Find out more about The Open University's Science courses and qualifications

Manufacture:

- An alternative to expendable pattern investment casting (“lost wax process”), and shell moulding.

- Permanent patterns of metal, wood, resin, plaster or rubber eliminate several stages of the lost wax process, hence reducing costs. The patterns can be loose or mounted on pattern plates as in shell moulding.

- “Plaster process” uses flexible rubber patterns invested with plaster of Paris, which can be strengthened by the addition of fillers. Permeability of the mould can be increased by using porous fillers, foaming agents or steam autoclaving (the Antioch process).

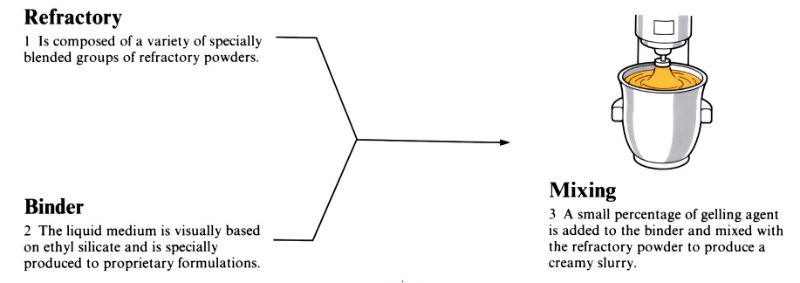

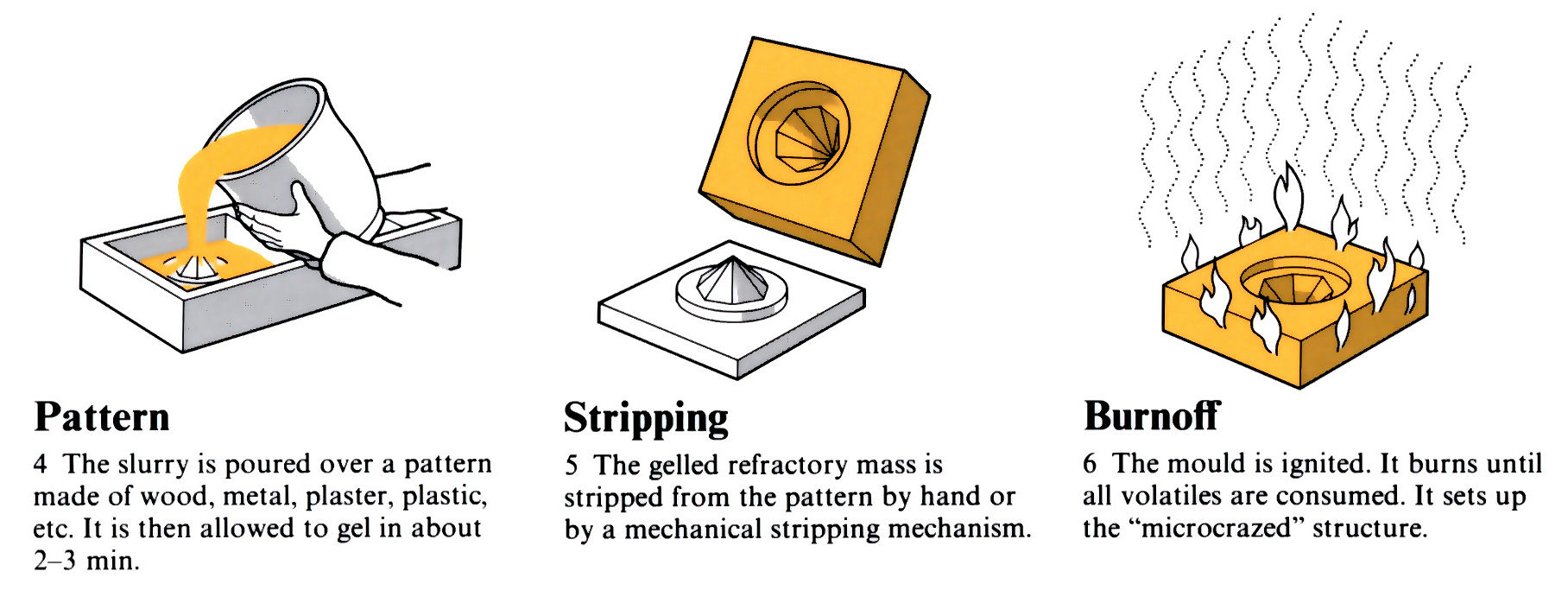

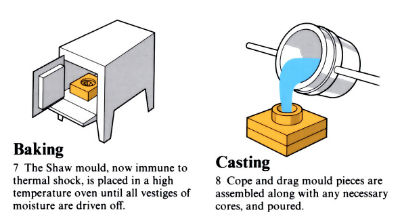

- “Shaw process” uses rigid patterns invested with high quality refractory mixed with ethyl silicate binder and gelling agent, which goes through a rubbery stage before setting, enabling the pattern to be removed. A cheaper back-up refractory is often used. Block moulds are most common, but shell moulds can be produced by pouring the investment between the pattern and a contour plate. The Shaw process is the only casting process where hot metal can be poured into cold ceramic moulds without cracking.

- Due to low pattern costs compared with the lost wax process, and cases where patterns can be altered, makes the process suitable for short production runs.

- Automated mould production and pattern stripping possible with simple shapes. More complex shapes require manual mould production and pattern stripping, increasing costs and reducing production rates.

- Typical components include steel and Cu/Be dies, and die inserts for forging, die casting, etc. (Shaw process), aluminium alloy impellors, torque converters and valve parts (Plaster process).

Materials:

- Plaster sands are only suitable for low melting point materials such as Al and Cu based alloys, and gold and silver jewellery alloys.

- Insufficient drying of plastic moulds can lead to hydrogen pick-up in aluminium alloys, causing porosity.

- Refractory moulds (Shaw process) are suitable for almost all castable alloys (see lost wax process) but are usually used with high melting point alloys such as cast iron, carbon and alloy steels, and Cu/Be alloys.

- The Shaw process can produce castings without the usual casting defects found in other processes. Benefits include:

high resistance to hot tearing

casting free from gas holes

inclusion-free castings

process permits “natural feeding” of the casting.

Design:

- Shaw process; complex 3D components moulded in two or more parts. Plaster process; complex 3D components.

- Flexible nature of mould/pattern eliminates need for taper, and allows slight undercuts.

- Parting line slightly reduces accuracy (compared with lost wax process), and leaves a small flash that has to be fettled.

- Detail and surface finish similar to lost wax process, but lower linear tolerances due to the need for accurate alignment of separate mould parts and cores.

- Shaw process gives excellent tolerances.

- Plaster process is less accurate, due to the flexible nature of the pattern, but the highly insulating nature of the mould enables thin sections of 0.25 mm to be cast.

- Castings from a few grams to 1 tonne can be produced, although with the plaster process the size is limited due to the flexible nature of the pattern.

This article is a part of Manupedia, a collection of information about some of the processes used to convert materials into useful objects.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews