Governments are at a critical juncture in how they respond to the issue of homelessness and evictions. The policy initiatives rolled out in response to the Covid-19 pandemic provide local and central government with an opportunity to rethink the statutory safety net for people who are homeless and those at risk of becoming homeless. The ramifications of the economic fallout of Covid-19 are slowly becoming apparent and it’s crucial that we avoid the same crippling austerity measures that led to the sharp increase in homelessness and an unprecedented wave of evictions between 2010 and this year. To prevent a repeat of that scenario, radical and meaningful policy initiatives must to be developed now, to secure the housing future for thousands of adults and children.

Traditionally, homeless people have been subject to social and political processes that seek to organise them into one of two demoralising categories: ‘deserving’ or ‘undeserving’. The statutory homeless assessment framework in the UK functions in ways that seek to divide homeless people into categories of ‘priority need’, and ‘intentionally’ or ‘unintentionally’ homeless. It’s a highly technical and bureaucratic approach that begins with an ‘eligibility’ test, to determine who is offered so-called ‘full duty’ housing support, and who is not.

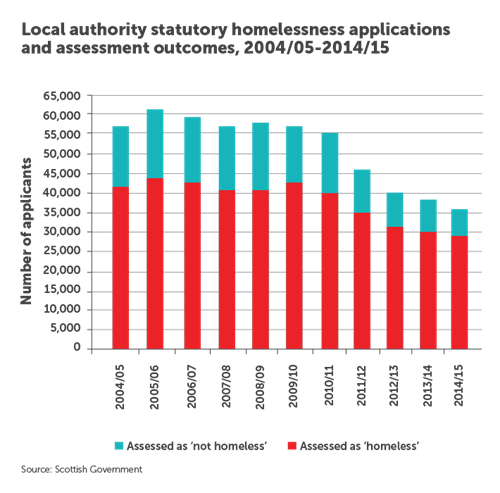

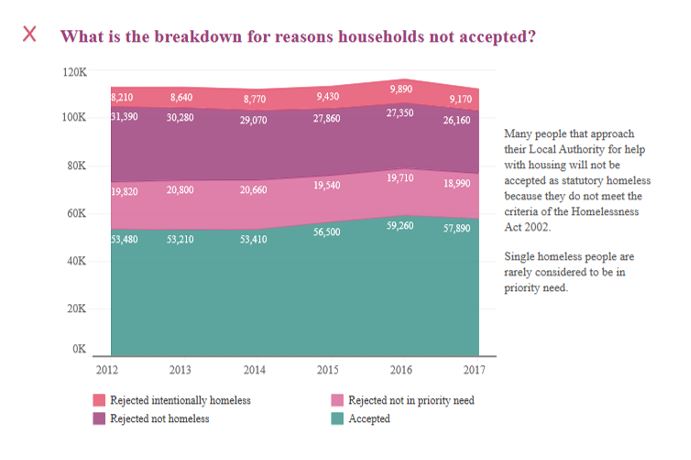

Applicants must prove that they have done everything in their power to prevent them from becoming homeless - to show that they are ‘unintentionally’ homeless. In order to be entitled to full duty housing support, they must further demonstrate that they are ‘vulnerable’ enough to be deemed a ‘priority’ – with Scotland being the exception, having abolished ‘priority need’ categories in 2012. In Scotland, where ‘priority need’ has been abolished, around 80% of all homelessness applications are offered support (see graph 1 below); whereas in England, only around 50% are offered full duty housing support (see graph 2 below). To put it simply, it is not easy for a homeless person to prove that they are entitled to full duty housing support from the state, especially when deservingness is the key instrument for determining eligibility.

Graph 1: Local authority statutory homelessness applications and assessment outcomes in Scotland, 2004/05 – 2014-15.

Graph 2: Breakdown of accepted and not accepted applications for homelessness support in England, 2012-2017.

Statistics don’t reveal the whole picture

While government statistics tell us something about the size and scale of the homeless problem, they are partial and do not reveal the whole picture. Not everyone who is homeless makes an application to their local authority. This group of homeless people are broadly defined as ‘hidden homeless’. There is no agreed definition of hidden homelessness, but the term is often used to describe people living in precarious accommodation, whose housing struggle is invisible to official state authorities and national data. Experiences of hidden homelessness can include, for example, people living on friends’ couches (‘sofa surfers’), squatting, living in derelict buildings, as well as rough sleeping.

The Everyone In initiative led to some 15,000 rough sleepers being accommodated in hotels (organised at local level). Rough sleepers didn’t need to divulge their personal and traumatic histories to prove their deservedness.

Being homeless in any form can be a traumatic experience and may lead to other injustices and harms. The stigma attached with being homeless is profound and can be experienced on many deep-seated levels, affecting people in both psychological and physical ways. Stigma describes the feeling of shame of humiliation and of being excluded from mainstream society. However, stigma is not simply a naturally occurring phenomenon; it is constructed and engineered at a much wider political level. The sociologist, Imogen Tyler, argues that stigma is crafted as a strategy of government, where ‘stigma power’ is exercised in multiple ways to exclude and control targeted populations. Drawing on those ideas, it can be argued that the statutory safety net is a stigmatising process that seeks to blame deserving and undeserving applicants for a failed housing system.

Then came the pandemic

Governments were quick to realise that the statutory assessment framework was too cumbersome and not inclusive enough to adequately respond to the homeless problem at the height of the pandemic. Consequently, this framework was suspended and the Everyone In initiative came into force. The Everyone In initiative led to some 15,000 rough sleepers being accommodated in hotels (organised at local level). Rough sleepers didn’t need to divulge their personal and traumatic histories to prove their deservedness and, moreover, the arbitrary power of local authorities for determining eligibility, was suspended. This inclusive approach was extended to include housed people, with the government instituting a temporary delay on evictions from mortgaged and rented properties. ‘Unprecedented’ some would say, but these measures are only temporary.

Imperfect, but better

The key message to take from this time is clear: we need a radically different approach to solving the homelessness problem, and this pandemic shows that one is possible. For years, politicians have claimed that there is not enough housing to accommodate everyone, hence the proclaimed need for an assessment framework that limits housing provision to people who are in ‘priority need’ and are ‘unintentionally’ homeless (those deemed in policy terms to be ‘deserving’).

For years, we’ve been told that a significant proportion of people sleeping rough are too chaotic and complex to house. Governments have been too complacent for too long, satisfied with the stringent provision of accommodation to rough sleepers only when temperatures fall below zero, for three consecutive days! The inclusive policy approach rolled out under Covid-19 shows that legislative intervention can prevent thousands of households from free falling into homelessness and can save lives – so why stop now?

View our dedicated hub on homelessness

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews