1.2.2 Reasoning by analogy

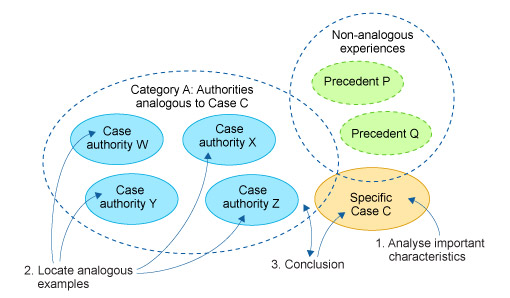

Reasoning by analogy involves drawing specific conclusions from other specific examples based on the similarities between them – the fact that they are ‘analogous’ to one another. When reasoning by analogy takes place, the objective is to say something specific about the case at hand based on the fact that it is ‘like’ other examples in certain ways. This can look a lot like how judicial reasoning takes place using case precedents. Consider Figure 4.

Here you are aware of the characteristics of your specific case (step 1), and you are aware of a number of previous cases that may share some of these characteristics with your case. You locate the examples that share the material characteristics of your case (step 2). These form a loose collection of analogous experiences (category A) which are similar to a general principle in inductive reasoning. In step 3, based on the similarities, you assume that your case has other similar characteristics to the analogous experiences, effectively placing your case within the same category as them. In judicial reasoning, this usually involves applying the same legal outcome to your case as was applied to the analogous precedent case or cases.

The conclusion using reasoning by analogy is much less likely to be certain than for deductive reasoning. It is sometimes considered a form of inductive reasoning, and is unstable because it relies heavily on the choices that you make about which pre-existing examples are similar to your case and why. The green exceptions in the diagram represent cases that you did not consider to be analogous to your case in important ways, so they are excluded. However, it might be that they share other similarities with your specific case that you did not think of, or did not consider important. In reality, therefore, your case may belong in a different category from that which you placed it on your conclusion. Or it may belong with both sets of examples at once, and you have had to make a choice about which cases are more similar in more important ways to yours to decide which legal outcome to transfer across. The truthfulness of the conclusion is entirely dependent on the strength and accuracy of the analogies drawn.