1.2 The Burgess Shale

High in the Canadian Rockies is exposed a deposit of middle Cambrian age, about 530 Ma old, called the Burgess Shale. It contains the fossils of animals that lived on a muddy sea floor, and which were suddenly transported into deeper, oxygen-poor water by submarine landslides. Their catastrophic burial has given us an exceptional view of Cambrian life. Not only have animals with hard shelly parts been preserved but entirely soft-bodied forms are also preserved as thin films on the sediment surface.

Before going any further, click on 'View document' below and read pages 62-65 from Douglas Palmer's Atlas of the Prehistoric World.

View document [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)]

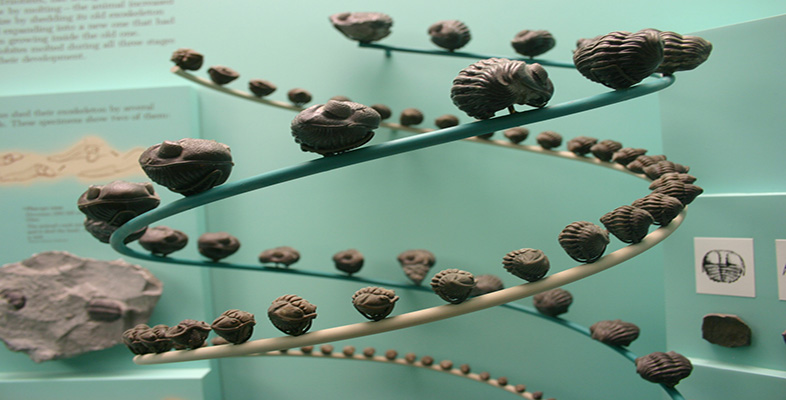

Some of the most common Cambrian fossils, which appear immediately after the first shelly fossils, are trilobites. These were a group of exclusively marine arthropods, members of the enormously diverse phylum of animals with jointed, external skeletons that today include forms such as crabs, lobsters, insects and spiders. The trilobite fossils of the Burgess Shale are like many trilobites found elsewhere but exceptional in that not only is the main part of their outer skeleton (or exoskeleton) preserved, but so too are their appendages such as antennae and legs (see, for example, those of Olenoides, Atlas, p. 63). Elsewhere, trilobite appendages are extremely rare as they were poorly mineralised. We will study trilobites in more detail shortly. Other types of arthropods, especially ones lacking well-mineralised exoskeletons (such as Marrella, Atlas, p. 64), are particularly abundant in the Burgess Shale.

Only about 15 per cent of the 120 genera present in the Burgess Shale are shelly organisms such as trilobites and brachiopods that dominate typical Cambrian fossil assemblages (fossils that occur together) elsewhere. The shelly component was therefore in a minority, and organisms with hard parts probably formed less than 5 per cent of individuals in the living community.

SAQ 4

If the soft-bodied fossils of the Burgess Shale are taken away, all that remains is a typical Cambrian assemblage of hard-bodied organisms. Why is this important to bear in mind when trying to interpret other Cambrian fossil assemblages?

Answer

The other Cambrian assemblages may also have been dominated by soft-bodied animals, even if the only fossils they now contain are of hard-bodied ones.

Another important revelation of the Burgess Shale lies in the wide diversity of animal types that were around in middle Cambrian time, about 530 Ma ago. There are representatives of about a dozen of the phyla that persist to the present day. One form closely related to early arthropods was Anomalocaris, the largest known Cambrian animal, some individuals of which may have reached two metres in length. Its extraordinary jaw (Atlas, p. 65) consisted of spiny plates encircling the mouth, which probably constricted down on prey in much the same way that the plates of an iris diaphragm cut down the light in a camera. This fearsome mouth is seen in place in the reconstruction of the closely related Laggania (Atlas, pp. 64-65). Note that the colours of organisms shown in this and other such reconstructions are conjectural.

About a dozen types of Burgess Shale fossils have been said to be so unlike anything living today and so different from each other that, had they been living now, each would have been placed in a separate phylum. With further study, however, the relationships of these puzzling animals (such as Hallucigenia, Atlas, p. 63) are becoming clearer. It seems that some Burgess Shale forms are hard to classify simply because the boundaries between major categories of animal life were still blurred shortly after the Cambrian explosion. In other words, by mid Cambrian time, there still had not been enough time for some groups to have diverged sufficiently from their recent common ancestors to be distinctly different.

Burgess Shale-type faunas have been found in about 30 sites ranging from North America and Greenland, to China and Australia. The wide range of animals they contain seems to reflect an unpruned 'bush of diversity' resulting from the Cambrian explosion. Not long after, though, extinction lopped off some of the branches, leaving phyla with the relatively distinct features that have remained to this day.