2.1 What is mind?

So the question was, and is, where does mind come from? What is it? To early civilisations, without complex technologies, mind and agency were ultimately mysterious, to be explained only in terms of spirits and the work of gods. In the legend of Talos, the mighty bronze warrior had a single vein passing from his neck to his ankle, closed off by one bronze nail in the ankle, through which flowed a divine, animating substance called ichor. The Golem was merely clay: it only achieved agency through the spirit breathed into it by the rabbi.

Even Descartes could not bring himself to accept that mind could have a mechanical origin. Although he saw both animal and human bodies as machines, he distinguished between animal behaviour, which is simply mechanical, and intelligent behaviour which he believed only humans are capable of:

It is also a very remarkable fact that although many animals show more skill than we do in some of their actions, yet the same animals show none at all in many others; so what they do better does not prove they have any intelligence ... It proves rather that they have no intelligence at all, and it is nature which acts in them according to the disposition of their organs. In the same way a clock, consisting only of wheels and springs, can count the hours and measure time more accurately than we can with all our wisdom.

After that, I described the rational soul ... that ... cannot be derived in any way from the potentiality of matter. And I showed ... it must be ...closely joined and united with the body in order to have ... feelings and appetites ... and so constitute a real man.

Descartes was what philosophers call a dualist. He believed that the mind and the body are completely different kinds of thing. For him, humans – and only humans – could be intelligent. Only humans had a rational soul, a non-material, immortal, thinking spirit inhabiting their bodies.

But others were prepared to go where Descartes could not, to think the unthinkable and entertain the idea that mind might also have a purely physical, mechanical origin. La Mettrie, who I mentioned earlier, ended his work Machine Man with a bold claim:

Let us, therefore, conclude boldly that man is a machine, and that the universe contains only one single, diversely modified substance.

This is in clear contrast to Descartes' dualism. La Mettrie was a monist and a materialist, holding that there is only one kind of substance in the universe – matter – and that thus, ultimately, both mind and body must spring from the same material causes. This philosophical debate between monism and dualism has persisted, in various forms, to the present day, without real resolution. We will have to leave it there.

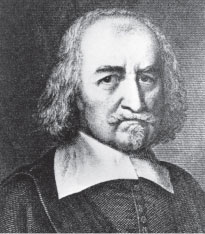

However, given the theme of our course, the key figure is the 17th-century thinker Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679). Like La Mettrie, Hobbes also believed that the mind was a material, mechanical thing, made of the same stuff as the body:

All ... qualities called sensible are in the object that causeth them [nothing] but so many several motions of the matter, by which it presseth our organs diversely. Neither in us that are pressed are they anything else but diverse motions (for motion produceth nothing but motion).

In other words, motions in the objects around us excite our senses and cause resonances in the particles that make up our minds. So, mind is just another material thing, like the body. But Hobbes went further: he claimed that the operations of the mind – what he called ratiocination, and which we can take to mean reasoning or thinking – was a form of computation. He wrote:

By ratiocination, I mean computation. Now to compute is either to collect the sum of many things that are added together, or to know what remains when one thing is taken out of another. Ratiocination, therefore, is the same with addition and subtraction.

So, thinking, for Hobbes, was just another form of arithmetic, but performed with concepts and ideas rather than with numbers. He goes on:

We must not think that computation, that is ratiocination, has a place only in numbers, as if man were distinguished from other living creatures ... by nothing but the faculty of numbering; for magnitude, body, motion, time ... action, conception, ... speech and names ... are capable of addition and subtraction. Now such things as we add or subtract, ... we are said to consider... to compute, reason or reckon.

Even more significantly, Hobbes wrote:

When man reasoneth, he does nothing else but conceive a sum total, from addition of parcels; or conceive a remainder, from subtraction of one sum from another: which, if it be done by words, is conceiving of the consequence of the names of all the parts, to the name of the whole....

Hobbes' sentences are difficult to unpick, but we need only focus on one word here: 'parcel'. If we substitute a modern word for this – symbol – we can try to summarise Hobbes' position simply and in more contemporary language.

Exercise 2

Try to sum up what Hobbes was trying to say about the nature of mind and thinking. He is a difficult writer, especially to modern readers, so you need only be quite general.

Comment

I thought perhaps the best way to sum it up is in a list:

- The world consists only of particles of matter in motion.

- Bodies and minds are also just particles of matter in motion. Their motions are caused, in part, by the effects of the movements of particles outside the body, which press on the senses, causing particles in our minds to move in sympathy.

- The particles in our minds form parcels: that is, symbols representing concepts such as number, time, names, and so on.

- Thought amounts to a form of computation, in which these mental symbols are added, subtracted, etc., in processes similar to those of arithmetic.

In short, for Hobbes, intelligent activity consists in a material body of some kind, using clear rules to manipulate internal physical symbols that stand for objects in the world. In principle, then, artificial minds could be built. And another serious question is raised by Hobbes' theory, too, although the philosopher might not have been aware of it. If thinking is essentially the manipulation of physical tokens that represent features of the world, then does it matter what those tokens actually are? They may be features of the brain in humans; but might they not equally be beads, tin cans or electric currents?

However, there is little evidence that any of the Enlightenment scientists seriously entertained the idea that an artificial mind might be built. As I suggested earlier, our view of ourselves as humans, and of artificial creatures that might resemble us, has always been conditioned by the technologies of our age. The science of the 17th and 18th centuries was not really up to the task of providing an adequate picture of how a thinking artefact might be constructed. This was to be left to a later era, with new technologies, which yielded new ways of thinking about the mind. But it was the philosophers of the Age of Reason who laid the intellectual foundations of one of the 20th century's great projects – artificial intelligence.