Find out more about The Open University's History and Social Sciences qualifications.

This article belongs to the Women and Workplace Struggles: Scotland 1900-2022 collection.

Background

Women have frequently faced struggles to enter the workplace in roles considered traditionally male. Women’s workplace roles were often those associated with caregiving, such as nursing or teaching. This is because certain jobs were labelled and allocated according to gender and viewed by society as either masculine or feminine. This article examines the way that education constrained women’s careers from the beginnings of their lives, limiting their life choices. It also explores the story of Ann Gibbons, one woman who challenged gender roles in the workplace, and carved out a successful career for herself in the midst of a highly masculine work environment.

The Gender Context

Gender is a social construct which relates to ideas of what is feminine or masculine in a given society at a particular time. This means that it is a concept formed by human beings, and reinforced by social practices, which includes the belief that some roles and behaviours are more appropriate and suited to certain genders. People are socialised into gender roles within their societies from a very young age. For example, in Western societies, girls were traditionally given dolls and prams to play with, which would strengthen the idea that they would be feminine, nurturing caregivers as adults. In contrast, boys were encouraged to play more actively, with toy weapons and footballs, to support an adult, masculine role as protector of the family and provider. This underpinning of gender stereotyping continued into the education system, where girls were taught different subjects from boys, and reading books mostly featured male protagonists with women usually shown in domestic roles (Haralambos and Holborn, 1991, p. 284).

These roles were accepted as correct and reinforced by society. They were restrictive for all genders and very difficult to challenge, as to go against the norm could bring ridicule, social exclusion or even punishment.

Gendered Education in Scotland’s Schools

In 1965, Scottish education moved from a system of junior and senior secondary schools to a new structure of comprehensive schools. The previous system had allocated pupils to either the senior or junior secondary school on the basis of passing an intelligence-based qualifying exam, known colloquially as the ‘quali’. The ‘quali’ classified children’s intelligence at age 11, as something fixed and entire educational futures were decided on the results of just one exam. With the introduction of comprehensive education, this was abolished and now every pupil had access to a post-primary education. This meant that education could be more inclusive, as children were no longer segregated by an unfair exam. A new, more liberal curriculum was also introduced to give pupils a broader education which was accessible to all (Paterson, 2020). It was believed that the education system in Scotland could be designed to help tackle social inequalities, of which gender discrimination was one (Howieson et al., 2017).

In practice, although all pupils were introduced to subjects such as English, mathematics and science in their first two years of secondary education, the curriculum remained highly gendered for most pupils. Girls were expected to learn the domestic skills of cooking, sewing and housekeeping. Alternatively, they could choose ‘commercial’ subjects such as typing and accounting, as these were the types of jobs most women could expect to obtain after leaving school. However, the main emphasis of girls’ education continued to be on preparing them for future lives as wives and mothers and jobs which typically reflected these kinds of roles, for example, cleaning, catering, clerical, cashiering/retail and childcare. These jobs were classified as low-skilled, were underpaid and definitely undervalued (Close The Gap, 2012).

Challenging Workplace Gender Roles

Ann Gibbons is a good friend of the family, whom I have been privileged to know since I was a child. My family moved to a new area of Glenrothes in 1977, and my mum and Ann became firm friends. I had always known Ann as a hard worker, sometimes working three jobs to make ends meet, and as an utterly devoted mum to her two children. However, I did not really understand how challenging it had been for Ann to forge her career while a single mother. As we chatted, I soon began to realise and admire her determined character and sheer bravery, which pushed her throughout her life.

Photo - Ann Gibbons at school, aged 14

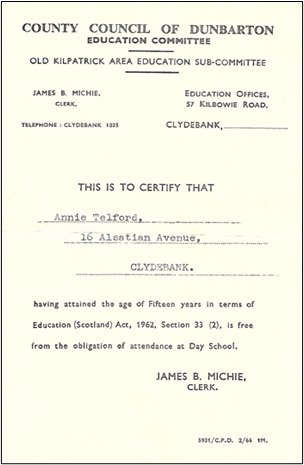

Ann Gibbons lives in Glenrothes in Fife and she is one woman who challenged gendered workplace roles. As a teenager, she attended Braidfield Secondary School in Clydebank, leaving school in 1965. At that time, girls were not allowed to take classes in technical drawing, woodwork, or metalwork, as these were deemed to be boys’ subjects, so Ann was led down the route of learning domestic and commercial skills. When thinking about her working future, Ann’s Careers Adviser told her what they told all the lassies – that she should go and get a job in a shop. Ann received her Leavers’ Certificate, given to each child at age 15, and was expected to follow this route.

Image – Ann Gibbons' (neé Telford) School Leaver Certificate

However, Ann had other ideas. Because she came from a family of engineers, her father encouraged her to try something different and, with his help, she gained a three-year position as an Apprentice Draughtsman’s Tracer at D. and G. Tullis, in Clydebank. The very title of the job betrays the gendered and hierarchical nature of the role at the time. The company was involved in light engineering, designing laundry machines for hospitals and prisons. Ann’s job was to trace the engineers’ drawings onto linen, in order to have a more robust copy. For the first year of her apprenticeship, she learned how to print the alphabet by hand. This was done using ink from inkwells and was a messy business, for which she had to wear long-sleeved overalls. This took a lot of patience and dedication, but she soon excelled in this skill. On her own initiative, she also attended night classes at Clydebank Technical College to learn technical drawing, an opportunity she had been denied at school because she was female.

Tracing plans onto linen was a precise and highly skilled job, where no mistakes could be made, as materials were not to be wasted. Too much ink in the pen would mean a blot on the linen and the drawing would be spoiled. They worked from boards which could be tilted and used tools such as set squares, straight edges and curves (Blog at The Ballast, 2021). Therefore, this was an important position within the workforce. However, this was a traditionally male working environment. It was not uncommon for men to put an uninvited arm around a female co-worker when inspecting their drawings or giving instructions. Ann recalled that whenever she went into the drawing office, where the engineers worked, she repeatedly had her bottom pinched by one of the men. This happened so often, and made her feel so angry, that eventually she slapped the man to let him know that this was not acceptable. She spoke with her boss about this and the man in question was told not to do this again.

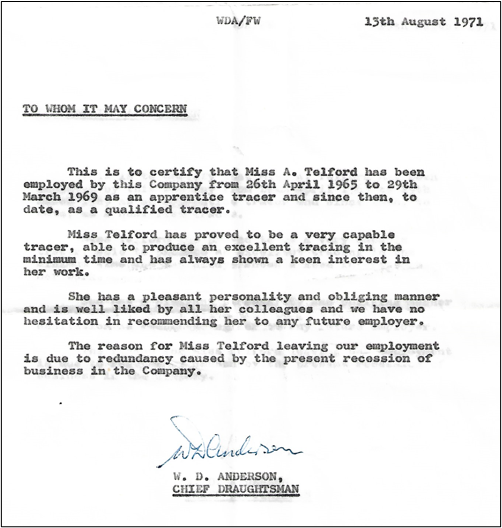

Sadly, because of recession in the business, Ann was made redundant at the end of her apprenticeship. However, her glowing reference made her eager to pursue more work in the field.

Image - the redundancy letter Ann received in 1971

Married Women Will Not Be Employed!

Ann then interviewed with British Telecom, in 1971, to work for them on plans and cables in a five-year apprenticeship. However, one of the conditions of employment was that she must not get married. Outrageously, men were not held to this condition. Therefore, she was expected to remain single for the five years of her apprenticeship. At the time, Ann was engaged to be married and so she could not accept the position, despite her evident suitability for the role.

At this time, many employers argued that they would not waste training and resources on a woman, who would obviously then leave to marry and have children. Although many years before, the introduction of the Married Women (Employment) Act (1927) prevented the ‘…refusal to employ women in the public service by reason only of their being married.’ (nationalarchives.gov.uk, n/d), this only related to employment in government, local and public office: therefore, private employers could choose to ignore this.

Oh Yes They Will!

However, in 1975, the Sex Discrimination Act came into force, along with the implementation of the Equal Pay Act of 1970. The Sex Discrimination Act meant that discriminating against women in employment, training and education was illegal, and this included refusing to employ married women (Court, 1995). Around this time in the UK, the percentage of women in couples without children who worked was around 68%, while the figure for women in couples with children who worked was 48% (Roantree and Vira, n/d). The overall percentage of UK women working in 1975 was 55.6% (ONS, 2021). Therefore, there was still a substantial minority of women who did not work outside the home.

Pushing the Role Further

In 1975, Ann moved to Fife and a year later began working outside the home at Westfield Gasification Centre. She created drawing plans for the gasifiers, which were machines used to make synthetic natural gas from coals imported from the USA.

Later, in 1983, Ann moved to Fife Council and once again was employed as a Tracer, working in Glenrothes at Rothesay House. Here, she continued her career having had her children. She worked alongside Chartered Engineers and Technicians on road design. At this time, new technology such as the MOSS and AutoCAD software was being introduced, although hand drawing of plans continued. The new software allowed technicians to create 2D and 3D drawings with the help of computer-aided design tools.

Photo - Ann Gibbons drawing up plans using a mechanical T-Square, at Fife Council, circa 1988

Ann and another female colleague asked to be trained on the new software, as they were keen to develop their skills. Their request was met with a definite ‘No’ and they were informed that this was only for the Engineers and Technicians, who were all male. They felt this was very thinly disguised sex discrimination, which flew in the face of the 1975 Act. Therefore, Ann and her colleague persisted and eventually an Engineer trained them on the technology. She soon became extremely confident with this, although she felt it lacked the creativity of drawing by hand. Ann’s skills in technical drawing were therefore further enhanced, but only by dint of her own perseverance and by pushing against workplace discrimination. Ann worked for Fife Council for 28 years and retired in 2011. Her determination to succeed while challenging workplace gender roles took courage and grit and paved the way for women who came after.

Photo - Ann in 2021

More Women Needed in Technology!

Equate Scotland is an organisation dedicated to helping more women into science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). They estimate that currently only 25% of those working in the STEM sector are women and argue that a more diverse workforce is needed for ‘profitability, productivity and creativity across industry’ (EquateScotland, 2021). Although STEM subjects are studied by all genders, a separation occurs around the teenage years and from then on it is still boys who are more likely to study subjects such as engineering and computing. Therefore, education continues to be split along gender lines, which means that for women, breaking into these fields of work remains challenging.

However, there is some good news. In 2018, figures from Skills Development Scotland reported that the number of women in tech jobs had risen from 18% to 23.4% and more than doubled since 2010, from 10,300 to 24,000 (Skills Development Scotland, 2018). In 2019, on International Women’s Day, Unite union and the West College Scotland Clydebank held an open day which saw women try MIG (metal insert gas) welding, to encourage women into this male-dominated industry (West College Scotland, 2019). Trades unions regularly campaign on the gender pay gap, as figures show that, on average, men earn 18% more than women (ONS, 2017, cited in Unison, 2022). In addition, organisations such as Girl Geek Scotland, Equate Scotland, Education Scotland, and the Scottish Government are working together to promote STEM subjects to girls and widen interest.

Concluding Comments

Women have made great strides into traditionally male careers and are challenging these all the time. Ann Gibbons’ story demonstrates that women have always had the talent and strength to work in the same careers as men, but had to break down barriers at every turn to gain entry. Ann’s determination to create a career by chipping away at these obstacles shows great inner resolve and purpose.

With continued collective effort and perseverance, the idea of a gendered work role will become a thing of the past.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews