means that the consequences of sporting failure are quite limited. However, many fans of weak teams complain that their teams will never get better because the owners have no incentive to compete, and many cities lack the opportunity to see play at the highest level since there is no feasible mechanism to enter the league. (Ross discussed this in more detail in 1989. Szymanski (2003) presents a full-scale comparisons of the American and European systems.)

The future: Profit maximisation versus winning prestige?

Owners of American teams are often characterised as profit-maximisers who view professional sport as a business for making money. In Europe (and most of the world) football clubs have generally been seen as win maximisers – spending as much as possible on the success of the team subject to breaking even. (In 1971 Sloane wrote an early paper on this topic that is still highly readable. Késenne developed the concept of win maximisation in 1996.) This may just be a reflection of the competitive nature of the European system, but it also reflects a different attitude to the purpose of clubs. Some clubs (notably Barcelona and Real Madrid in Spain and most of the clubs in the Bundesliga) are not businesses in the normal sense but membership associations which elect the management board. Even in England where clubs have long operated as limited liability companies with shareholders, the owners seem more interested in the prestige of ownership than making money. This might change as Americans have started to buy up clubs in England – notably the Glazer family at Manchester United have taken a lot of money out of the club.

In 2021, twelve of the biggest European clubs, led by Real Madrid and including six clubs from the English Premier League, proposed a European Super League which appeared to be modeled on the US closed league system (the founder clubs would not have to qualify each season but would be guaranteed entry regardless of sporting merit). Proposals of this kind have circulated in Europe for more than thirty years (see e.g. Hoehn and Szymanski (1999)). Widespread public protests and the threat of intervention by football governing bodies and national governments led to the plan being abandoned within two days. Nonetheless, the proposal was based on a clearly profitable financial plan, coming at a time when many clubs are under greater financial pressure than usual due to COVID-19. It is quite possible that plans of this type will resurface again in the future. However, it is also possible that regulatory agencies will take steps to prohibit such developments. While American culture and business practices have been widely accepted and adopted in Europe, the American model of sports seems beyond the pale for Europeans, at least for the moment.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews