Valentine’s Day is built on familiar symbols: the red heart, the steady beat of a pulse, and the idea of ‘chemistry.’ Interestingly, we can find these exact same patterns in deep space. However, they aren't caused by biology or emotion. They are the result of fundamental physical laws. Gravity sculpts clouds into familiar shapes, quantum mechanics creates colourful light, and the conservation of energy keeps stars spinning at a precise rhythm.

Here is the science behind three cosmic phenomena that just happen to look, and sound, like the symbols of love.

1. Why does the universe glow red?

The Heart Nebula.

The Heart Nebula.

If you look at the constellation Cassiopeia, about 6,000 light-years away, there is a colossal cloud of gas called the Heart Nebula. It looks exactly like a Valentine’s symbol, and it glows a deep, rich red.

In movies, red is the colour of passion. In astrophysics, it is the colour of recombination.

The science behind this glow echoes the ultimate story of relationships:

- The Breakup (Ionization): At the centre of the heart, massive stars blast out intense Ultraviolet (UV) energy. This energy is so violent it tears atoms apart, stripping electrons away from their partners (protons).

- The Reunion (Recombination): The electrons don't stay separated forever. Eventually, they lose that excess energy and fall back into an orbit around a proton.

- The Glow: The moment they ‘reconnect,’ they release one or more particles of light. For hydrogen, this light is mostly a specific shade of deep red.

So, the beautiful red glow isn't just a filter. It is the visible sign of billions of atomic reunions happening every second. It reminds us that the brightest light often comes from the act of coming back together.

The heart shape itself is also a product of intense forces. The powerful winds from those central stars push the gas outward, sculpting a giant cave.

As the gas gets squeezed tightly at the rim of the heart, it collapses under gravity to form brand new stars. The ‘pressure’ of the environment isn't destroying the cloud; it is driving the creation of the next generation of solar systems.

2. Can a dead star have a heartbeat?

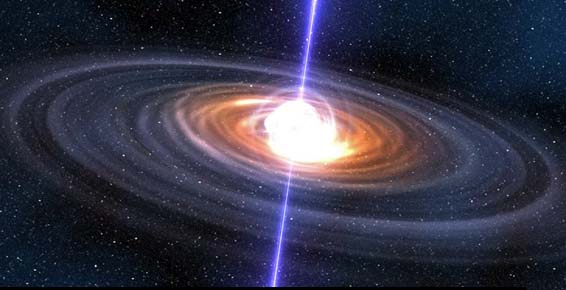

Artist impression of a Pulsar.

Artist impression of a Pulsar.

While the Heart Nebula gives us the image of love, Pulsars give us the rhythm.

In 1967, a PhD student named Jocelyn Bell (who later became an Open University Professor) noticed a ‘bit of scruff’ on her radio telescope charts. It was a signal from deep space that pulsed every 1.3 seconds (Hewish et al., 1968).

She had discovered a Neutron Star. This is the crushed core of a massive star that ran out of fuel. Imagine a star heavier than our Sun squeezed into a ball the size of a city (about 20km wide). Because it is so small, it spins incredibly fast—much like an ice skater pulling in their arms to spin faster.

As it spins, it sweeps a beam of energy across Earth like a lighthouse. We see this as a steady pulse. Some pulsars spin hundreds of times a second, but others, like PSR B0329+54, spin about 84 times a minute (Konacki et al., 1999).

If you listen to the data from that star, it doesn't sound like a whirring ball of gas. It sounds just like a steady human heartbeat. It is the ‘resting heart rate’ of the galaxy, and because these stars are the most accurate clocks in the universe, this heart will keep beating for millions of years.

3. Can a frozen world renew itself?

Pluto has a distinct heart shape on its surface known as the Tombaugh Regio region.

Pluto has a distinct heart shape on its surface known as the Tombaugh Regio region.

Finally, let's look at the edge of our own solar neighbourhood. When the New Horizons probe flew past Pluto in 2015, it sent back an image of a distinct heart shape on the surface of the dwarf planet.

Scientists call this region Tombaugh Regio. The leftmost lobe, known as Sputnik Planitia, is a vast basin filled with nitrogen ice, sitting at a freezing -230°C (Morison, Labrosse & Choblet, 2021). You might assume a world that cold would be static and frozen in time, but it is actually undergoing a constant state of renewal.

The nitrogen ice operates much like a giant lava lamp:

- Deep underground, Pluto’s core is slightly warmed by radioactive decay processes and residual heat from its formation.

- This warmth heats the bottom of the nitrogen ice layer, causing it to rise to the surface.

- The ice cools down upon reaching the surface and sinks back down again.

This constant churning process, called convection, means the surface is slowly recycling itself about once every 500,000 years. This movement wipes away impact craters and keeps the terrain distinctively young. It proves that even in the coldest, darkest reaches of space, there is a capacity to wipe the slate clean and begin again.

Final thoughts

Whether it is atoms finding each other again, a star that refuses to stop spinning, or a frozen world keeping itself warm, the universe is full of connection. The forces we associate with love: attraction, resilience, and rhythm, echoed throughout the universe.

See more of our Valentine's content in our OpenLearn Valentine's collection.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews