Find out about The Open University's History and Social Sciences courses.

This article belongs to the Women and Workplace Struggles: Scotland 1900-2022 collection.

Setting the scene

On 12 August 2022, Scotland’s highest circulation broadsheet newspaper, The Herald, carried a headline exclaiming ‘Nurses set to strike for first time in their history’. While the words made an eye-catching headline, they failed to recognise, and in effect denied, the history of industrial action by nurses, mainly women, in Scotland over the last fifty years.

Strike action by nurses in Scotland has without doubt been very limited both in terms of the numbers participating and with respect to the length of action, but it has evidenced a desire and will to fight for better pay and working conditions as well as a more general defence of the National Health Service. It has also reflected a societal change toward equally valuing what has traditionally been viewed as ‘women’s work’, and at the same time brought nurses more and more into the collegiate world of trade unionism.

At the time of writing in October 2022, we wait to see whether such a direction of travel towards direct action will be reinvigorated or whether rhetoric will prove stronger than such action.

Reflecting on nurses disputes in Scotland

The first nurses’ strike in Scotland since the setting up of the NHS took place in the summer of 1974 and was very limited. The dam broke after years of nursing pay falling further and further behind other workers to the extent that ‘some ward sisters after deductions took home as little as 60 pence an hour’ (Lewis, 1976, p. 641) and ‘a typist with five years’ experience can get nearly £250 more than the staff nurse who is one of the key figures in any hospital ward’ (Hamilton, 1974).

The action was limited to nurse members of the Confederation of Health Service Employees (COHSE) and mainly occurred in psychiatric hospitals where the profession was more male dominated and was usually only of a few hours’ duration (Cohse-union.blogspot.com). The action was criticised by the National Union of Public Employees (NUPE) the other general union which had nurse members and was totally condemned by the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) which at that time represented most nurses and had a no-strike clause in its constitution. The RCN’s main contribution to the dispute was in effect a threat to privatise the NHS by stating if a satisfactory pay offer was not made it would call on its members to resign from their NHS jobs and for the RCN to then act as a nursing agency and hire its members back to the service (Lewis,1976, p.642).

In 1974 the newly elected Labour Government led by Harold Wilson settled the dispute with what were seen as ‘sizeable settlements although they were highly stratified and in effect gave comparatively little to the junior grades (Widgery,1976, p.301).

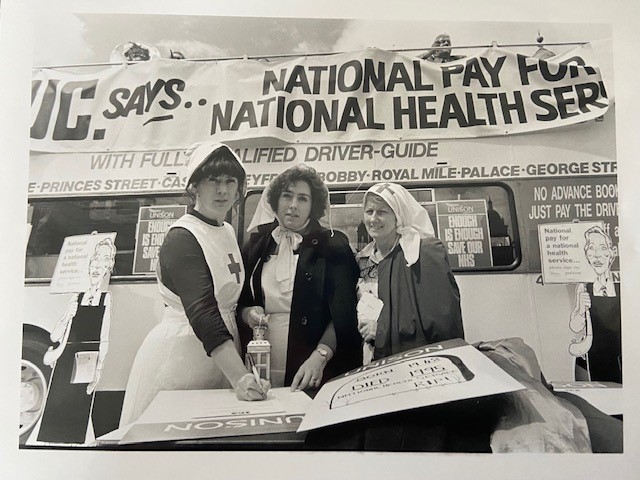

Unison Lothian Health BranchAfter those

first strikes of 1974 others followed in 1979 and 1982, but only a handful of

nurses were involved with action lasting a day or less and were very much of a

symbolic nature with it being left to ancillary staff to head up any NHS industrial action.

Unison Lothian Health BranchAfter those

first strikes of 1974 others followed in 1979 and 1982, but only a handful of

nurses were involved with action lasting a day or less and were very much of a

symbolic nature with it being left to ancillary staff to head up any NHS industrial action.

The first indication of nurses becoming more engaged in industrial action was in 1988, when there were three separate strikes over the course of the year involving nurses. The first was in January with a hundred nurses going on strike in Lothian and Lanarkshire over the UK Conservative Government of Margaret Thatcher instructing Scottish Health Boards, via the then Secretary of State for Scotland, Michael Forsyth, to put hospital domestic and catering services out to compulsory competitive tendering. While the vast majority of those taking action worked in the affected ancillary services, nurses acted not only in solidarity with their trade union colleagues but over concerns such processes would result in job losses meaning nurses would be expected to take on general cleaning duties in wards to cover the shortfall (Aberdeen Press and Journal,1988).

The second strike would follow weeks later with the Scottish Trade Union Congress organised ‘Day of Action’ in defence of the NHS with the emphasis again pretty much on the privatisation of ancillary services. The protest itself achieved a good deal of popular support with over 60,000 attending rallies and demonstrations across the country. The actual number of nurses taking strike action along with ancillary staff however probably didn’t total more than a couple of hundred, although a least some nurses were involved in strike action across most Scottish health board areas. The most significant action was again in Lothian with 80 nurses on strike (Lothian Courier,1988).

The hope behind the action was summed up by Lesley Garbutt, a staff nurse at Glasgow’s Southern General Hospital, who said, ‘I hope Mrs. Thatcher pays attention and listens to this protest’ (Daily Record, 1988). The reality was that Mrs Thatcher was not one for listening to the voice of trade unionists on strike. On this occasion Thatcher and Forsyth held almost all the winning cards. The Tories had just been returned for a third term in Government only eight months earlier and the privatization of NHS ancillary services had already been introduced in England. The largest nurses’ body, the Royal College of Nursing, still operated a no-strike policy and refused to countenance any industrial action strategy with the general unions NUPE and COHSE. If anything, the RCN double downed on its opposition with Ann Martin, the RCN’s senior officer in Scotland, telling members they would be expelled from the organisation if they went on strike. Finally, even where nurses did act it was for single days and minimum staffing levels were agreed for wards where nurses were on strike.

A common refrain of the time was that wards were so short staffed that emergency cover on strike days was larger than the staffing on a normal shift. At most the strikes were a minor inconvenience to both employers and patients and the outsourcing of ancillary services continued apace.

Nurses’ pay continued to be of major concern and by the end of 1988 it had hit crisis point, with 40% of all nurses earning less than the Low Pay Units threshold of £132.27. The starting salary of police constables and firemen equaled the maximum wage of a staff nurse or midwife at the top of the incremental scale. The image of nurses working as ‘angels’ continued with the common argument that low pay was justified as nurses were either ‘single women who will soon leave to get married, confirmed spinsters who do not need much money, or married women who are working for pin money’ (Delamothe,1988). Over and above the sexist nature of such arguments was research showing in one English Health Authority 11% of one parent families were headed up by nurses (Delamothe,1988).

Remembering the nurses strike of 1988

The third dispute of 1988 occurred in December and was solely a nurse’s dispute on the issue of pay after nurses were promised significant pay rises but once again found that the small print of the regrading exercise would mean that the headline figures would apply to a limited few. Disputes flared up across Scotland with the most significant being in Lanarkshire with around 60 nurses going on strike for 48 hours.

Nurses fighting to defend pensions

Scottish NHS nurses vote on strike action in 'unacceptable conditions.'Nearly a

quarter of a century passed until the next time (2011) when nurses were on the

picket line across Scotland and was once again part of a more general dispute

by NHS trade unions and workers, this time about pensions. After 13 years out

of power, in 2010 the Conservative Party were back in government, even if short

of a parliamentary majority; they were forced into a coalition with the Liberal

Democrats, although policy differences between the two parties may have been

invisible to the naked eye. In 2011, one year of being back in power, the UK

Coalition Government took a scythe to the NHS pension scheme ending among other

things the final salary scheme and raising the retirement age to put it in line

with the state pension age, also soon to be 67.

Scottish NHS nurses vote on strike action in 'unacceptable conditions.'Nearly a

quarter of a century passed until the next time (2011) when nurses were on the

picket line across Scotland and was once again part of a more general dispute

by NHS trade unions and workers, this time about pensions. After 13 years out

of power, in 2010 the Conservative Party were back in government, even if short

of a parliamentary majority; they were forced into a coalition with the Liberal

Democrats, although policy differences between the two parties may have been

invisible to the naked eye. In 2011, one year of being back in power, the UK

Coalition Government took a scythe to the NHS pension scheme ending among other

things the final salary scheme and raising the retirement age to put it in line

with the state pension age, also soon to be 67.

Although nurses took part in the dispute, and probably to a greater extent than they had before as they saw themselves forced to work longer and their long-term financial security put at risk, whether their specific action made an impact is highly questionable. The Royal College of Nursing once again refused to ballot its members, the general unions led by UNISON (following a merger of NUPE, COHSE And NALGO) in 1993 agreed minimum staffing levels which again meant little difference from nurses on duty from any other day, and once again the action was limited to one day. Concessions on levels of protection for those nearing retirement and on the figures by which future pensions would be calculated were won but there was no lasting impact on the headline changes.

So much for

the past, but what about the present, that is late 2022? As all the major trade

unions in the NHS move to ballot their members, what if anything will be the

difference if nurses go on strike in late 2022 and into 2023? The first

difference is the general mood. After two years of the COVID-19 pandemic in Scotland

health waiting times and waiting lists are through the roof at the same time as

mortality is on the rise and life expectancy is falling (The Scotsman,

2022; The Herald, 2022). While this is going on one nursing job in ten

is unfilled. People view nurses as the face of the NHS, and they see their NHS

as under threat.

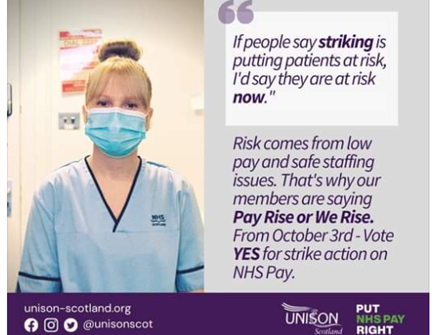

Source: TwitterIn a potential perfect storm for the Scottish

Government, with inflation breaking through the 10% barrier, nurses in Scotland

have been offered a pay rise of only 5% and to compound their self-created

problem the Scottish Government offered a flat percentage award to all staff meaning that senior

managers would get over four times the cash payment of nurses delivering direct

clinical care. A newly qualified registered nurse would see their salary

increase by just over £1,300 to just under £27,500

while the highest paid senior managers would receive an increase of almost

£5,500 to over £113,000. Scot's nurses 'sick of living on poverty line' gear up for strike action.

Source: TwitterIn a potential perfect storm for the Scottish

Government, with inflation breaking through the 10% barrier, nurses in Scotland

have been offered a pay rise of only 5% and to compound their self-created

problem the Scottish Government offered a flat percentage award to all staff meaning that senior

managers would get over four times the cash payment of nurses delivering direct

clinical care. A newly qualified registered nurse would see their salary

increase by just over £1,300 to just under £27,500

while the highest paid senior managers would receive an increase of almost

£5,500 to over £113,000. Scot's nurses 'sick of living on poverty line' gear up for strike action.The second

big change is that for the first time, following a change to their constitution

in 1995 to allow strike action (which their rules had not allowed previously),

the RCN are balloting for a strike meaning that all NHS nurses in trade unions

are being asked to take action.

The law regarding industrial action has changed significantly in the past 50 years: no longer is a simple show of hands enough to authorise such action at short notice. Strike action must go to a postal ballot and meet rigorous restrictions on time frames and notification to employers. The Trade Union Act of 2016 made action even harder. The Conservative Government’s legislation means that half of all members need to vote in any ballot to make any action legal as well having to get 40% of all members to vote in favour of action. Secondly, while the RCN now allows strike action, their constitution continues to hold that no official action will be authorised that is detrimental to the interests of patients. It remains to be seen how the RCN will balance that rule with a popular strike vote.

Nurses and other NHS workers on picket line duty, Glasgow Royal Infirmary, October 19, 2022 (with thanks to Tom Dickson for permission to use this film).

Concluding thoughts

Nursing remains an overwhelmingly female occupation with nine in ten Scottish nurses being women. Rightly or wrongly, it has been said nurses are less willing to take industrial action than other NHS workers and that part of this is due to the fact that nursing is predominantly a female profession. The fact that historically more action has been taken in psychiatric hospitals where the gender divide is not so large has been presented in support of this claim. Whatever the truth behind that claim there now appears to be a significant sea change in mood among nurses regardless of gender in support of industrial action. With nursing shortages as they are however it is unlikely any nursing strike in 2022/23 will have more than a symbolic effect unless patient care is impacted. The resolve of nurses to take action if no improved offer is made by the Scottish Government may very well soon be put to the test.

new.jpg)

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews