Find out more about The OU's Social Sciences qualifications.

Three African American women in Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance, ca. 1925

Three African American women in Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance, ca. 1925

This New York City neighbourhood - part of Manhattan borough - has long been home for its large proportion of African-American residents and businesses. After being associated for much of the twentieth century with crime and poverty, it is now experiencing social and economic gentrification.

As a settlement, it traces its routes back to the early Dutch pioneers - it's named for a Dutch city - and became part of the city of New York in 1873, after its value as an independent agricultural centre had declined.

The arrival of the elevated railroad seven years later brought a new rush of fortune to the area. A period of rapid property development followed, but an oversupply of new buildings and delays in the extension of the New York subway network sent prices into a downward spiral.

The low property prices proved attractive to emigre Eastern European Jews - something which caused consternation amongst landlords, who feared that the presence of so many recent arrivals would drive rents further down - a similar sentiment would be expressed later as African Americans moved into the neighbourhoods in larger numbers.

As early as 1880, there had been a black presence in Harlem, focused around 125th Street and West 130th Street. In 1904, though, another real estate crash and the worsening conditions of other black neighbourhoods led Philip Payton to create the Afro-American Realty Company. This business encouraged relocation for black families from areas around the Tenderloin, San Juan Hill and Hell's Kitchen - leaving behind areas which had been the focus of anti-black riots in the early years of the century - and for families whose homes were being demolished to make way for Penn Station. As the families moved in, so businesses and churches followed.

By 1920, central Harlem was predominantly black. By the 1930s, the black population was growing, fuelled by migration from the West Indies and the southern US. As more black people moved in, white residents left; between 1920 and 1930, 118,792 white people left the neighbourhood and 87,417 black people arrived. Some attempted to resist change in 'their' neighbourhood, entering into pacts to not sell or rent to black people; others attempted to buy property out from under black tenants - prompting the Afro-American Realty Company to reverse the process with properties from which it would evict white residents.

Rowhouse built for the African-American population of Harlem in the 1930s

Employment amongst black New Yorkers started to fall during the 1930s - and, with such a large black population, Harlem felt the effects of this strongly. Riots in Harlem in 1935 and 1943 made the situation worse - fear keeping away customers from the entertainment venues which had provided much employment. War brought a brief upturn in prospects, as war often will, but these new jobs vanished after the armistice and decline took hold once more.

Rowhouse built for the African-American population of Harlem in the 1930s

Employment amongst black New Yorkers started to fall during the 1930s - and, with such a large black population, Harlem felt the effects of this strongly. Riots in Harlem in 1935 and 1943 made the situation worse - fear keeping away customers from the entertainment venues which had provided much employment. War brought a brief upturn in prospects, as war often will, but these new jobs vanished after the armistice and decline took hold once more.

With New York's black population growing at a time when many city landlords would refuse black tenants, rents at Harlem rose faster than those in the city as whole, but precious little of this found its way into building maintenance - a 1950 census found that almost half of housing in Harlem was unsound. The high rents encouraged blockbusting, where speculators would buy one house in a block, renting to black tenants with much publicity and alarm amongst owners of neighbouring properties. These owners could often be relied upon to bail out quickly, allowing the blockbuster to acquire their properties cheaply; these, too, would be rented to black families.

With a relatively poor section of society being asked to pay relatively high rents, the consequence was a sardine-can like squeezing of people into buildings. While Manhattan in 2000 had a population density of 70,000 per square mile, Harlem in the mid 1920s crammed 215,000 souls into each square mile. It would only be the abandonment of buildings too expensive to keep habitable, or impossible to make a profit from while paying city fines and taxes, that would see density drop back to more normal levels in the 1970s. The outcome was municipality taking ownership of two-thirds of the real estate, and many empty blocks and buildings making the neighbourhood less attractive still to investors.

Cramped in, bitterly poor - generally, unemployment rates in Harlem would be double the general rate across New York - Harlem was an unhealthy place to live. A 1990 study suggested life expectancy for a 15-year-old female resident of Harlem would be roughly on a par with that of a 15-year-old girl living in India. She'd have about a 65% chance of surviving to 65 - while a black man would have about a 37% chance of making it to the same age, on a par with an Angolan male. As with other areas of deprivation and desperation, crime and drug abuse took a hold; at the same time, Harlem was the focus of a vibrant black culture and a strong religious life.

It also provided a focus for political activism, too - the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) became active in Harlem in 1910, rapidly becoming the largest chapter of the organisation, while Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association started campaigning from 1916. The Great Depression proved a rallying point - the Don't Buy Where You Can't Work campaign successfully forced shops to hire black employees in the 1920s; in the 1950s and 60s, rent strikes and pressure groups campaigned on housing, education and employment issues.

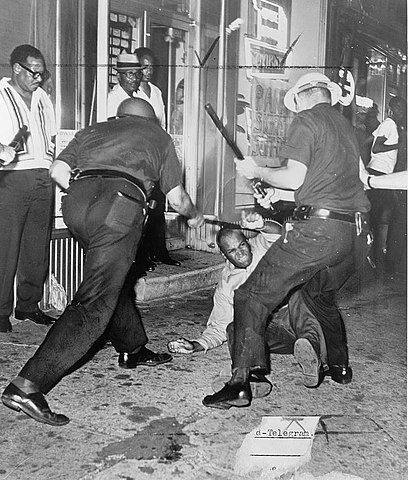

Harlem riots, 1964

The frustrations often found more violent outlets, too. In 1935 a (false) rumour that the police had killed a shoplifter sparked a riot which saw 600 stores looted and left three dead; in 1943, the shooting of a black soldier by a policeman caused a second outbreak of rioting - this time claiming six lives. The 1964 riots brought to a head tensions between locals and the NYPD - at the time, only one out of every seven cops in the district were black. Harlem was always an attractive recruiting ground for those beyond the mainstream of American politics - Communists were active in the 1930s; Malcolm X's Nation of Islam was just the highest-profile of dozens of black nationalist groups who found support or made their bases in the area and in 1966 The Black Panthers were organising in the neighbourhood.

Harlem riots, 1964

The frustrations often found more violent outlets, too. In 1935 a (false) rumour that the police had killed a shoplifter sparked a riot which saw 600 stores looted and left three dead; in 1943, the shooting of a black soldier by a policeman caused a second outbreak of rioting - this time claiming six lives. The 1964 riots brought to a head tensions between locals and the NYPD - at the time, only one out of every seven cops in the district were black. Harlem was always an attractive recruiting ground for those beyond the mainstream of American politics - Communists were active in the 1930s; Malcolm X's Nation of Islam was just the highest-profile of dozens of black nationalist groups who found support or made their bases in the area and in 1966 The Black Panthers were organising in the neighbourhood.

The 1970s were the bottom for Harlem - those who could afford to flee did; those who remained mainly did so not through choice, but because of lack of other options. Attempts by the City of New York to return confiscated properties to the market were quickly beset by scandal, fraud and allegations of profiteering without doing much to improve conditions for the general housing stock or those living in it.

Things improved in the late 1990s, as changes to federal and city policies drove down crime and focused redevelopment efforts on the retail corridor of 125th Street. The Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone channelled cash into the area from 1994; the area also was boosted as the forces gentrifying the rest of Manhattan and Brooklyn had completed much of their task and needed new areas to conquer with coffee bars and loft-style apartments. During the 90s, Central Harlem property values increased threefold, to the point where an empty shell could command a resale value of almost a million dollars.

But what of the future?

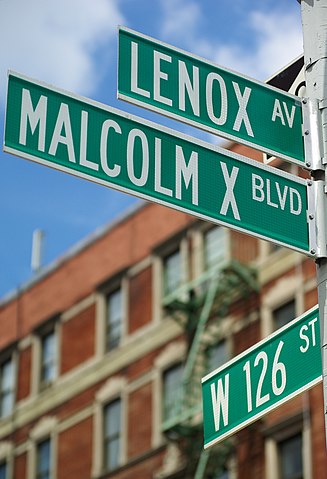

Street sign at corner of Malcolm X Boulevard and West 126th Street, Harlem, New York.

This brief history of Harlem, based on an edited version of the Wikipedia entry for Harlem, highlights the significance of the area for the African-American population of New York for more than a century.

Street sign at corner of Malcolm X Boulevard and West 126th Street, Harlem, New York.

This brief history of Harlem, based on an edited version of the Wikipedia entry for Harlem, highlights the significance of the area for the African-American population of New York for more than a century.

This has been an area where they have found a home and space of cultural and poltical empowerment, at the same time as being subject to very high levels of poverty, ill-health and unemployment. It is thus no surprise that the gentrification of Harlem over the last couple of decades has been highly contentious.

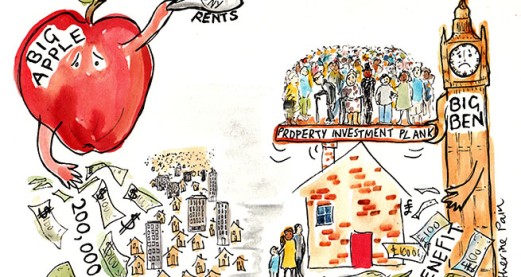

Gentrification is never a neutral process. Much of the academic literature on the subject has highlighted the ways in which processes of gentrification have forced low income households out of gentrifying neighborhoods as the middle class households move in, taking advantage of low housing costs and often architecturally appealing buildings.

Gentrification is thus argued to increase housing inequalities and disadvantage poorer households who cannot afford the rising prices and are thus displaced. In the case of Harlem this process has considerable impact on the African-American community for whom the locality has been home, as well as a site of empowerment in a sometimes hostile world.

Other writers focus on the advantages accruing to the middle class households who are able to buy relatively cheap housing and do it up to their own tastes, leaving in their wake a revitalised neighborhood of particular production and consumption patterns - the cappuccino café society - of a bourgeois bohemia. For others, gentrification is cast as the best way to revitalise inner cities, even if this causes the wholesale displacement of long established poorer communities.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews