Any place on the Earth can be uniquely defined by its latitude and longitude, but in our everyday lives the names of towns, villages, streets and buildings provide a shorthand to help us identify a location. The origins of many ancient place names can often be traced back to a geographical feature, or the names and activities of the people who lived there, although many of the original meanings have been obscured by changes in language, pronunciation and spelling. But what about names for all the objects beyond the Earth?

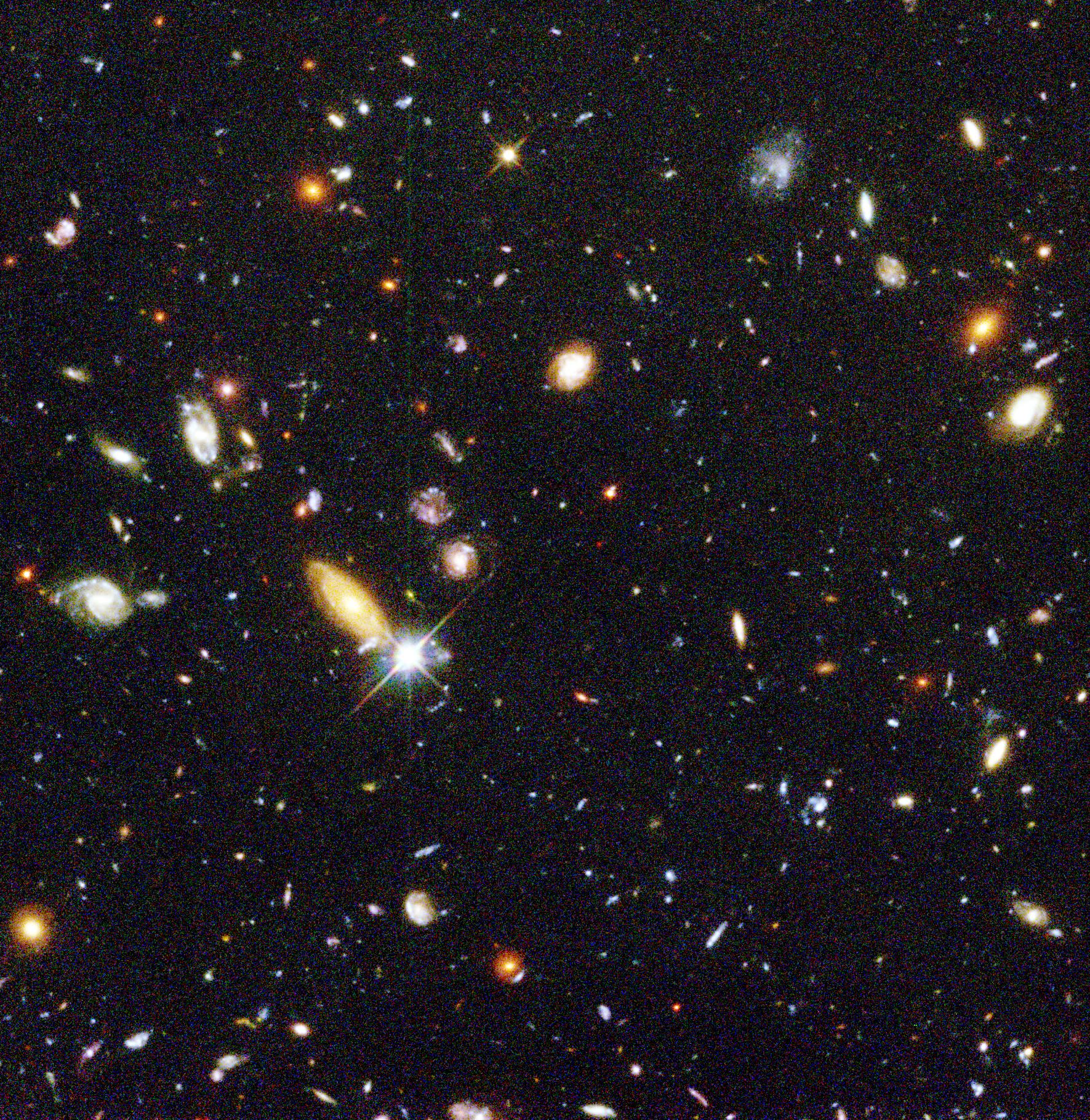

...It is not surprising that only the most prominent have names and most are identified by various catalogue numbers...There are around 5000 stars visible in the night sky; many of the brighter ones, together with recognisable patterns in their positions – the constellations – have been independently named in many ancient and more modern cultures across the globe, with numerous Greek, Roman and Arabic names in common use today. The Sun, a ball of gas emitting life-sustaining energy through internal nuclear reactions, is just one rather average star among more than a hundred billion stars in our Milky Way galaxy. In turn, it is just one of hundreds of billions of galaxies distributed throughout the observable Universe. With so many objects, it is not surprising that only the most prominent have names and most are identified by various catalogue numbers, usually including their positions in celestial coordinates.

While a friend or family member might appreciate the idea of being presented with their own star, in reality none of these names are official...Although, as for terrestrial places, people can use any name they choose, an official register of names avoids ambiguity or duplication. The names of astronomical objects are overseen by the International Astronomical Union (IAU), founded in 1919 to promote and safeguard the science of astronomy through international cooperation. Although the boundaries of the 88 constellations used today were formally defined in the 1920s, it was only in 2016 that the Working Group on Star Names (WGSN) was established to collate historical records and maintain the official catalogue of proper names for stars of scientific and historical value.

A casual internet search will reveal a plethora of companies who will readily sell you the right to name a star. While a friend or family member might appreciate the idea of being presented with their own star, in reality none of these names are official or legally binding in any way, and you may even discover that ‘your’ star has been sold several times over by different companies!

The currently known members of our solar system number 8 planets and 5 dwarf planets with over 200 moons orbiting them, nearly 4000 comets and more than a million asteroids, detected by the sunlight they reflect. For those visited by spacecraft we have identified surface features such as impact craters, mountain ranges, volcanoes, cliffs, valleys, and even hydrocarbon lakes.

Asteroids are generally named by their discoverers. Classical names are favoured for certain classes or potentially significant objects, but more or less any name can be proposed so long as it satisfies a few simple rules.The already established convention for the naming of planets after ancient deities was officially adopted by the IAU. English astronomer Sir William Herschel, the discoverer of the seventh plant in 1781, had suggested “Georgium Sidus”, or George’s Star, after his patron, King George III, before Uranus was finally adopted. The ninth planet, discovered in 1930 (now classified as a dwarf planet), was named Pluto for the Roman god of the underworld, following the suggestion of English schoolgirl Venetia Burney, to reflect its dark, cold existence at the outer edge of the solar system. Many features on Pluto are named for characters associated with the underworld. Different thematic rules apply to features on other planets and moons. Some might be anticipated, such as on Io, the volcanic moon of Jupiter, which includes myths and literary associations with volcanoes, fire, thunder, blacksmiths etc. Others are more unexpected, with sources as diverse as the works of Shakespeare and Tolkien, Celtic stone circles, coalfields, dogs, birds and dragons all featuring on different bodies.

Comets are the only celestial bodies that are generally named after their discoverer(s), although a few historical objects, including comet 1P/Halley are named after those who first determined their orbits. Up to three names can be assigned (either individuals or team names). The record for discoveries is held by SOHO (Solar and Heliospheric Observatory) with over a thousand.

Asteroids are generally named by their discoverers. Classical names are favoured for certain classes or potentially significant objects, but more or less any name can be proposed so long as it satisfies a few simple rules. Many are named after famous – and not so famous – scientists, including at least 15 past or present OU staff. You can find many celebrities and other unusual names such as 9007 James Bond, 13681 Monty Python, 17627 Humptydumpty, 2309 Mr. Spock (the discoverer’s cat rather than the Star Trek character) and 9000 Hal.

Animated image of Asteroid 69423 Openuni, made by OU research student Sam Jackson using images from the OU's robotic telescope, PIRATE, part of the OpenScience observatories.

Animated image of Asteroid 69423 Openuni, made by OU research student Sam Jackson using images from the OU's robotic telescope, PIRATE, part of the OpenScience observatories.

Asteroid 69423 Openuni celebrates the 50th anniversary of the OU’s creation on 23 April 1969 and its involvement in solar system exploration.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews