2.2 So, what is the state?

The kind of everyday practices and representations of the state in Jill’s story shape, for the anthropologists Aradhana Sharma and Akhil Gupta (2006), the ways in which people experience and learn about the state. But what is the state, exactly, and where is it? From Jill’s story, it seems that the state is everywhere, enmeshed in our daily lives through a complex assemblage of institutions, practices, people and discourses.

- It is worth saying that we could have given more examples of state presence drawing on Jill’s story; you might want to have a go at listing more examples yourself.

So, there are many and varied practices through which the state orders – or attempts to order – our lives. Or, to put it another way, there is a lot of political ordering going on in ordinary, everyday life. This fact tells us something about what the state is – it is the thing that does all this complex ordering. But the state remains a rather elusive thing. One might say that it lacks ‘thingness’. For example, I can visit a government department, see my NHS doctor, phone the police, write an email to my local council representative and correspond with the tax office. But the state is always more than each of these things – perhaps it is not so much a thing as a rather abstract idea which, in a sense, ‘sits behind’ all of these organisations. The state as such does not appear – it seems to be everywhere and nowhere at the same time. This is one reason why the emphasis on practices is important. But there is a sense in which the state is less abstract, or more concrete. We could say that the state is all the organisations and agents through which and by which these practices are made and remade. So, in that sense, the state is also a set of organisations.

Taking the state as a set of organisations, we can see that the state today is a much larger, more complex, and more numerous set of organisations and practices than it was two hundred, one hundred or even fifty years ago. The English historian A.J.P. Taylor argued that, until August 1914, the state left the adult citizen alone and ‘a sensible, law-abiding Englishman could pass through life and hardly notice the existence of the state, beyond the post office and the policeman’ (1975, p. 25) (Taylor was writing specifically about England, but what he says applies more generally across the UK). This is certainly no longer the case today. For Taylor, it was the First World War, and then the Second World War, that increased the reach of the state into the daily lives of both men and women, as all aspects of the economy and society were drawn into the war effort on an unprecedented scale:

The mass of the people became, for the first time, active citizens. Their lives were shaped by orders from above; they were required to serve the state instead of pursuing exclusively their own affairs. Five million men entered the armed forces, many of them (though a minority) under compulsion. The Englishman’s food was limited, and its quality changed, by government order. His freedom of movement was restricted; his conditions of work prescribed. Some industries were reduced or closed, others artificially fostered. The publication of news was fettered. Street lights were dimmed. The sacred freedom of drinking was tampered with: licensed hours were cut down, and the beer watered by order. The very time on the clocks was changed. From 1916 onwards, every Englishman got up an hour earlier in summer than he would otherwise have done, thanks to an act of parliament. The state established a hold over its citizens which, though relaxed in peacetime, was never to be removed and which the Second World War was again to increase.

States today do more, and they need more people and more organisations (departments, agencies, advisory and regulatory bodies) to do so. States are now so large and complex in terms of both their structures and their functions that Christopher Hood (1982), a political scientist, has argued that the bodies that now make up the state are ‘a formless mass’. One hundred years ago, even basic ideas of the welfare state, with its structures and operations around health, education and social services, barely existed. Today, along with defence, these are the largest areas of state policy and provision, even after privatisations (the transfer of state bodies and functions to the private sector) and the rise of the market principle from the mid 1980s across Western and a number of other democracies. The economic and social role of the state increased again as a consequence of the financial crisis and downturn beginning in 2008. The large array of things that the state now does requires not only more state employees and agencies, but also more complex patterns of interaction and interdependence between different state bodies, as well as between state bodies and non-state bodies. In short, contemporary states not only consist of enormous numbers of agencies, but they perform an enormous variety of functions.

The size of the state, its organisational complexity and its variety of functions all combine to make the state a difficult thing to grasp (we noted above how it seems to have this ‘abstract’ quality). Have you ever tried to grasp ‘a formless mass’? But there is another reason why the state is difficult to define. In some ways, it appears to be something more than its personnel, its institutions, its practices and its discourses. What is this ‘more’ that we are talking about here? To try to understand this we will use The Open University as an example. To start with, The Open University consists of all the people who work there in various capacities and of all the people who study with the University. It is also made up of material things, such as its buildings, its computers and all of the course materials generated there, and it is made up of countless practices and daily activities, such as carrying out research, producing courses and marking exam papers. The Open University also presents itself to its employees, its students and the wider society through its official brand, which appears on internal and external communications, and through its advertising in various media. But The Open University also gives the impression that it is more than the sum of all these parts. It appears to have an existence independent of the people, institutions and practices that compose it, akin perhaps to the fictional Unseen University in Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novels. The Unseen University, which some believe is inspired by The Open University, has an official motto ‘Nunc Id Vides, Nunc Ne Vides’, loosely translated as ‘Now you see it, now you don’t’.

We can see this same effect when we try to pinpoint what it is we are talking about when it comes to the state. It is reflected in the distinction that some political scientists make between governments and the state. Government is generally understood as the group of ministers (about 100 people in the UK, led by the Prime Minister) who are collectively responsible to Parliament for making and implementing policy on national issues. While particular governments come and go, mostly as a result of victories and defeats in national elections, the state is ‘a continuing, even permanent, entity’ (Heywood, 1994, p. 38). More accurately, there is a continuous attempt to create an impression that the state is a permanent thing, even if, in reality, some states also come and go (think of Yugoslavia, for example, a state that no longer exists, having been broken up in recent years into a number of new states – Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Slovenia, Montenegro, FYR Macedonia and Kosovo). But, how is this quality of permanence and continuity created? Sharma and Gupta (2006) argue that the everyday bureaucratic practices and the representations of the state (of the kind encountered in Jill’s morning) contribute to building up an image of the state that is coherent, unified and dominant across time and space. As a result of the seemingly endless repetition of everyday practices and the images the state presents to us, perhaps (for example) through the uniforms state agents wear, the buildings they work in or discourses in the media, the state comes to assume a dominant and permanent position in our lives as something with a ring of solidity to it. This is reflected in Benjamin Franklin’s famous adage that ‘In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes’. This idea of permanence and solidity is what the political scientist Timothy Mitchell (1999) terms ‘the state effect’. For Mitchell (1999, p. 180), the mundane activities and state discourses that we talked about in Jill’s story all help to give the impression that the state is more than just the sum of its parts.

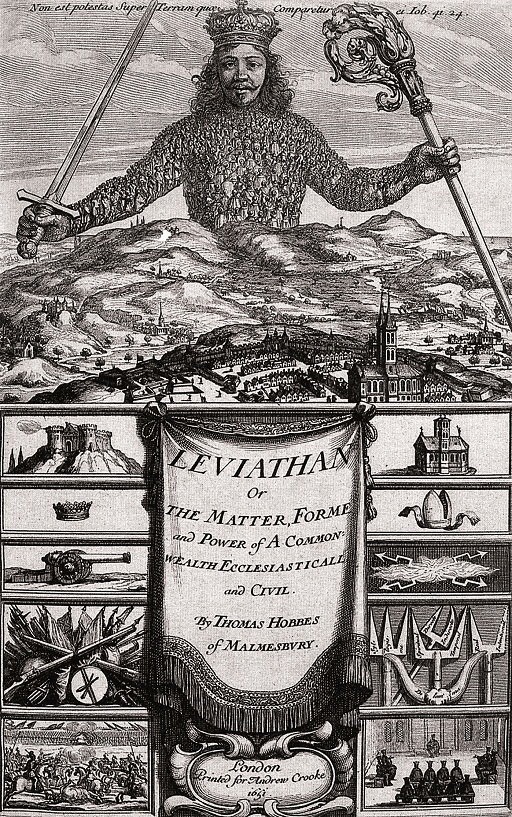

From the above, you might have the impression that the state is overpowering and all-pervasive. Certainly this is one image of the state that many have held, past and present. As Figure 2 shows, the frontispiece of one of the most famous books on the state, Leviathan, written by the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes in 1651, a time of widespread and dangerous religious strife, certainly appears at first glance to offer us this image.

Hobbes’s leviathan state, portrayed by the giant body of the king or ruler, towers over the people and territory it rules. And yet, on closer inspection, we can see that Hobbes’s leviathan state is composed of countless individuals. The state appears to dominate those individuals (and in Hobbes’s account, the state is certainly there to keep its citizens in awe), but the state also depends on those same citizens for its very existence. Today, we can see that the mundane, repetitive practices that build up an image of the state as coherent and unified depend precisely on the activity of citizens, whether or not they work for the state.

For example, the census illustrates one way in which individuals experience the state. Through the census, the state literally comes through a person’s front door in an official envelope, and individuals are asked to fill in the form following the categories the state has chosen to employ. And yet, a significant proportion of the British population chose to subvert the process by ignoring the classifications delineated by the state and identifying their religion as Jedi. Others may well have subverted the process by refusing to fill in the census or by filling it in incorrectly. Thus, there is ‘nothing straightforward or obvious about the production and reproduction of the state effect’ (Sharma and Gupta, 2006, pp. 17–18).

Summary

- Creating and maintaining political order is largely the job of the state, which we can define as a set of practices, a set of institutions and as a rather abstract idea.

- The state is visible in everyday life through a complex assemblage of institutions, practices, people and discourses which provide social order.

- Most states today are large and complex, and they require more people and more organisations to carry out their functions.

- The repetition of everyday practices and discourses creates the impression of states as permanent and continuous institutions.