4.2 Crinoids

Figure 7 shows the fossilised remains of a type of echinoderm called a crinoid ('cry-noyed'). Although crinoids occur today, they were far more common in the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic Eras. Most crinoids feed by bending their umbrella-like arrangement of flexible appendages (called 'arms') downstream so as to catch a current, rather as in an umbrella being caught in the wind. Tube feet (multipurpose tentacles) on the arms gather food particles suspended in the water, which are then wafted by small hair-like threads in grooves along the arms to the central mouth. Most ancient crinoids lived gregariously in shallow, current-swept areas, free of muddy sediment that would otherwise have tended to kill them by clogging their feeding mechanism.

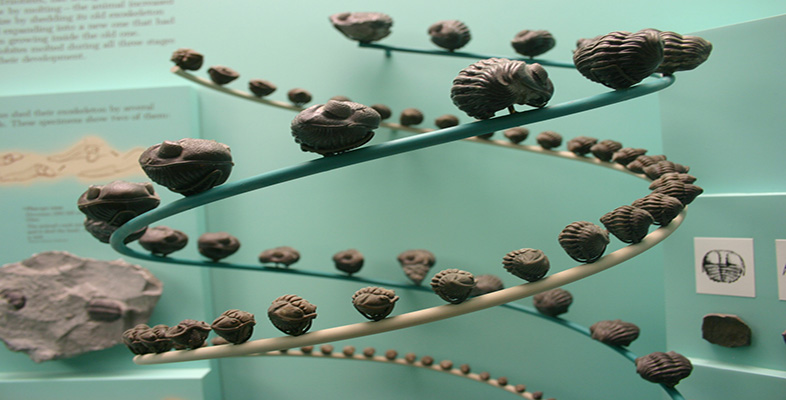

Most ancient crinoids were attached to the sea floor by a stem or stalk with a root-like holdfast. The mouth and gut were situated in an enclosed cup at the top of the stem. In life, the stem was fairly flexible, like the arms. The majority of living crinoids do not have a stem, and are capable of creeping around or even swimming. The few surviving stemmed forms generally live in deep water. Although they are animals, crinoids with stems look at first so like plants that they are often informally called 'sea lilies'. Shortly after death, the tiny organic fibres that alone hold the calcite plates together rot away, often causing the crinoid to disintegrate into separate plates that can be readily dispersed by currents or the movement of other organisms. In some ancient environments where crinoids were abundant, rocks have formed that are largely composed of isolated plates and stem fragments (Figure 8).

Crinoids have an arrangement of five 'rays', each of which carries one or more arms that together form an efficient food-gathering structure. Attached to each arm are many fine side-branches called pinnules, each made of tiny plates, which are also part of the food-gathering apparatus.